The grunge-blues giant returns, now digging deeper grooves and - shock! - nu disco... To say that Mark Lanegan’s reputation precedes him is a monumental understatement. Over a 25-year career, he’s carved himself a profile as resolutely rock as any on Mount Rushmore – one that includes spells of homelessness and imprisonment and frequent rehab. He’s also been extraordinarily prolific and a tirelessly enthusiastic collaborator, fronting volatile psychedelic grunge exponents Screaming Trees, joining Josh Homme in Queens Of The Stone Age and Greg Dulli in both The Twilight Singers and The Gutter Twins, fronting grunge-blues soundscapers Soulsavers and across three albums playing Lee Hazlewood to Isobel Campbell’s Nancy Sinatra. None of which has done much to shift the perception of Lanegan as a troubled and notoriously taciturn, heavily tattooed titan of brooding alternative rock. His seventh album as the captain of his own ship may not overturn that reputation, but it is Lanegan’s most accessible to date and boasts two tracks that are such a departure from his familiar, self-described “death dirges” that they might well see him cross over from cultish acclaim to commercial success. All things are relative, however and Blues Funeral – the title almost comic in its playing to expectation – features the man’s trademark blend of slow-burning menace, lowering, blues-stained melancholy and gnarly alt.rock. It’s hardly a cheerful listen and Lanegan’s voice – a ravaged, bottom-of-the-well growl– is as compelling as it ever was, but the experimentation of 2004’s Bubblegum has now bedded in, flourishing alongside a textured heaviosity and easy-swinging grooves that source classic rock and country, electronic punk and krautrock, as well as Lanegan’s own history. QOTSA mates Homme and guitarist Alain Johannes (also at the recording desk) are again on board, along with Dulli and former Pearl Jam drummer, Jack Irons. “Gravedigger’s Song” opens, its throbbing, Neu!-like pulse establishing the album’s motorik framework much as the title does its gloomy lyrical concerns, which inform both the sulphurous “Bleeding Muddy Water” and “St Louis Elegy”, a terrific, Morricone/Orbison hybrid full of cavernous echo, where an electronic whine whips around Lanegan’s voice like the cruellest Arctic wind. The pace picks up with “Gray Goes Black”, its insistent swing as much that of hips on a club floor as a hangman’s rope and for “There’s a Riot in My House”, whose needling riffs bear Homme’s unmistakeable hallmark. Elsewhere, there are nods to Johnny Cash (“Phantasmagoria Blues”), Alice Coltrane (“Leviathan”) and Fairport Convention (“Deep Black Vanishing Train”). Lanegan’s is a seductive, highly personal and distinctive take on blues rock, his expression one of few that renders archetypes – the addict, the doubter, the drifter, the damned soul – as flesh and blood, rather than clichés. All of which makes the album’s wild cards appear doubly odd. Both strikingly atypical of a Mark Lanegan record, if not radical in their actual sound, “Quiver Syndrome” and “Ode to Sad Disco” show just how much he’s changed since the bare-boned, confessional alt.country/folk of his 1990 debut, The Winding Sheet. The former is an unapologetically heads-down, party-starting nod to “Sympathy for the Devil” that suggests Screaming Trees jamming with Primal Scream and was born to be blasted out of a car stereo on the open road, while “Ode to Sad Disco” sounds – impossibly, brilliantly – as if Lanegan has been bending an ear to Goldfrapp. Intended as an homage to “Sad Disco”, a piece of instrumental music by Keli Hlodversson from the second film in Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn’s Pusher trilogy, it marks the album’s halfway point. The nouveau disco/hi-NRG-house thump is tempered by notes of Killing Joke and lyrics that seem to underline the dark side of chemical euphoria, but its sweet, pumped-up hit potential still comes as a shock. Lanegan recently joked that should the cultish acclaim he’s enjoyed for years ever translate to commercial success, he’d move to a beach in Tahiti and stay there for the rest of his life. On the evidence of “Quiver Syndrome” and “Ode to Sad Disco” alone, he might want to start packing his floral shirts. Sharon O'Connell Q&A Mark Lanegan How did it feel to take the wheel again, after years of collaboration? It felt so good. I enjoyed all the other stuff I’ve done in between the last album and this one, but I look at these records as an opportunity to do whatever I’m into at the time, whereas with the other stuff I’m either helping support someone else’s vision or I’m in a partnership with somebody else. What were you into at the time? During the writing and recording I was listening to a lot of krautrock; it’s not new for me, but it was a particularly heavy phase. Bands like Kraftwerk, Kluster, Neu! and Harmonia – I used some of that electronic stuff on (i)Bubblegum(i) but in a noisier and harsher way. This time around, I wanted to use it in a way that was a little more…beautiful. Why did you choose to write some of the new songs on electronic gear? I ended up buying a couple of drum machines and Casios and a synthesizer and was messing around on them, so the album came out of that – although half the songs were written on guitar. That forced me to write a different kind of song, and also ended up influencing the way they sounded. I was trying to make something representative of a record I’d personally like to listen to, I guess. INTERVIEW: SHARON O’CONNELL

The grunge-blues giant returns, now digging deeper grooves and – shock! – nu disco…

