In 1821, Thomas De Quincey compared opium addiction to being trapped in a “castle of indolence”. An opium eater, he wrote, “lies under the weight of incubus and nightmare… He would lay down his life if he might but get up and walk; but he is powerless as an infant, and cannot even attempt to rise.” Forgive the pretension, it’s just that Rufus Wainwright drives you to these sort of lofty references. Release The Stars, as Wainwright tells Uncut on the next page, was recorded in a state of extreme purity, the lavish drug binges long behind him. It’s not so easy, though, to escape that castle of indolence. For nearly a decade now, Wainwright has proved himself to be one of the most gifted songwriters in America. His erudition, wit and general gayness have been so pronounced, we’re technically obliged to call him Wildean at every opportunity. He has a magical way of joining the dots between Cole Porter and Thom Yorke, between David Ackles and Jeff Buckley. He’s a serious artist, though one with a keen sense of his own absurdity: the cover of 2005’s Want Two found Wainwright posing as a Pre-Raphaelite Ophelia, all dressed up and ready to drown. Still, it is his voice, so extravagantly mournful, so luxuriously torpid, that suggests he must always remain The Jaded Bohemian, even without the drugs. Release The Stars, his fifth and possibly best album, should be the record where he escapes such stereotypes. But curiously, he sounds more opulently wasted than ever, as if he’s realised that ennui, in the right hands, can be a creative attribute rather than a professional curse. “Going To A Town” might be the angriest lyric Wainwright has written, an indictment of the country of his birth that hinges on the refrain, “I’m so tired of you America”. That “tired” is the key, though: rarely has a protest song been so dolorous. Like De Quincey, he’d start a revolution if he could only get off the chaise longue. The effect is striking, not least because “Going To A Town” sounds something like Radiohead’s “High And Dry” rescored as a torch song. Release The Stars is full of lovely tunes, but it’s the imagination with which Wainwright tackles them that raises this album above his previous work. While Want One and Want Two were slightly marred by a glossy pop finish, Release The Stars has a wood-panelled classiness, and arrangements whose complexity augments the tunes rather than overwhelms them. Neil Tennant is listed as Executive Producer, but it’s Wainwright himself who actually produced these 12 songs, and who navigated his own path from studio to studio, picking up an ever-more bejewelled coterie of musicians along the way. If the vocal tone might often be one of somnambulence, the practicalities of making Release The Stars suggest a very clear head. The castlist includes regulars like sister Martha, mother Kate McGarrigle and Teddy Thompson, venerable actress Sîan Phillips, Tennant on synths, sundry orchestras plus, on lead guitar, Teddy’s father Richard Thompson. Fortunately, Wainwright is adept at finding grace and space where others would be swamped. The opening “Do I Disappoint You” sees him present a withering defence of his own human frailties, while one orchestral battalion after another mount their attacks and Martha Wainwright (a much stronger singer than her brother, by the by) summons “CHAOS!” and “DESTRUCTION!” like a marauding Fury. The title track, meanwhile, has a brassy Broadway swagger – the result, presumably, of Wainwright immersing himself in that world for his Judy Garland tribute concerts (the song’s lyrical inspiration comes from Lorca Cohen, Leonard’s daughter, missing the New York show). Wainwright, though, is not a belter, and it’s his unsuitability to the top hat and high-kicking routine that makes this grand, flawed finale so compelling. “Slideshow” is even better, a masterpiece of wry emotional dithering that begins, pointedly, “Do I love you because you treat me so indifferently?/ Or is it the medication?” Pursued by 14 musicians and the London Session Orchestra, he moves at a languid pace through a sequence of euphoric crescendos until, after four minutes, Richard Thompson cuts through the melodrama with a clean, needling solo and Wainwright is left in a lucid reverie, realising, “Do I love you? Yes I do.” It’s a rare moment of resolution on an album filled with romantic indecision, with dreams of travel and leave-taking. “Between My Legs” is sprightly and uncharacteristically rocking, describing a dysfunctional relationship that can only be consummated with an escape from the city. There are apocalyptic overtones, too, as Wainwright describes a frenzied mass evacuation, then employs Sîan Phillips to incant his words like a spell over another ravishing climax. If these set pieces initially grab the attention, Release The Stars has other pleasures that reveal themselves more discreetly. “Leaving For Paris” is an end-of-the-affair piano ballad which intimates that Wainwright’s finest work may yet be solemn and minimal. There’s a baroque, Brel-like trinket called “Tulsa” that claims Brandon Flowers “tastes of potato chips in the morning”. And finally, amid all the gilt, theatre, recherché poses and brilliant music, there’s a hint that, without the drugs, the castle of indolence might not always be a rewarding place to hang out. “I’m tired of writing elegies to boredom,” he sings in “Sanssouci”, “I just want to be at Sanssouci tonight.” “Sans souci” translates as carefree and, of course, the promise of happiness – “the boys that made me lose the blues” – turns out to be an illusion. When Wainwright arrives at the club it is deserted, and, terminally world-weary, he can only retreat to his melancholy boudoir. If he keeps making albums as good as this, we should wall him up in there forever. JOHN MULVEY

In 1821, Thomas De Quincey compared opium addiction to being trapped in a “castle of indolence”. An opium eater, he wrote, “lies under the weight of incubus and nightmare… He would lay down his life if he might but get up and walk; but he is powerless as an infant, and cannot even attempt to rise.”

