Remastered with bonus tracks. Weller and co's fourth album improves with age... There is still a widely-held perception that Jam albums follow a numerical pattern; an inverse of the Star Trek Movie Curse. That is, the odd-numbered Jam albums are excellent, while the even-numbered ones are... well… not. This has always affected the reputation of The Jam’s fourth album, with its healthy sales and inclusion of breakthrough Top 3 single “The Eton Rifles” undercut by a half-finished concept and a dodgy cover version closer that inevitably leads to Setting Sons feeling rushed and inconclusive. But comparing Setting Sons with, say, the frankly awful second album This Is The Modern World is pushing a nerdy fan theory way too far. The excellence of six of its ten songs, and the tougher, denser sound fashioned by loyal Jam producer Vic Coppersmith-Heaven, make Setting Sons the successful link between the creative breakthrough of 1978’s career-saving All Mod Cons and the February 1980 triumph of the “Going Underground” single, an anthem of nuclear panic and social alienation that revealed that The Jam had stealthily climbed to biggest-band-in-Britain status by becoming the first single to enter the UK charts at No.1 since 1973. The bonus tracks added to this remastered version – the brilliant pre-album singles and B-sides, the work-in-progress Setting Sons demos including three previously unreleased songs, the final Peel sessions, and the vinyl-only “Live In Brighton 1979” set – give the Jam loyalist an overview of exactly how Paul Weller, Bruce Foxton and Rick Buckler made that creative leap at the end of a decade that had began with the Beatles’ split and ended with the anti-rock experiments of post-punk. Setting Sons saw Weller basing more of his lyrics on his own poetry, and established his credentials as an ironic commentator on both the British class system and the fleeting bonds of childhood friendship. The typically tough-but-tuneful “Thick As Thieves” and “Burning Sky”, and the ambitious mini-rock operatic “Little Boy Soldiers” are the most explicit survivors of the original album concept (as revealed to NME’s Nick Kent in September), of three male friends torn apart by a British civil war who meet up again after the war’s conclusion. But “Private Hell”, “Wasteland”, “Saturday’s Kids”, “The Eton Rifles” and the orchestral version of Bruce Foxton’s “Smithers-Jones” are all close relations; bitter reflections on ordinary English men and women – working-class and suburban middle-class – alienated and manipulated by corporate and military power. Only the closing “Heatwave” – essentially a cover of The Who’s cover of the Martha Reeves And The Vandellas hit, featuring future Style Councillor Mick Talbot’s first keyboard work with Weller - and the hilarious, out-of-character opener “Girl On The Phone” break ranks. One of the most underrated Weller gems, the latter examines the power of an imaginary stalker who knows everything about our bemused boy wonder, even “the size of my cock!” It’s the first evidence of Weller’s dark humour. The new remaster gives freer rein to the density of the sound Vic Smith gradually developed for The Jam, with Foxton’s bass punching through, revealing just how much space his busy, lyrical lines open up for Weller to use guitar as sound effect rather than straight rhythm and lead. And while the Brighton live show is inessential, two of the three newly unearthed songs, Weller’s “Simon” and “Along The Grove”, are stark, caustic and could have been contenders. Foxton’s “Best Of Both Worlds” may have been best left in the vaults. But Setting Sons has improved with age. It reminds us that working class life was best captured, not by The Clash, nor PiL, nor even The Specials, but by the mock celebration of The Jam’s “Saturday’s Kids”, with its life of “insults”, beer and “half-time results”, and Weller’s recognition that we – and our parents, with their “wallpaper lives” – were “the real creatures that time has forgot”. At the time we were stunned, and grateful, that any dapper young rock ‘n’ roll star had noticed. The insight and empathy shown here marked Weller out as the first pop hero of the coming decade. Garry Mulholland Q&A Paul Weller What do you think of Setting Sons now? Where does it sit among the Jam albums for you? Sound Affects is my favourite. That was us doing something really different. But I think there’s some great songs on Setting Sons, with “The Eton Rifles” as the stand-out. “Private Hell” I really like as well. I was concentrating more on my lyrics at that time, and quite a few of the songs, like “Burning Sky”, started off as prose or poetry. How did you start writing like that? “Down At The Tube Station…” from All Mod Cons was a long poem which Vic Smith helped me shape into a song, and that convinced me that there were ways of making things a bit more literary and still fitting them into a song structure. My songs were getting a bit more involved than verse-chorus-verse-chorus. So, from a selfish point of view, I felt I made a leap forward with my writing on Setting Sons. Do you agree in hindsight that “Heatwave” was out-of-place? Yeah, totally! It’s the “Yellow Submarine” of Setting Sons, innit? But I didn’t have any more songs… that’s the truth of the matter. It’s a shame there isn’t a real closer for the album, but that’s just the way it was. Why did you abandon the friends-reunite-after-civil-war concept? I think I just ran out of ideas, if I’m really honest. Maybe I wasn’t sure if it was the right thing for us to do anyway. It was a bit of a half-baked concept. Was “Girl On The Phone” about a real female stalker? Our fans were pretty obsessive but not to that extent! That song came from sitting in our offices in Shepherds Bush with an acoustic guitar because we needed two more songs for the album. I just knocked out “Girl On The Phone” and “Private Hell”. The title is from a Roy Lichtenstein pop art painting called Girl On The Phone. Sorry if I’ve ruined it for you! INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND Uncut is available as a digital edition! Download here on your iPad/iPhone and here on your Kindle Fire or Nook.

