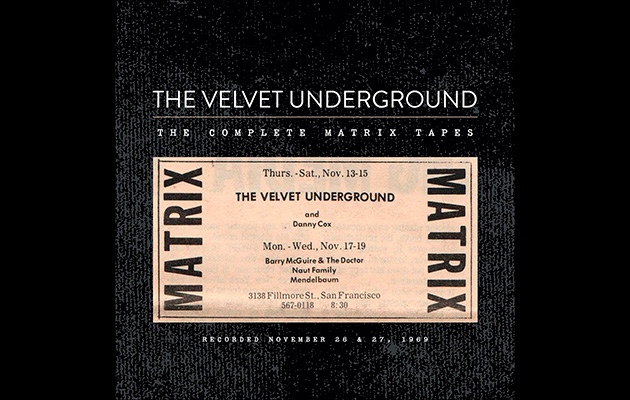

When The Velvet Underground played San Francisco’s intimate, musician-friendly club The Matrix in late November/early December 1969, things were changing both for the band and for the city’s music scene. The Velvets were no longer the raging wild beast they had been during John Cale’s tenure: a deliberate shift pop-wards had resulted in their third album, released earlier that year, surprising fans with its folksy understatement and uncharacteristically sentimental attitudes; and they were preparing material for another album, their first for Atlantic, hopefully following the new label’s demand for a record “loaded with hits”.

San Francisco’s music scene, meanwhile, was still registering the queasy aftershock of the Manson Family Murders down the coast in Los Angeles. Most bands had already left the city, escaping to Marin County to avoid the huge influx of panhandling hippies and rubbernecking gawkers into the Haight Ashbury district. And a distinct shift in musical style had been signalled by the colossal success that year of local band Creedence Clearwater Revival, whose short, snappy little songs had scored them a run of hits through 1969 that included “Proud Mary”, “Bad Moon Rising”, “Green River” and “Fortunate Son”. The Velvets might have been forgiven for thinking that their new, neatened-up, pop-conscious approach would chime nicely with the changing conditions: was it really that far, after all, from “Proud Mary” to “Sweet Jane”?

All the same, they opted to open their shows with the old warhorse “I’m Waiting For The Man”, an echo of their earlier, darker inclinations. “It’s going to be a very serious rock’n’roll set,” Lou Reed teased the audience amiably. “I don’t want any of you to enjoy yourselves frivolously, because it goes against national policy. This is a song written under the influence of dreams, and it’s about one man’s journey from uptown to downtown.” What follows is a very different version from the urgent, implacable motorik of the first Velvets album: a slow, languid affair sauntering past the 10-minute mark on the string-bending swoons of limpid guitars, while Reed affects the casual, laissez-faire cool of a nightclub crooner. It’s bizarrely devoid of impact, almost trance-like, as if the song has been strained through the aesthetic of the third album; and not for the first time during their shows at the venue, it’s greeted initially with stunned silence, followed by a desultory smattering of applause.

It’s a red herring, in a sense, as thereafter the shows develop an itchy momentum through nippy rockers like “What Goes On”, “There She Goes Again” and “We’re Gonna Have A Real Good Time Together”, built on Sterling Morrison’s frantic, choppy rhythm guitar, so feverish it almost trips over itself, and Mo Tucker’s forceful, take-no-prisoners snare shots. Reed’s guitar and Doug Yule’s organ, when called upon to solo, pursue small figures incessantly: compared to the expansive, freewheeling improvs the Matrix audience might be familiar with courtesy of such as the Dead and Quicksilver, the Velvets here are rudimentary and tight, disciplined rather than indulgent, and their performances hum with the new, minimalist aesthetic then developing a significant influence in New York art circles.

“I Can’t Stand It” is another itchy, rhythmic piece that finds the band in transition en route to Loaded, with Reed’s surreal, Dylanesque lines (“I live with thirteen dead cats/A purple dog that wears spats/They’re all living in the hall/And I can’t stand it any more”) offering few semantic clues. But there’s still room within the tight, itchy groove for Reed to essay an odd, modal guitar solo, through which his Ornette Coleman influence shines with a dark, confrontational gleam. You can sense the effect it’s having on the band’s chum Robert Quine, out in the crowd with his trusty cassette recorder, capturing it all for posterity. In a few years’ time, Quine will apply these lessons in his own “skronk” guitar stylings for Richard Hell & The Voidoids, and for Reed himself.

Sometimes, they try a bit too hard, as when Reed yelps as he launches into his solo in “Sweet Bonnie Brown/Too Much”, a pair of throwaway rockabilly-style songs featuring notably dull lyrics, about which his bandmates can barely hide the contempt in their desultory chorus responses. And two runs through “White Light/White Heat” are loose and raggedy, paradoxically rushed but stretched-out, the closest they come to losing their shape apart from the woefully wallowy “Ocean”, which features some of the world’s dullest organ soloing, and simply fails to command attention.

At other times, they are simply perverse, with a grim, antagonistic “Black Angel’s Death Song” all too accurately summarised by Reed’s smirking introduction: “This song we haven’t played in a really long time, because it used to empty clubs – as a matter of fact, when a club wanted to close for a while it would get in touch with us to play this song”. But overall, there’s a good balance throughout the sets between innocence and experience, fast and slow, benign and malign. The four versions of “Heroin” have a mesmerising, queasy grace, and the two lashes of “Venus In Furs” are stately, majestic, dark and velveteen, like a high-class hooker’s counterpane. The four versions of “Some Kinda Love” have a nodding, hypnotic momentum, with Reed again playing the worldly crooner; and there’s a lovely formal, faded glamour to “Pale Blue Eyes” that balances beautifully with the sweetness of the ensuing “After Hours”.

Substantial tranches of the Matrix Tapes have already appeared elsewhere, firstly in 1974 on the 1969: The Velvet Underground Live double album, and subsequently on 2001’s Bootleg Series Volume 1: The Quine Tapes. More recently, Matrix recordings comprised two of the six discs of the 45th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition of the Velvets’ third album, including the 37-minute version of “Sister Ray” included here, which offers the clearest indication of how the band had changed since the departure of John Cale. Starting out slow and relaxed, speeding up, then dropping back and surging forward periodically, it grooves along like a standard jam session. But it’s a far more measured acceleration and development than on the 1967 Gymnasium live recording included on the White Light/White Heat 45th Anniversary Edition: there’s none of the original’s architectonic quality, that sense of musical plates shifting under forces beyond their control. Those days were well and truly gone – and soon, so would Lou Reed himself.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.