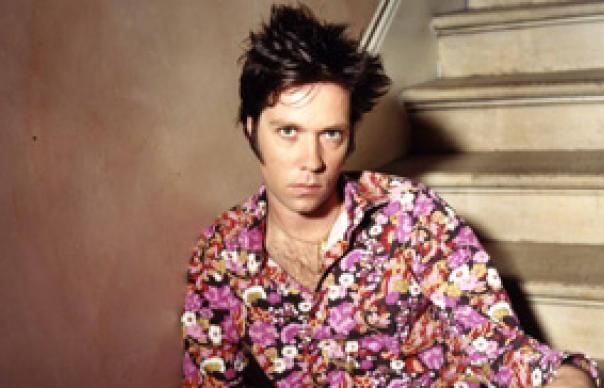

Forgive the pretension, it’s just that Rufus Wainwright drives you to these sort of lofty references. Release The Stars, as Wainwright tells Uncut on the next page, was recorded in a state of extreme purity, the lavish drug binges long behind him. It’s not so easy, though, to escape that castle of indolence.

For nearly a decade now, Wainwright has proved himself to be one of the most gifted songwriters in America. His erudition, wit and general gayness have been so pronounced, we’re technically obliged to call him Wildean at every opportunity. He has a magical way of joining the dots between Cole Porter and Thom Yorke, between David Ackles and Jeff Buckley. He’s a serious artist, though one with a keen sense of his own absurdity: the cover of 2005’s Want Two found Wainwright posing as a Pre-Raphaelite Ophelia, all dressed up and ready to drown.

Still, it is his voice, so extravagantly mournful, so luxuriously torpid, that suggests he must always remain The Jaded Bohemian, even without the drugs. Release The Stars, his fifth and possibly best album, should be the record where he escapes such stereotypes. But curiously, he sounds more opulently wasted than ever, as if he’s realised that ennui, in the right hands, can be a creative attribute rather than a professional curse. “Going To A Town” might be the angriest lyric Wainwright has written, an indictment of the country of his birth that hinges on the refrain, “I’m so tired of you America”. That “tired” is the key, though: rarely has a protest song been so dolorous. Like De Quincey, he’d start a revolution if he could only get off the chaise longue.

The effect is striking, not least because “Going To A Town” sounds something like Radiohead’s “High And Dry” rescored as a torch song. Release The Stars is full of lovely tunes, but it’s the imagination with which Wainwright tackles them that raises this album above his previous work. While Want One and Want Two were slightly marred by a glossy pop finish, Release The Stars has a wood-panelled classiness, and arrangements whose complexity augments the tunes rather than overwhelms them.

Neil Tennant is listed as Executive Producer, but it’s Wainwright himself who actually produced these 12 songs, and who navigated his own path from studio to studio, picking up an ever-more bejewelled coterie of musicians along the way. If the vocal tone might often be one of somnambulence, the practicalities of making Release The Stars suggest a very clear head. The castlist includes regulars like sister Martha, mother Kate McGarrigle and Teddy Thompson, venerable actress Sîan Phillips, Tennant on synths, sundry orchestras plus, on lead guitar, Teddy’s father Richard Thompson.

Fortunately, Wainwright is adept at finding grace and space where others would be swamped. The opening “Do I Disappoint You” sees him present a withering defence of his own human frailties, while one orchestral battalion after another mount their attacks and Martha Wainwright (a much stronger singer than her brother, by the by) summons “CHAOS!” and “DESTRUCTION!” like a marauding Fury. The title track, meanwhile, has a brassy Broadway swagger – the result, presumably, of Wainwright immersing himself in that world for his Judy Garland tribute concerts (the song’s lyrical inspiration comes from Lorca Cohen, Leonard’s daughter, missing the New York show). Wainwright, though, is not a belter, and it’s his unsuitability to the top hat and high-kicking routine that makes this grand, flawed finale so compelling.

“Slideshow” is even better, a masterpiece of wry emotional dithering that begins, pointedly, “Do I love you because you treat me so indifferently?/ Or is it the medication?” Pursued by 14 musicians and the London Session Orchestra, he moves at a languid pace through a sequence of euphoric crescendos until, after four minutes, Richard Thompson cuts through the melodrama with a clean, needling solo and Wainwright is left in a lucid reverie, realising, “Do I love you? Yes I do.”

It’s a rare moment of resolution on an album filled with romantic indecision, with dreams of travel and leave-taking. “Between My Legs” is sprightly and uncharacteristically rocking, describing a dysfunctional relationship that can only be consummated with an escape from the city. There are apocalyptic overtones, too, as Wainwright describes a frenzied mass evacuation, then employs Sîan Phillips to incant his words like a spell over another ravishing climax.

If these set pieces initially grab the attention, Release The Stars has other pleasures that reveal themselves more discreetly. “Leaving For Paris” is an

end-of-the-affair piano ballad which intimates that Wainwright’s finest work may yet be solemn and minimal. There’s a baroque, Brel-like trinket called “Tulsa” that claims Brandon Flowers “tastes of potato chips in the morning”.

And finally, amid all the gilt, theatre, recherché poses and brilliant music, there’s a hint that, without the drugs, the castle of indolence might not always be a rewarding place to hang out. “I’m tired of writing elegies to boredom,” he sings in “Sanssouci”, “I just want to be at Sanssouci tonight.” “Sans souci” translates as carefree and, of course, the promise of happiness – “the boys that made me lose the blues” – turns out to be an illusion. When Wainwright arrives at the club it is deserted, and, terminally world-weary, he can only retreat to his melancholy boudoir. If he keeps making albums as good as this, we should wall him up in there forever.

JOHN MULVEY