The banana’s back. Not before time. Late last year, Lou Reed’s reputation suffered a serious blow when his ill-fated collaboration with Metallica met with hostility not witnessed since Metal Machine Music. He even had death threats. This 45th anniversary edition of The Velvet Underground & Nico is a timely reminder (if one is needed) that Reed at his best had few peers and no equals, and that his writer’s eye – literate, probing, explicit – was unflinching right from the start. He was always hardcore. Recorded when Reed was 24, The Velvet Underground & Nico drops us into a Manhattan drug deal (“I’m Waiting For The Man”), ushers us into a dark room where a girl in leather boots is whipping a kneeling man with a belt (“Venus In Furs”), and allows us to watch a syringe entering a human arm in real time (“Heroin”). Condemned in 1967 for breaking every taboo in the book, The Velvet Underground & Nico was a victim of wretched luck – mislaid master tapes, slashed budgets, negligible distribution – but stoically survived its punishing times like Beardless Harry riding the trolleys into Manhattan (“Run Run Run”). Then, like Van Gogh in early 20th century Europe, The Velvet Underground & Nico basked in posthumous recognition. It became a potent influence on David Bowie, Roxy Music, Bromley punks, Manchester post-punks, indie Glaswegians and hundreds – perhaps thousands – of others. Yet the album has always resisted attempts to imitate it. The music is too idiosyncratic to be anyone’s template. The songs’ atmospheres are too nuanced, too twisted – delicate paranoia (“Sunday Morning”), ice-cold tragedy (“All Tomorrow’s Parties”) – for another band to be capable of creating them. In Reed’s idea of people-watching, motives are complicated. Nobody is condemned for his or her predilection. The listener is credited with an open mind. And so, almost half a century later, The Velvet Underground & Nico still attracts quizzical visitors to its amoral museum. Universal’s 6CD boxset is by far the most in-depth reissue the album has ever had. Newly remastered throughout, it contains stereo and mono versions, original singles, alternate takes, different mixes and an entire Nico LP (Chelsea Girl). Major incentives appear on disc four with the official release of two VU bootlegs: a 30-minute rehearsal at The Factory in January 1966, and engineer Norman Dolph’s acetate of the Scepter Studios sessions in April, which formed the basis of the album. Discs five and six offer 94 minutes from a November 1966 concert in Columbus, Ohio (with Nico in the line-up), bootlegged during the ’80s on the LPs 1966 and Down For You Is Up. Thus a fan of “All Tomorrow’s Parties”, for example, can hear it seven times: the traditional double-voiced version in stereo, the same in mono, the alternative single-voiced version, an instrumental version, an edited mono 45, a Scepter Studios mix and a live recording. Most of the boxset takes place in mono, so we need to understand right away that the difference between stereo and mono, for the Velvets, was stark. A good illustration is what happens to “European Son”. The song is amazing by any standards, a frantic, chugging, dissonant drone with a mad banjo-like guitar making avant-garde use of feedback. In stereo, it’s as heart-stopping a rollercoaster as the Velvets ever took us on. But in mono, the walls narrow and the claustrophobia kicks in. Crank it loud and it’s a bass-heavy rumble punctuated by ear-splitting screams. We can’t hear Mo Tucker’s drums, so we lose the beat and feel disorientated. It’s a very uncomfortable sensation. The same happens on the mono “Heroin” when John Cale’s viola suddenly monopolises the air space like a demented Paganini, reducing Tucker to a faraway muffled thump as if she’s banging a broomstick on a ceiling three floors below. In essence, stereo gave the Velvets width – but mono gives them violence. The white noise cacophonies border on sadism; they really must have wanted to frighten the life out of people. The Factory rehearsal in January 1966 and the Scepter sessions in April reveal a few insights into how certain arrangements took shape. In January, Nico was being considered for “There She Goes Again”, a decision that was later changed. “Venus In Furs” was still a work-in-progress, with Reed dictating the lyrics (“comes... in bells...”) to an onlooker while someone off-mic sang Bo Diddley’s “Crackin’ Up” to the guitar chords. Cale’s viola was evilly prominent on “Heroin” and Tucker kept time with a tambourine. By April at Scepter, Reed’s voice was adopting a snarl on “Heroin”, far removed from the woozy-sounding character he’d inhabit on the final version, but at least Tucker was now pounding her drums. And “Venus In Furs” had structure, even if Reed sang it with none of the sinister dreaminess of the May re-recording. Captured live by a fan in November, the Velvets were ‘promoting’ an album that their label MGM-Verve had frustratingly not yet released. The tape is old and beset by dropouts and general wear-and-tear, but it’s striking how faithful the Velvets are to their beloved ballads (“All Tomorrow’s Parties”, “Femme Fatale”) and even to some of the heavier material (“Run Run Run”, “The Black Angel’s Death Song”). They play them as if they’re proud of them, which is the best way to play them. The true chaos is reserved for a pair of mammoth improvisations, “Melody Laughter” and “The Nothing Song”, which bookend the concert in shrieking feedback and ominous drones. Though its intensity can intimidate, The Velvet Underground & Nico was clearly made in a spirit of fun. It’s often forgotten that Reed laughs several times on the album, and we can imagine the grin on Cale’s face, too, as he hammers away at his piano on “I’m Waiting For The Man”. They moved from dispassionate reportage to touching tenderness, from a “whiplash girl-child” to a poor Cinderella in dowdy clothes. They reconvened in April 1967 (minus Tucker) to record Nico’s fine solo LP Chelsea Girl, by which time journalists and DJs were telling them, to their dismay, that their banana was rotten. David Cavanagh