Remastered with bonus tracks. Weller and co’s fourth album improves with age…

There is still a widely-held perception that Jam albums follow a numerical pattern; an inverse of the Star Trek Movie Curse. That is, the odd-numbered Jam albums are excellent, while the even-numbered ones are… well… not.

This has always affected the reputation of The Jam’s fourth album, with its healthy sales and inclusion of breakthrough Top 3 single “The Eton Rifles” undercut by a half-finished concept and a dodgy cover version closer that inevitably leads to Setting Sons feeling rushed and inconclusive.

But comparing Setting Sons with, say, the frankly awful second album This Is The Modern World is pushing a nerdy fan theory way too far. The excellence of six of its ten songs, and the tougher, denser sound fashioned by loyal Jam producer Vic Coppersmith-Heaven, make Setting Sons the successful link between the creative breakthrough of 1978’s career-saving All Mod Cons and the February 1980 triumph of the “Going Underground” single, an anthem of nuclear panic and social alienation that revealed that The Jam had stealthily climbed to biggest-band-in-Britain status by becoming the first single to enter the UK charts at No.1 since 1973.

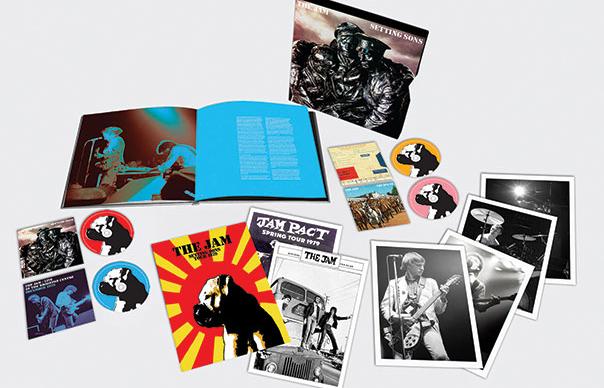

The bonus tracks added to this remastered version – the brilliant pre-album singles and B-sides, the work-in-progress Setting Sons demos including three previously unreleased songs, the final Peel sessions, and the vinyl-only “Live In Brighton 1979” set – give the Jam loyalist an overview of exactly how Paul Weller, Bruce Foxton and Rick Buckler made that creative leap at the end of a decade that had began with the Beatles’ split and ended with the anti-rock experiments of post-punk.

