At 86 (87 on September 7), the great tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins is the elder statesman among the survivors from jazz’s heroic age. They’re even talking about renaming the Williamsburg Bridge after him, in recognition of a famous sabbatical from public performance in the 1950s during which he searched for new musical solutions while playing alone on the windswept walkway, high above the East River, of the structure connecting Lower Manhattan with the district of Brooklyn from which it takes its present name.

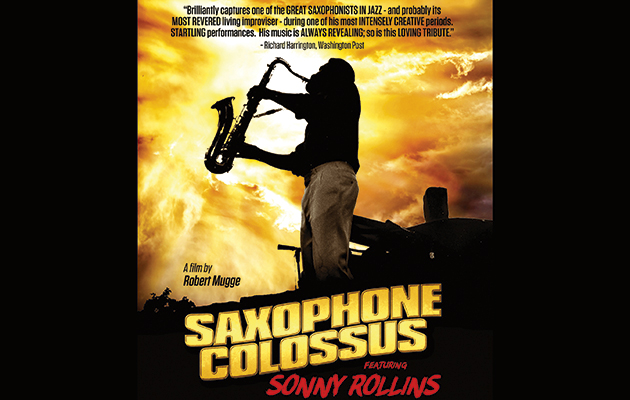

Rollins’ return to action in 1959, when he felt ready to meet the challenge posed by the emergence of John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, is mentioned in Robert Mugge’s documentary, a time capsule dominated by two performances from 1986, the year in which the film was made. Mugge begins and ends with extracts from an open-air performance at a sort of jazz picnic in the Saugerties, in upstate New York. Fronting his regular band of the time, Rollins unfurls extended improvs that show him at his most compelling and his most troublesome: tired rhetorical motifs investigated to the point of exhaustion alternate with brief bursts of astonishing invention.

The musical core of the film, however, is the performance in a Tokyo hall of the specially commissioned Concerto For Tenor Saxophone And Orchestra, on which he collaborated with the Finnish jazz composer Heikki Sarmanto. Sonny with strings turns out to be unfailingly pleasant and sometimes a little more than that, provoking the featured soloist to passages of concentrated lyricism, but it failed to establish a significant place in his large body of work. There are a couple of interviews with Rollins, filmed in New York and Tokyo; at one point he says that he is “closer to my saxophone than to Lucille” – his wife, who is sitting next to him.

We also hear thoughtful assessments from the critics Ira Gitler, Gary Giddins and Francis Davis, who pinpoints a reason why Rollins, although an acknowledged master, has not commanded the same degree of devotion as Coltrane or Coleman: “He never formed a band in his own image… And in a way that almost enhances his appeal, that lack of context. Sonny Rollins is the single most excellent standard of jazz you can possibly imagine.” But to appreciate that standard to the full, you would need to go back to something like the 1957 Blue Note recordings from the Village Vanguard, which is to say before the emergence of rivals chipped away at the young giant’s seemingly ironclad self-confidence, undermining his sense of his own place in the modern world he’d helped create.

EXTRAS: 6/10. Updated commentary by director Robert Mugge.