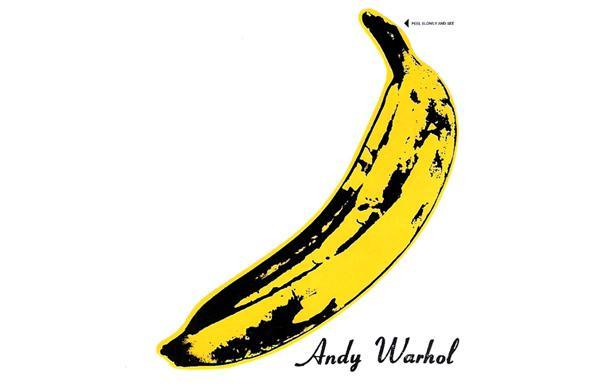

The banana’s back. Not before time. Late last year, Lou Reed’s reputation suffered a serious blow when his ill-fated collaboration with Metallica met with hostility not witnessed since Metal Machine Music. He even had death threats. This 45th anniversary edition of The Velvet Underground & Nico is a timely reminder (if one is needed) that Reed at his best had few peers and no equals, and that his writer’s eye – literate, probing, explicit – was unflinching right from the start. He was always hardcore.

Recorded when Reed was 24, The Velvet Underground & Nico drops us into a Manhattan drug deal (“I’m Waiting For The Man”), ushers us into a dark room where a girl in leather boots is whipping a kneeling man with a belt (“Venus In Furs”), and allows us to watch a syringe entering a human arm in real time (“Heroin”). Condemned in 1967 for breaking every taboo in the book, The Velvet Underground & Nico was a victim of wretched luck – mislaid master tapes, slashed budgets, negligible distribution – but stoically survived its punishing times like Beardless Harry riding the trolleys into Manhattan (“Run Run Run”). Then, like Van Gogh in early 20th century Europe, The Velvet Underground & Nico basked in posthumous recognition. It became a potent influence on David Bowie, Roxy Music, Bromley punks, Manchester post-punks, indie Glaswegians and hundreds – perhaps thousands – of others. Yet the album has always resisted attempts to imitate it. The music is too idiosyncratic to be anyone’s template. The songs’ atmospheres are too nuanced, too twisted – delicate paranoia (“Sunday Morning”), ice-cold tragedy (“All Tomorrow’s Parties”) – for another band to be capable of creating them. In Reed’s idea of people-watching, motives are complicated. Nobody is condemned for his or her predilection. The listener is credited with an open mind. And so, almost half a century later, The Velvet Underground & Nico still attracts quizzical visitors to its amoral museum.

