As he turns 80, Cohen quietly rages against the world with his darkest record for decades... Leonard Cohen, barefoot but dapper in a gun metal gray suit, one morning in June, 1974, sat back in a chair by a window overlooking a busy London street, put his sockless feet on one of the two narrow beds that occupied most of the available space in his modest hotel room, lit a cigarette, a thoughtful scholar addressing an impression that pained him of his songs as miserable, suicidal, in every imaginable way depressing. It seemed to him that he was merely making music fit for a world in which people die and calamity is wholesale, a tough gig. “One often feels inadequate in the face of massacre, disaster and humiliation” he said, courteous, flattering, charming, serious, all of these things. “What, you think, am I doing, singing a song at a time like this? But the worse it gets,” he said, “the more often I find myself picking up a guitar and playing that song. It is, I think, a matter of tradition. You have a tradition on the one hand that says when things are bad, we should play a happy song, a merry tune. Strike up the band and dance the best we can, even if we are suffering from concussion. “And then there’s another tradition, a more Oriental or Middle Eastern tradition, which says that if things are really bad, the best thing to do is sit by the grave and wail, sit next to the disaster and lament. The notion of lamentation seemed to me the way to do it. You don’t avoid the situation. You throw yourself into it, fearlessly.” Cohen at the time had released three albums. A fourth, New Skin For The Old Ceremony, was due out in a couple of months. Over the following 40 years, there would, up to 2012’s Old Ideas, be only eight more studio albums, a modest return for such an extravagant song-writing talent compared to, say, the 21 albums recorded during the same period by Bob Dylan or the jaw-dropping 34 by Neil Young, even taking into account the five years Cohen spent in monastic retreat. While everything he has done has been touched to various extents by the notion as he explained it of lamentation, the poetic articulation of otherwise incoherent grief, there arguably hasn’t been much in his back catalogue since 1971’s Songs Of Love And Hate on which such tragic keening has been so vividly allowed as on the remarkable Popular Problems, released this month, within days of his 80th birthday, a dark new masterpiece, that on songs like “Samson In New Orleans” and “Nevermind” offer front row seats in a theatre of doom. Cohen’s last album, Old Ideas, was an elegant meditation on age, mortality, faith, as beautifully tailored as one of his suits and full of droll poignancies. It was understandably much preoccupied by waning desire, the erotic afterlife of a diminished libido, dwindling virility, noble in the face of the coming inevitable. Its air of stately resignation is largely absent on Popular Problems, however, as if its author has decided that to quietly quit this vale of tears would be somehow dishonourable when his fingers are nimble enough to strum one last song and there is breath enough in his body to sing it. Popular Problems – among which we can probably count conflagration, genocide, the murder of innocents, that kind of thing - is therefore less inward-looking, as if the mirror in front of which Old Ideas was written has been removed from a wall to reveal a window behind it, through which Cohen has lately spent much time in agonised regard of a landscape of conflict, wholesale slaughter, war on every horizon, the world the grave beside which Cohen sits and wails. “Only darkness now,” he announces, his barnacled baritone never so rough, towards the end of “Born In Chains”, which he performed on his last world tour, from which some fans may also remember the bluesy vamp, “My Oh My”, with its tough guitar licks and drawling horns (there’s no place, though, from the tour’s other new songs, for “I’ve Got A Little Secret” and “Feels So Good”, also known as “The Other Blues Song”). On reflection, Old Ideas was perhaps excessively well-groomed, its pedigree sound exquisitely wrought, but somewhat becalmed. And while on Popular Problems Cohen is reunited with former Madonna producer Patrick Leonard and members of the team who contributed to Old Ideas, including backing vocalists The Webb Sisters and Sharon Robinson, whose harmonies continue to provide a feathery counterpoint to Cohen’ sometimes sinister croon, there is more raw drama here, a prevailing starkness. The warm, autumnal glow of Old Ideas is replaced by something more wintry, cracked and menacing. Tracks are sometimes reduced to not much more than Cohen’s cadenced growl, an arterial synthesiser pulse, bluesy Hammond squalls, Bela Santelli’s mournful fiddle, occasional stabbing horn riffs, Cohen himself stirred to something approaching urgency by the sight of a burning world, the camcorder atrocities, the marauding armies, to which he responds with grim vigour and much great writing. That an album inspired by dire universal circumstance opens with a song about fucking may seem odd, even inappropriate. The simmering, pulsating “Slow”, however, celebrates sex as erotic defiance as much as carnal pleasure, Cohen perhaps reminded of a key 60s imperative: make love not war, even as the bombs are falling, all that. The abyss then opens. You probably will have already heard “Almost Like The Blues”, a catalogue of rape and murder that eerily recalls John Cale’s terrifying “Letter From Abroad” (from Hobo Sapiens), minus the Marble Index-style eruptions. “Samson In New Orleans”, like the later “Born In Chains”, has the swell and anguish of a Pentecostal hymn or an old blues spiritual, a beseeching and forlorn lament for the bereft and abandoned – “we who cried for mercy from the bottom of the pit/was our prayer so damned unworthy the sun rejected it?”- that’s perhaps a belated comment on New Orleans’ much-documented post-Katrina agonies, the city’s betrayal by central government whose downfall the song’s narrator here contrives. “A Street” is a song about betrayal and civil war delivered as a hardboiled narrative and played out as domestic farce - “You left me with the dishes and a baby in the bath, you’re tight with the militias, you wear their camouflage” – that thumps along in part like Dylan’s “Early Roman Kings” from Tempest before a haunting climax assumes a more ominous heft. “I see the ghost of culture with numbers on his wrist,” Cohen intones, gravelly, “salute some new solution that all of us have missed...” The album’s greatest curiosity follows. “Did I Ever Love You” opens as a lover’s dark plea before breaking disconcertingly into a frisky country and western hoe-down that may put you in mind of the odd friskiness of “The Captain” from 1984’s Various Positions, by some distance the jauntiest song about The Holocaust yet written. We are returned to more clearly unnerving territory via album highlight “Nevermind”, a fugitive evil on the loose in the land, a tyrant, deposed by war, on the run, a bleak inversion of the heroic French Resistance anthem “The Partisan” covered by Cohen on 1969’s Songs From A Room, whose staccato synthesiser also recalls Talking Heads’ “Life During Wartime”. The album bows out with “You Got Me Singing”, whose title makes it sound like something written for the razzle-dazzle corks-a-popping finale from the golden age of the Hollywood musical, a soundstage full of leggy hoofers kicking up a storm, when in fact its sonorous finger-picked guitar, a signature sound of his early albums, faintly recalls the balm of “Tonight Will Be Fine”, also from Songs From A Room. “You got me singing even though the news is bad,” Cohen sings. “You got me singing the only song I ever had/You got me singing even though the world is gone, you got me thinking, I’d like to carry on,” he continues, surrounded by swirling violin and diaphanous harmonies, his spirit unbroken by time or anything else and fearless to the end. Allan Jones

