Great artists will often fall into two camps. On the one hand are the precocious types – the likes of Orson Welles, Mozart or Rimbaud – who create their best material in the white-hot intensity of their youth before burning out. On the other hand are the plodders and perfectionists – the Cézannes, the Hitchcocks, the Mark Twains – who work at their craft, getting better with age, always tinkering and experimenting with new ideas.

Weller is one of those rare types who is both a Welles and a Hitchcock, a Rimbaud and a Twain. He released his angry, precocious debut LP – The Jam’s In The City – 40 years ago this month, and had penned half a dozen deathless national anthems before his 21st birthday. Yet here he is in his late fifties, still poking around the fringes of music, still getting enthused by new ideas. In the last few months alone he’s got his old friend Robert Wyatt out of retirement for a short UK tour, collaborated on the new album by UK soul collective Stone Foundation, and completed the experimental soundtrack to a gritty boxing movie called Jawbone, starring Ray Winstone and Ian McShane. He even appeared, rather bizarrely, in the final episode of the BBC’s Sherlock – as a prostrate client in a Viking costume.

A Kind Revolution shows that Weller’s Indian summer of creativity – one that started with 2008’s 22 Dreams – shows no sign of ending as he inches towards his 60th birthday next year. “Can’t seem to let it go!” he howls on one of the standout tracks here, the sci-fi glam rocker “Nova”. “There’s too much to do.” For someone who admits he was struggling with writer’s block only a dozen or so years ago, it’s a nice problem to have.

He’s assisted, as ever, by younger musicians who are always used inventively. One key collaborator is Andy Crofts, who provides guitars, bass guitar, Moog, Hammond, Philicorda organ and backing vocals on much of the album. Weller has long been a fan of his Northamptonshire Acid Jazz outfit The Moons, and some of their psych funk and surf rock voicings have found their way into Weller’s sonic vocabulary here. There’s also Josh McClorey, guitarist and co-lead singer from Irish rock band The Strypes, who Weller describes as one of “the great rock ’n’ roll guitarists of his generation”. But, interestingly, McClorey is steered well clear of meat-and-potatoes heavy rock on his three guest tracks – “Nova”, the gumbo-fried funk of “Woo Sé Mama”, and filtered disco of “One Tear”.

It’s not quite as radical as other recent moments in the Weller canon – there are no nods to AMM or Alice Coltrane and no collaborations with, say, Kevin Shields or the Amorphous Androgynous. Instead, the innovation comes in how Weller and his producer Jan Stan Kybert reassemble their arcane influences and put them through a distinctly Weller-esque prism. “She Moves With The Fayre”, for instance, is an angular piece of funk – with a drumbeat pitched somewhere between New Orleans gumbo and jerky Nigerian Afrobeat – that suddenly lurches into a piece of dreamy symphonic soul in the middle-eight, like the Rotary Connection fronted by Robert Wyatt. “Nova”, another stand-out, seems to deconstruct David Bowie’s entire career and reassemble it in a pleasingly random order. It starts with Eno-esque drones, proceeds with Berlin-era angularities and Scary Monsters-era synth riffs, and then has a baritone sax playing glam-rock stomps, all tied together with a space-age lyric.

“One Tear” sees Weller revisiting house music, with a guest vocal from Boy George, who was always one of the few ’80s pop stars that Weller seemed to have nothing but praise for. In Style Council days he might have got Boy George to sing the entire song, but here he just provides a suitably haunted, tearful introduction. “These tears will flood the earth/The earth will start to turn/A turn that starts it all/More tears will have to fall.”

This dystopian vibe doesn’t last long. “New York” is a soul epic in which Weller recalls the start of his relationship (“that crystal kiss”) with his backing singer Hannah Andrews, who would later become his wife. The same Hannah provides high-pitched gospel-style backing vocals on “The Cranes Are Back”, a kind of slo-mo R&B anthem, which continues the positive feel. “There are no chains on my back,” he hollers. “There’s only the joy that freedom brings.”

Even when he’s not going for formal innovation, this is a master craftsman, someone who knows how to cobble together a verse, chorus, bridge and middle eight as well as any McCartney or Bacharach. “Hopper” is a lovely, shuffling, heart-tugging tribute to the American painter, who “dreams in muted symphonies”. Closing track “The Impossible Idea” is an acoustic jazz-waltz that recalls one of Weller’s wonderfully bucolic old B-sides – like “English Rose”, “Spin Drifting” or “Down In The Seine” – but this time there’s a wistfulness that comes with age, one that chimes with the central idea of “a kind revolution”. The “impossible idea” is that one held by the angry young Weller, that one person can change the world. “All you can do is change yourself,” he concludes.

Q&A

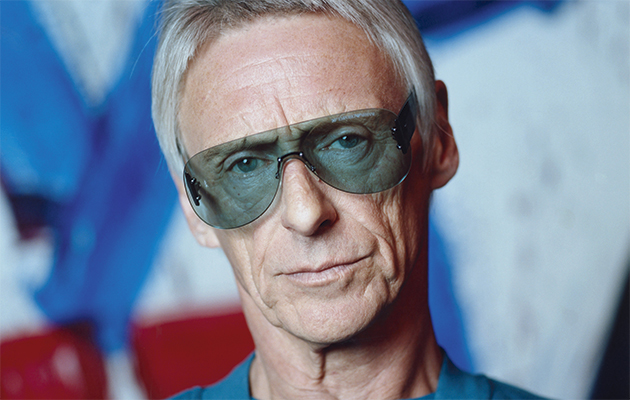

Paul Weller

How did the Boy George collaboration happen?

I’ve always wanted to do a song with him, since the ’80s, man. I love that maturity and soulfulness in his voice, and it perfectly suited “One Tear”. We were meant to be doing something on Saturns Pattern together, but it didn’t happen. I hope we’re going to do some writing together, too.

And Robert Wyatt is there, of course…

Yeah, we got the complicated middle-eight of “She Moves With The Fayre” and I knew it would work with his voice. I love his trumpet playing, too – it reminds me of Donald Byrd on that solo. It was terrific to do those Corbyn dates with him, too, last year. First time he’s played live in God knows how long. I’d love him to guest on a few one-off dates. He sounds great with a band behind him.

How has your songwriting routine changed over the years?

Sometimes I still write in a traditional way. Something like “The Impossible Idea” or “Hopper” I just wrote on an acoustic guitar, like I’ve always done. But, on a track like “One Tear”, it started with my producer Jan Stan Kybert coming in with a loose backing track idea. We’ll work on that, rearrange it, and I’ll add different vocal ideas, bit by bit, as we go along. So some songs are written much more experimentally.

Did you start working on this album as soon as you finished Saturns Pattern two years ago?

Yeah. My missus, Hannah, she was saying, “Aren’t you going to take a bit of a break now?” The thing is, it’s not really down to me. If the songs are coming, I have to follow them. They might dry up next year! I’ve even written most of the next album, which I want to get out in September 2018. Working title: ‘True Meanings’. At the moment the arrangements are acoustic, with some string arrangements. But I want to do some co-writes, too.

INTERVIEW JOHN LEWIS