Few, if any, TV programmes have worked so meticulously to conjure such a precise intersection of content and form. Mad Men, set in a fictional NYC ad agency at the dawn of the ’60s, looks uncannily like an animation of a magazine advertising spread of the period: every outfit sharp, every hair slicked, every grin radiantly insincere, every human interaction a masque ball of ulterior motives conducted through a swirling silver mist of cigarette smoke. Created by Matthew Weiner, who worked as a writer and producer on later series of The Sopranos, Mad Men is clearly intended to fulfil the modern definition of quality drama. Like The Sopranos, The West Wing or The Wire, Mad Men is made on the assumption that it’s as likely to be watched in splurges on DVD as it is in weekly instalments on TV (in the UK, the BBC seemed to acknowledge as much by interring the series on BBC4 late on Sunday nights). As such, Mad Men represents part of an interesting cultural reversal – just as music, especially among younger consumers, is becoming unmoored from its collectible artefact, the album, so the previously transient, disposable medium of TV is being made more and more in the hope or expectation that people will want to own it. The question, then, is whether Mad Men warrants this sort of devotion. It seems, on the strength of its first season, unfortunately unlikely. Though Mad Men looks fabulous – in a laudable act of period verisimilitude, it’s shot on film – and though the writing, plotting, acting and characterisation are taut, there is an abysmal emptiness at the soul of the series. That’s due principally to the fact that the characters are corrupt, neurotic, self-absorbed, vicious and venal to an extent that makes it desperately difficult to care what happens to them. This does, of course, beg the obvious retort that Mad Men is set in an ad agency, after all, but it doesn’t encourage the passing viewer to invest 13 episodes’ worth of time in it. Which is frustrating, as there’s a great idea struggling beneath the viscous gloss on the surface. Mad Men is a rare reflection of the under-examined America that the ’60s counterculture revolted against, and which was never entirely vanquished: conservative, sexist, racist, boorish, smug, materialist, complacent (the sub-plot of the Sterling Cooper agency working on Richard Nixon’s doomed 1960 presidential run is a beautifully waspish touch). Central figure Donald Draper (Jon Hamm) – the Madison Avenue superstar whose implacable coolness conceals a secret life of infidelities and falsehoods – is one of the most unpleasant creatures ever floated as an anti-hero, rendered relatively bearable only by the utter ghastliness of his colleagues, especially predatory lech Roger Sterling (John Slattery) and unctuous would-be usurper Pete Campbell (an excellent, infuriating Vincent Kartheiser). Even the put-upon female characters fail to elicit sympathy, inhabiting perhaps too comfortably their largely decorative roles in the office. Intentionally or not, what Mad Men most often ends up provoking, as this snakepit of charmless, grasping, unhappy schemers festers and bickers, is idle reflection on which of today’s workaday mores and practices will be regarded as shockingly backward 40 years hence. An ad agency is an apposite setting for an exploration of the distance and the difference between appearance and reality. But, as is often the case with advertising itself, the disconnect between the two can leave the consumer feeling somewhat depressed and aggrieved. Mad Men has been applauded far and wide as a genuinely great TV show, but it’s difficult not to suspect that this is largely for no better reason than that it looks so much like a genuinely great TV show. But with a formidable rank of skeletons still closeted, pending emergence during the second season, due for broadcast later in 2008, this unremittingly bleak, weirdly seductive tragedy has time yet to prove itself. EXTRAS: Commentaries, featurettes. ANDREW MUELLER

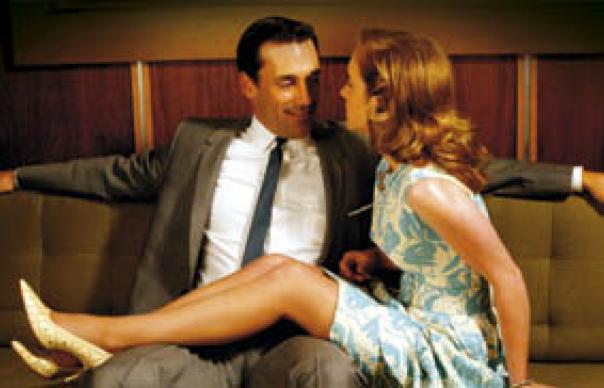

Few, if any, TV programmes have worked so meticulously to conjure such a precise intersection of content and form. Mad Men, set in a fictional NYC ad agency at the dawn of the ’60s, looks uncannily like an animation of a magazine advertising spread of the period: every outfit sharp, every hair slicked, every grin radiantly insincere, every human interaction a masque ball of ulterior motives conducted through a swirling silver mist of cigarette smoke.

Created by Matthew Weiner, who worked as a writer and producer on later series of The Sopranos, Mad Men is clearly intended to fulfil the modern definition of quality drama. Like The Sopranos, The West Wing or The Wire, Mad Men is made on the assumption that it’s as likely to be watched in splurges on DVD as it is in weekly instalments on TV (in the UK, the BBC seemed to acknowledge as much by interring the series on BBC4 late on Sunday nights).

As such, Mad Men represents part of an interesting cultural reversal – just as music, especially among younger consumers, is becoming unmoored from its collectible artefact, the album, so the previously transient, disposable medium of TV is being made more and more in the hope or expectation that people will want to own it.

The question, then, is whether Mad Men warrants this sort of devotion. It seems, on the strength of its first season, unfortunately unlikely. Though Mad Men looks fabulous – in a laudable act of period verisimilitude, it’s shot on film – and though the writing, plotting, acting and characterisation are taut, there is an abysmal emptiness at the soul of the series.

That’s due principally to the fact that the characters are corrupt, neurotic, self-absorbed, vicious and venal to an extent that makes it desperately difficult to care what happens to them. This does, of course, beg the obvious retort that Mad Men is set in an ad agency, after all, but it doesn’t encourage the passing viewer to invest 13 episodes’ worth of time in it.

Which is frustrating, as there’s a great idea struggling beneath the viscous gloss on the surface. Mad Men is a rare reflection of the under-examined America that the ’60s counterculture revolted against, and which was never entirely vanquished: conservative, sexist, racist, boorish, smug, materialist, complacent (the sub-plot of the Sterling Cooper agency working on Richard Nixon’s doomed 1960 presidential run is a beautifully waspish touch).

Central figure Donald Draper (Jon Hamm) – the Madison Avenue superstar whose implacable coolness conceals a secret life of infidelities and falsehoods – is one of the most unpleasant creatures ever floated as an anti-hero, rendered relatively bearable only by the utter ghastliness of his colleagues, especially predatory lech Roger Sterling (John Slattery) and unctuous would-be usurper Pete Campbell (an excellent, infuriating Vincent Kartheiser). Even the put-upon female characters fail to elicit sympathy, inhabiting perhaps too comfortably their largely decorative roles in the office.

Intentionally or not, what Mad Men most often ends up provoking, as this snakepit of charmless, grasping, unhappy schemers festers and bickers, is idle reflection on which of today’s workaday mores and practices will be regarded as shockingly backward 40 years hence.

An ad agency is an apposite setting for an exploration of the distance and the difference between appearance and reality. But, as is often the case with advertising itself, the disconnect between the two can leave the consumer feeling somewhat depressed and aggrieved. Mad Men has been applauded far and wide as a genuinely great TV show, but it’s difficult not to suspect that this is largely for no better reason than that it looks so much like a genuinely great TV show. But with a formidable rank of skeletons still closeted, pending emergence during the second season, due for broadcast later in 2008, this unremittingly bleak, weirdly seductive tragedy has time yet to prove itself.

EXTRAS: Commentaries, featurettes.

ANDREW MUELLER