As he turns 80, Cohen quietly rages against the world with his darkest record for decades…

Leonard Cohen, barefoot but dapper in a gun metal gray suit, one morning in June, 1974, sat back in a chair by a window overlooking a busy London street, put his sockless feet on one of the two narrow beds that occupied most of the available space in his modest hotel room, lit a cigarette, a thoughtful scholar addressing an impression that pained him of his songs as miserable, suicidal, in every imaginable way depressing. It seemed to him that he was merely making music fit for a world in which people die and calamity is wholesale, a tough gig.

“One often feels inadequate in the face of massacre, disaster and humiliation” he said, courteous, flattering, charming, serious, all of these things. “What, you think, am I doing, singing a song at a time like this? But the worse it gets,” he said, “the more often I find myself picking up a guitar and playing that song. It is, I think, a matter of tradition. You have a tradition on the one hand that says when things are bad, we should play a happy song, a merry tune. Strike up the band and dance the best we can, even if we are suffering from concussion.

“And then there’s another tradition, a more Oriental or Middle Eastern tradition, which says that if things are really bad, the best thing to do is sit by the grave and wail, sit next to the disaster and lament. The notion of lamentation seemed to me the way to do it. You don’t avoid the situation. You throw yourself into it, fearlessly.”

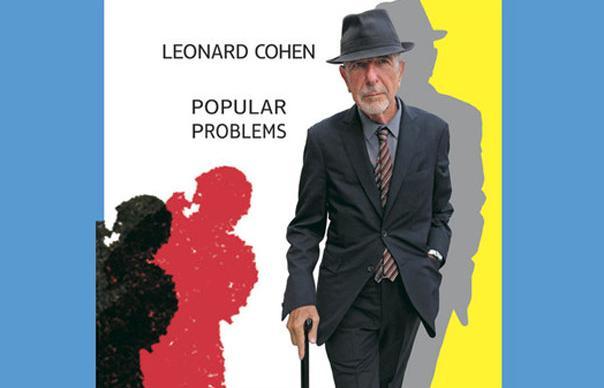

Cohen at the time had released three albums. A fourth, New Skin For The Old Ceremony, was due out in a couple of months. Over the following 40 years, there would, up to 2012’s Old Ideas, be only eight more studio albums, a modest return for such an extravagant song-writing talent compared to, say, the 21 albums recorded during the same period by Bob Dylan or the jaw-dropping 34 by Neil Young, even taking into account the five years Cohen spent in monastic retreat. While everything he has done has been touched to various extents by the notion as he explained it of lamentation, the poetic articulation of otherwise incoherent grief, there arguably hasn’t been much in his back catalogue since 1971’s Songs Of Love And Hate on which such tragic keening has been so vividly allowed as on the remarkable Popular Problems, released this month, within days of his 80th birthday, a dark new masterpiece, that on songs like “Samson In New Orleans” and “Nevermind” offer front row seats in a theatre of doom.

