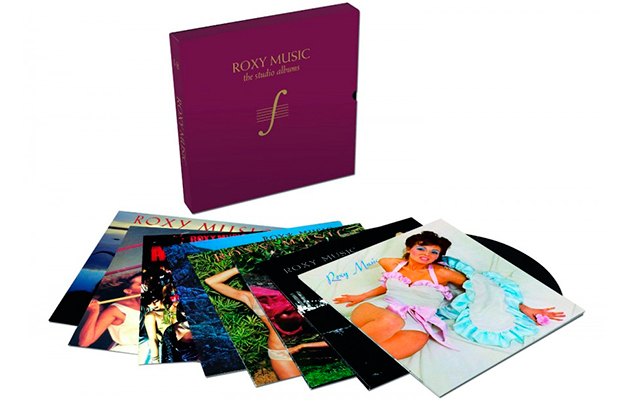

Roxy Music were not best served by the mid-‘80s shift to CDs and especially the subsequent move to mp3 files. At one end of their career, this condensation process made their earlier, more experimental recordings sound tinny and hollow; at the other end, it rendered the lush, expansive sound of the later Roxy thin and pasty, a sort of flock-wallpaper version of their velvet smoothness. So this set of 180gm vinyl albums is to be welcomed, even though it charts more clearly than ever the gradual artistic desiccation that came hand-in-hand with commercial success.

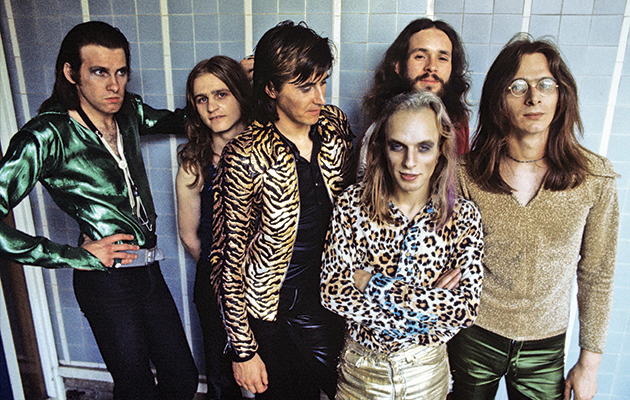

Sadly, the restored analogue warmth can’t really surmount Pete Sinfield’s odd production of Roxy’s debut album, which features the drums upfront and punchy, but leaves the other elements less confidently presented in the mix. But it’s a remarkable record nonetheless, with the track title “Re-make/Re-model” virtually constituting a manifesto of the group’s eclectic, postmodern approach, which featured alongside the modernist strains of tracks such as “Ladytron” hints and tints of doowop, cabaret and even country, and also drew influences from the film, fashion and art worlds. Bits of it might have seemed familiar, but en masse it sounded unlike anything else – as did Bryan Ferry’s mannered crooning, which was a hyper-real representation of the emotional ballast commonly associated with popular music, from Bing Crosby to Marvin Gaye.

Chris Thomas’s production makes the follow-up For Your Pleasure much more assured and propulsive – “Do The Strand’ leaps from the speakers with solidity and purpose, as does “Editions Of You”, with its succinct solos by Andy Mackay, Brian Eno and Phil Manzanera. “For Your Pleasure” and the nine-minute “The Bogus Man” reflect the influence of Can, but it’s the blow-up-doll devotional “In Every Dream Home A Heartache” that really pushes the pop-song envelope, shifting from eerie spatiality to crazed climax, with the false fade and phased return cementing its abstruse weirdness.

Following Eno’s replacement by Curved Air violinist Eddie Jobson, Stranded and Country Life offered a focusing of forces on tracks like “Street Life” and “All I Want Is You”, which extended Roxy’s run of hit singles. Their eclecticism was still in operation – as witness the New Orleans second-line shuffle and gospel choir underscoring Ferry’s testifying on “Psalm” – but the notion “strange ideas mature with age” (from “The Thrill Of It All”) effectively defined Roxy’s developing sound, which despite Manzanera’s terse, edgy guitar striations, was becoming more solid and stable. Ferry’s delivery of hipster slang like “Stay hip/Keep cool”, meanwhile, was still abundantly freighted with irony.

But it was the lumpy funk-rock of “Casanova”, with Ferry’s sardonically punning line about “Now you’re nothing but second hand in glove with second rate” that hinted at what was to come on 1975’s Siren. “Love Is The Drug” irresistibly refined this chic funk style, but the album overall seems sluggish and weak. Even “Both Ends Burning”, the LP’s other standout, lacks impetus, and it’s no surprise that they decided to take a four-year hiatus: the band sounds wiped out, ground down, used up.

By the time they returned, punk had employed its scorched-earth flamethrower, and the fresh buds of new-wave energy were poking through the ruins. Perhaps this explains the uncertainty of Manifesto, an album split between the fizzy, brittle sound of “Trash” and the more expansive, funk-jazz style of the title-track and “Stronger Through The Years”, with its fretless bass and prog-scape noodling. Ferry may have claimed, on “Manifesto”, that he was “for a life around the corner, that takes you by surprise”, but the use of sessioneers like Steve Ferrone, Rick Marotta and Richard Tee indicated the more mainstream territory being mapped out. “Dance Away” was divinely mousse-light, but the album’s other single “Angel Eyes” was stodgy rather than elegant, limp rather than louche.

The following year, Flesh + Blood became the album which crystallised the synthetic glamour and bogus elegance of the nascent New Romantic movement, offering a template for the likes of Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet and ABC. There was a wafer-thin charm about “Oh Yeah” and “Over You”, singles almost entirely lacking in ambition; but the band were struggling for decent material, to the extent of including dilute covers of “In The Midnight Hour” and “Eight Miles High”, the latter re-cast as sylph-like funk – it fits the Roxy aesthetic, but conveys none of the spaced-out alienation of The Byrds’ original.

The band’s swansong came with 1982’s Avalon, the sleekest entry in their catalogue, so vaporous that the title-track could be the soundtrack to a scent advert, while Phil Manzanera’s guitar, for so long the supplier of Roxy’s more exploratory frissons, reached on “Take A Chance With Me” a rarefied, emotive quality akin to Norwegian angstmeister Terje Rypdal. But the true signifier of the band’s fate could be found in its most crucial component, Bryan Ferry’s voice, which had lost all trace of the irony and bite of early Roxy. Trapped with the enervated swoon of a jaded lothario, he had effectively become what he once parodied.