Setting Sons saw Weller basing more of his lyrics on his own poetry, and established his credentials as an ironic commentator on both the British class system and the fleeting bonds of childhood friendship. The typically tough-but-tuneful “Thick As Thieves” and “Burning Sky”, and the ambitious mini-rock operatic “Little Boy Soldiers” are the most explicit survivors of the original album concept (as revealed to NME’s Nick Kent in September), of three male friends torn apart by a British civil war who meet up again after the war’s conclusion.

But “Private Hell”, “Wasteland”, “Saturday’s Kids”, “The Eton Rifles” and the orchestral version of Bruce Foxton’s “Smithers-Jones” are all close relations; bitter reflections on ordinary English men and women – working-class and suburban middle-class – alienated and manipulated by corporate and military power.

Only the closing “Heatwave” – essentially a cover of The Who’s cover of the Martha Reeves And The Vandellas hit, featuring future Style Councillor Mick Talbot’s first keyboard work with Weller – and the hilarious, out-of-character opener “Girl On The Phone” break ranks. One of the most underrated Weller gems, the latter examines the power of an imaginary stalker who knows everything about our bemused boy wonder, even “the size of my cock!” It’s the first evidence of Weller’s dark humour.

The new remaster gives freer rein to the density of the sound Vic Smith gradually developed for The Jam, with Foxton’s bass punching through, revealing just how much space his busy, lyrical lines open up for Weller to use guitar as sound effect rather than straight rhythm and lead. And while the Brighton live show is inessential, two of the three newly unearthed songs, Weller’s “Simon” and “Along The Grove”, are stark, caustic and could have been contenders. Foxton’s “Best Of Both Worlds” may have been best left in the vaults.

But Setting Sons has improved with age. It reminds us that working class life was best captured, not by The Clash, nor PiL, nor even The Specials, but by the mock celebration of The Jam’s “Saturday’s Kids”, with its life of “insults”, beer and “half-time results”, and Weller’s recognition that we – and our parents, with their “wallpaper lives” – were “the real creatures that time has forgot”.

At the time we were stunned, and grateful, that any dapper young rock ‘n’ roll star had noticed. The insight and empathy shown here marked Weller out as the first pop hero of the coming decade.

Garry Mulholland

Q&A

Paul Weller

What do you think of Setting Sons now? Where does it sit among the Jam albums for you?

Sound Affects is my favourite. That was us doing something really different. But I think there’s some great songs on Setting Sons, with “The Eton Rifles” as the stand-out. “Private Hell” I really like as well. I was concentrating more on my lyrics at that time, and quite a few of the songs, like “Burning Sky”, started off as prose or poetry.

How did you start writing like that?

“Down At The Tube Station…” from All Mod Cons was a long poem which Vic Smith helped me shape into a song, and that convinced me that there were ways of making things a bit more literary and still fitting them into a song structure. My songs were getting a bit more involved than verse-chorus-verse-chorus. So, from a selfish point of view, I felt I made a leap forward with my writing on Setting Sons.

Do you agree in hindsight that “Heatwave” was out-of-place?

Yeah, totally! It’s the “Yellow Submarine” of Setting Sons, innit? But I didn’t have any more songs… that’s the truth of the matter. It’s a shame there isn’t a real closer for the album, but that’s just the way it was.

Why did you abandon the friends-reunite-after-civil-war concept?

I think I just ran out of ideas, if I’m really honest. Maybe I wasn’t sure if it was the right thing for us to do anyway. It was a bit of a half-baked concept.

Was “Girl On The Phone” about a real female stalker?

Our fans were pretty obsessive but not to that extent! That song came from sitting in our offices in Shepherds Bush with an acoustic guitar because we needed two more songs for the album. I just knocked out “Girl On The Phone” and “Private Hell”. The title is from a Roy Lichtenstein pop art painting called Girl On The Phone. Sorry if I’ve ruined it for you!

INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND

Uncut is available as a digital edition! Download here on your iPad/iPhone and here on your Kindle Fire or Nook.