Cohen’s last album, Old Ideas, was an elegant meditation on age, mortality, faith, as beautifully tailored as one of his suits and full of droll poignancies. It was understandably much preoccupied by waning desire, the erotic afterlife of a diminished libido, dwindling virility, noble in the face of the coming inevitable. Its air of stately resignation is largely absent on Popular Problems, however, as if its author has decided that to quietly quit this vale of tears would be somehow dishonourable when his fingers are nimble enough to strum one last song and there is breath enough in his body to sing it. Popular Problems – among which we can probably count conflagration, genocide, the murder of innocents, that kind of thing – is therefore less inward-looking, as if the mirror in front of which Old Ideas was written has been removed from a wall to reveal a window behind it, through which Cohen has lately spent much time in agonised regard of a landscape of conflict, wholesale slaughter, war on every horizon, the world the grave beside which Cohen sits and wails. “Only darkness now,” he announces, his barnacled baritone never so rough, towards the end of “Born In Chains”, which he performed on his last world tour, from which some fans may also remember the bluesy vamp, “My Oh My”, with its tough guitar licks and drawling horns (there’s no place, though, from the tour’s other new songs, for “I’ve Got A Little Secret” and “Feels So Good”, also known as “The Other Blues Song”).

On reflection, Old Ideas was perhaps excessively well-groomed, its pedigree sound exquisitely wrought, but somewhat becalmed. And while on Popular Problems Cohen is reunited with former Madonna producer Patrick Leonard and members of the team who contributed to Old Ideas, including backing vocalists The Webb Sisters and Sharon Robinson, whose harmonies continue to provide a feathery counterpoint to Cohen’ sometimes sinister croon, there is more raw drama here, a prevailing starkness. The warm, autumnal glow of Old Ideas is replaced by something more wintry, cracked and menacing. Tracks are sometimes reduced to not much more than Cohen’s cadenced growl, an arterial synthesiser pulse, bluesy Hammond squalls, Bela Santelli’s mournful fiddle, occasional stabbing horn riffs, Cohen himself stirred to something approaching urgency by the sight of a burning world, the camcorder atrocities, the marauding armies, to which he responds with grim vigour and much great writing.

That an album inspired by dire universal circumstance opens with a song about fucking may seem odd, even inappropriate. The simmering, pulsating “Slow”, however, celebrates sex as erotic defiance as much as carnal pleasure, Cohen perhaps reminded of a key 60s imperative: make love not war, even as the bombs are falling, all that. The abyss then opens. You probably will have already heard “Almost Like The Blues”, a catalogue of rape and murder that eerily recalls John Cale’s terrifying “Letter From Abroad” (from Hobo Sapiens), minus the Marble Index-style eruptions. “Samson In New Orleans”, like the later “Born In Chains”, has the swell and anguish of a Pentecostal hymn or an old blues spiritual, a beseeching and forlorn lament for the bereft and abandoned – “we who cried for mercy from the bottom of the pit/was our prayer so damned unworthy the sun rejected it?”- that’s perhaps a belated comment on New Orleans’ much-documented post-Katrina agonies, the city’s betrayal by central government whose downfall the song’s narrator here contrives.

“A Street” is a song about betrayal and civil war delivered as a hardboiled narrative and played out as domestic farce – “You left me with the dishes and a baby in the bath, you’re tight with the militias, you wear their camouflage” – that thumps along in part like Dylan’s “Early Roman Kings” from Tempest before a haunting climax assumes a more ominous heft. “I see the ghost of culture with numbers on his wrist,” Cohen intones, gravelly, “salute some new solution that all of us have missed…” The album’s greatest curiosity follows. “Did I Ever Love You” opens as a lover’s dark plea before breaking disconcertingly into a frisky country and western hoe-down that may put you in mind of the odd friskiness of “The Captain” from 1984’s Various Positions, by some distance the jauntiest song about The Holocaust yet written. We are returned to more clearly unnerving territory via album highlight “Nevermind”, a fugitive evil on the loose in the land, a tyrant, deposed by war, on the run, a bleak inversion of the heroic French Resistance anthem “The Partisan” covered by Cohen on 1969’s Songs From A Room, whose staccato synthesiser also recalls Talking Heads’ “Life During Wartime”.

The album bows out with “You Got Me Singing”, whose title makes it sound like something written for the razzle-dazzle corks-a-popping finale from the golden age of the Hollywood musical, a soundstage full of leggy hoofers kicking up a storm, when in fact its sonorous finger-picked guitar, a signature sound of his early albums, faintly recalls the balm of “Tonight Will Be Fine”, also from Songs From A Room. “You got me singing even though the news is bad,” Cohen sings. “You got me singing the only song I ever had/You got me singing even though the world is gone, you got me thinking, I’d like to carry on,” he continues, surrounded by swirling violin and diaphanous harmonies, his spirit unbroken by time or anything else and fearless to the end.

Allan Jones