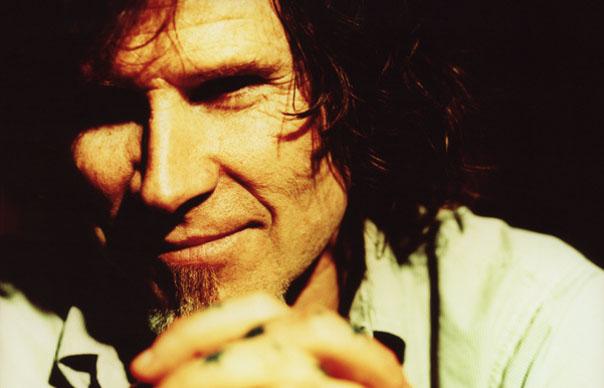

To say that Mark Lanegan’s reputation precedes him is a monumental understatement. Over a 25-year career, he’s carved himself a profile as resolutely rock as any on Mount Rushmore – one that includes spells of homelessness and imprisonment and frequent rehab. He’s also been extraordinarily prolific and a tirelessly enthusiastic collaborator, fronting volatile psychedelic grunge exponents Screaming Trees, joining Josh Homme in Queens Of The Stone Age and Greg Dulli in both The Twilight Singers and The Gutter Twins, fronting grunge-blues soundscapers Soulsavers and across three albums playing Lee Hazlewood to Isobel Campbell’s Nancy Sinatra. None of which has done much to shift the perception of Lanegan as a troubled and notoriously taciturn, heavily tattooed titan of brooding alternative rock.

His seventh album as the captain of his own ship may not overturn that reputation, but it is Lanegan’s most accessible to date and boasts two tracks that are such a departure from his familiar, self-described “death dirges” that they might well see him cross over from cultish acclaim to commercial success. All things are relative, however and Blues Funeral – the title almost comic in its playing to expectation – features the man’s trademark blend of slow-burning menace, lowering, blues-stained melancholy and gnarly alt.rock. It’s hardly a cheerful listen and Lanegan’s voice – a ravaged, bottom-of-the-well growl– is as compelling as it ever was, but the experimentation of 2004’s Bubblegum has now bedded in, flourishing alongside a textured heaviosity and easy-swinging grooves that source classic rock and country, electronic punk and krautrock, as well as Lanegan’s own history. QOTSA mates Homme and guitarist Alain Johannes (also at the recording desk) are again on board, along with Dulli and former Pearl Jam drummer, Jack Irons.

“Gravedigger’s Song” opens, its throbbing, Neu!-like pulse establishing the album’s motorik framework much as the title does its gloomy lyrical concerns, which inform both the sulphurous “Bleeding Muddy Water” and “St Louis Elegy”, a terrific, Morricone/Orbison hybrid full of cavernous echo, where an electronic whine whips around Lanegan’s voice like the cruellest Arctic wind. The pace picks up with “Gray Goes Black”, its insistent swing as much that of hips on a club floor as a hangman’s rope and for “There’s a Riot in My House”, whose needling riffs bear Homme’s unmistakeable hallmark. Elsewhere, there are nods to Johnny Cash (“Phantasmagoria Blues”), Alice Coltrane (“Leviathan”) and Fairport Convention (“Deep Black Vanishing Train”).

Lanegan’s is a seductive, highly personal and distinctive take on blues rock, his expression one of few that renders archetypes – the addict, the doubter, the drifter, the damned soul – as flesh and blood, rather than clichés. All of which makes the album’s wild cards appear doubly odd. Both strikingly atypical of a Mark Lanegan record, if not radical in their actual sound, “Quiver Syndrome” and “Ode to Sad Disco” show just how much he’s changed since the bare-boned, confessional alt.country/folk of his 1990 debut, The Winding Sheet. The former is an unapologetically heads-down, party-starting nod to “Sympathy for the Devil” that suggests Screaming Trees jamming with Primal Scream and was born to be blasted out of a car stereo on the open road, while “Ode to Sad Disco” sounds – impossibly, brilliantly – as if Lanegan has been bending an ear to Goldfrapp. Intended as an homage to “Sad Disco”, a piece of instrumental music by Keli Hlodversson from the second film in Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn’s Pusher trilogy, it marks the album’s halfway point. The nouveau disco/hi-NRG-house thump is tempered by notes of Killing Joke and lyrics that seem to underline the dark side of chemical euphoria, but its sweet, pumped-up hit potential still comes as a shock.

Lanegan recently joked that should the cultish acclaim he’s enjoyed for years ever translate to commercial success, he’d move to a beach in Tahiti and stay there for the rest of his life. On the evidence of “Quiver Syndrome” and “Ode to Sad Disco” alone, he might want to start packing his floral shirts.

Sharon O’Connell

Q&A

Mark Lanegan

How did it feel to take the wheel again, after years of collaboration?

It felt so good. I enjoyed all the other stuff I’ve done in between the last album and this one, but I look at these records as an opportunity to do whatever I’m into at the time, whereas with the other stuff I’m either helping support someone else’s vision or I’m in a partnership with somebody else.

What were you into at the time?

During the writing and recording I was listening to a lot of krautrock; it’s not new for me, but it was a particularly heavy phase. Bands like Kraftwerk, Kluster, Neu! and Harmonia – I used some of that electronic stuff on (i)Bubblegum(i) but in a noisier and harsher way. This time around, I wanted to use it in a way that was a little more…beautiful.

Why did you choose to write some of the new songs on electronic gear?

I ended up buying a couple of drum machines and Casios and a synthesizer and was messing around on them, so the album came out of that – although half the songs were written on guitar. That forced me to write a different kind of song, and also ended up influencing the way they sounded. I was trying to make something representative of a record I’d personally like to listen to, I guess.

INTERVIEW: SHARON O’CONNELL