Universal’s 6CD boxset is by far the most in-depth reissue the album has ever had. Newly remastered throughout, it contains stereo and mono versions, original singles, alternate takes, different mixes and an entire Nico LP (Chelsea Girl). Major incentives appear on disc four with the official release of two VU bootlegs: a 30-minute rehearsal at The Factory in January 1966, and engineer Norman Dolph’s acetate of the Scepter Studios sessions in April, which formed the basis of the album. Discs five and six offer 94 minutes from a November 1966 concert in Columbus, Ohio (with Nico in the line-up), bootlegged during the ’80s on the LPs 1966 and Down For You Is Up. Thus a fan of “All Tomorrow’s Parties”, for example, can hear it seven times: the traditional double-voiced version in stereo, the same in mono, the alternative single-voiced version, an instrumental version, an edited mono 45, a Scepter Studios mix and a live recording.

Most of the boxset takes place in mono, so we need to understand right away that the difference between stereo and mono, for the Velvets, was stark. A good illustration is what happens to “European Son”. The song is amazing by any standards, a frantic, chugging, dissonant drone with a mad banjo-like guitar making avant-garde use of feedback. In stereo, it’s as heart-stopping a rollercoaster as the Velvets ever took us on. But in mono, the walls narrow and the claustrophobia kicks in. Crank it loud and it’s a bass-heavy rumble punctuated by ear-splitting screams. We can’t hear Mo Tucker’s drums, so we lose the beat and feel disorientated. It’s a very uncomfortable sensation. The same happens on the mono “Heroin” when John Cale’s viola suddenly monopolises the air space like a demented Paganini, reducing Tucker to a faraway muffled thump as if she’s banging a broomstick on a ceiling three floors below. In essence, stereo gave the Velvets width – but mono gives them violence. The white noise cacophonies border on sadism; they really must have wanted to frighten the life out of people.

The Factory rehearsal in January 1966 and the Scepter sessions in April reveal a few insights into how certain arrangements took shape. In January, Nico was being considered for “There She Goes Again”, a decision that was later changed. “Venus In Furs” was still a work-in-progress, with Reed dictating the lyrics (“comes… in bells…”) to an onlooker while someone off-mic sang Bo Diddley’s “Crackin’ Up” to the guitar chords. Cale’s viola was evilly prominent on “Heroin” and Tucker kept time with a tambourine. By April at Scepter, Reed’s voice was adopting a snarl on “Heroin”, far removed from the woozy-sounding character he’d inhabit on the final version, but at least Tucker was now pounding her drums. And “Venus In Furs” had structure, even if Reed sang it with none of the sinister dreaminess of the May re-recording.

Captured live by a fan in November, the Velvets were ‘promoting’ an album that their label MGM-Verve had frustratingly not yet released. The tape is old and beset by dropouts and general wear-and-tear, but it’s striking how faithful the Velvets are to their beloved ballads (“All Tomorrow’s Parties”, “Femme Fatale”) and even to some of the heavier material (“Run Run Run”, “The Black Angel’s Death Song”). They play them as if they’re proud of them, which is the best way to play them. The true chaos is reserved for a pair of mammoth improvisations, “Melody Laughter” and “The Nothing Song”, which bookend the concert in shrieking feedback and ominous drones.

Though its intensity can intimidate, The Velvet Underground & Nico was clearly made in a spirit of fun. It’s often forgotten that Reed laughs several times on the album, and we can imagine the grin on Cale’s face, too, as he hammers away at his piano on “I’m Waiting For The Man”. They moved from dispassionate reportage to touching tenderness, from a “whiplash girl-child” to a poor Cinderella in dowdy clothes. They reconvened in April 1967 (minus Tucker) to record Nico’s fine solo LP Chelsea Girl, by which time journalists and DJs were telling them, to their dismay, that their banana was rotten.

David Cavanagh