The two sides of Scott-Heron - his early work collected in all its trailblazing glory... When Gil Scott-Heron walked into a small New York studio in Summer 1970, he was an author, not a performer. The gangly 21-year-old had already published a novel and a book of poetry, and had to be persuaded to record a spoken-word album by his new record label Bob Thiele, the man who had overseen the making of Gil’s favourite record, A Love Supreme by John Coltrane. But, as he looked at the few people perched on folding chairs, invited into the studio to make the recording feel live, the prodigy launched into a poem that would change his life. The poem took the form of a list of things that Heron hated; banal icons of white culture and loathed political figures that dominated American television in the 1970’s. By the time Heron had finished reciting “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”, he had unwittingly changed his life. He would no longer be seen as a writer, but a singer, voice of musical black radicalism, doomed junkie… and the man who invented rap. This three-disc reissue of everything Heron and his pianist partner Brian Jackson recorded on Thiele’s Flying Dutchman label would probably not exist if Heron hadn’t bid farewell to that world in May 2011. But for listeners who only know Heron through his final 2010 album I’m New Here, The Revolution Begins… will be a revelation. Not just because it features some great music and poetry, much of which still sounds acutely relevant. But because the man who slowly killed himself with drugs, spent two lengthy periods in prison, and never quite came to terms with his chaotic childhood, prodigious intellect and hatred of white power, is as present and defined and agonized here, in his early twenties, as he is on I’m New Here. Listen to “The Vulture”, or “Who’ll Pay Reparations On My Soul?”, or “Home Is Where The Hatred Is” and you can only come to the chilling conclusion that Gil Scott-Heron knew exactly where he was headed. Ace’s Dean Rudland has applied some neat ingenuity to the box set’s running order. Heron’s Flying Dutchman catalogue comprised three albums: the largely spoken-word debut Small Talk At 125th And Lenox, featuring Last Poets-influenced percussion backing; the full band debut Pieces Of A Man, a key text in the development of jazz-funk featuring Jackson’s subtle keyboards, the familiar, funked-up version of “The Revolution…”, and an extraordinary pick-up band including drummer Bernard ‘Pretty’ Purdie, bassist Ron Carter and flautist Hubert Laws; and the less admired Free Will, which featured one vinyl side of “Pieces…”-style song and one of “Small Talk…”-style poetry. Rudland resists the temptation to just run the albums together, and instead puts the songs onto disc one and the stark beat poetry on disc two. This works perfectly because the moods of Heron’s two early styles are so diametrically opposed. While disc one’s flute and keyboard-led smugglings of modal jazz motifs into pop and soul melodies are Sunday morning mellow, Heron’s radical politics and bracing anger are left undiluted on disc two, which, as it travels from the persuasive satire of “The Revolution…” and “Whitey On The Moon” to the disturbing misogyny and homophobia of “Enough”, “Wiggy” and “The Subject Was Faggots”, forms the core of Heron’s life, work and internalised rage. Like many black radicals of the era, the young Heron was no liberal, and the chasm between his more and less enlightened selves suggests a fractured psyche that proved difficult to live with. Disc three is given up to an ‘alternate’ version of the Free Will album comprised of outtakes, including a radically different, more chaotic version of the title track, while the big attraction for Heron completists is “Artificialness”, a failed but interesting attempt to satirise Vietnam by way of domestic violence recorded with Purdie’s band Pretty Purdie And The Playboys. But while disc one contains a handful of conscious jazz-funk anthems that formed a ready template for acid jazz and its right-on offshoots, its disc two that pins you to your seat with its savage wit and occasionally brutal nastiness. Gil Scott-Heron was always withering about rap when asked if he had, indeed, invented it. But the linguistic mastery, rhythmic reportage and liberal-baiting fury of his early slam poems remain guilty as charged. Just another cross the man had to bear. Garry Mulholland Q&A BRIAN JACKSON Do you still listen to the early records you and Gil made on Flying Dutchman? I do. I feel those records are some of our best work, if not our best performances. We were finding ourselves. Do you recall your first encounter with Gil? Sure! It was at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania in 1969. We ran into each other by accident through a mutual friend, Victor Brown. Victor was performing in a talent show and Gil sang the song that he had written for Victor – it was called “Where Can A Man Find Peace?” – and that pretty much did it for me. His lyrics were unbelievable. We heard what each other were doing and knew we’d be more effective together. Was Lincoln a hotbed of radicalism? Ha! No. I think that’s what fuelled us. The apathy and lack of consciousness we encountered there galvanized us. Did you feel, at the time, that music could effect political change? I was just naïve enough to think that it actually could. But we weren’t interested in inciting people to riot. Some of that early material may sound incendiary, but compared to what people were actually experiencing and feeling inside, it wasn’t. Were you still in touch with Gil when he died? Yes, though not as much as I would have liked to have been. To be honest, I was not shocked. What shocked me more was that he was able to live for so long under the condition he was in. I said goodbye to him long before he actually left the Earth. In some ways I was relieved for him. He was in a lot of pain. Are you still playing? I’ve just done a show at the London Jazz Festival as part of Jazz Funk Legends, a band I’ve put together with Lonnie Liston Smith and Mark Adams, who was Roy Ayers’ music director for many years. We’ll be coming back to Europe next Spring. INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND Pic credit © Chuck Stewart

The two sides of Scott-Heron – his early work collected in all its trailblazing glory…

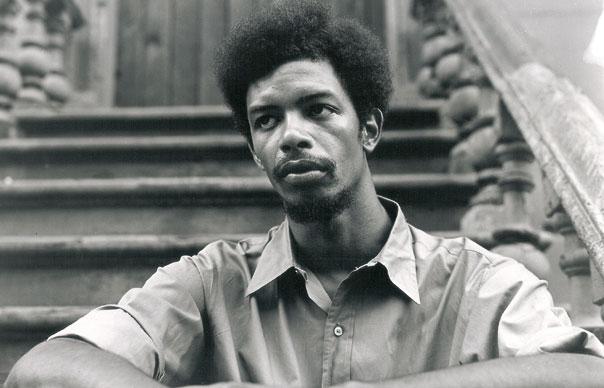

When Gil Scott-Heron walked into a small New York studio in Summer 1970, he was an author, not a performer. The gangly 21-year-old had already published a novel and a book of poetry, and had to be persuaded to record a spoken-word album by his new record label Bob Thiele, the man who had overseen the making of Gil’s favourite record, A Love Supreme by John Coltrane. But, as he looked at the few people perched on folding chairs, invited into the studio to make the recording feel live, the prodigy launched into a poem that would change his life. The poem took the form of a list of things that Heron hated; banal icons of white culture and loathed political figures that dominated American television in the 1970’s.

By the time Heron had finished reciting “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”, he had unwittingly changed his life. He would no longer be seen as a writer, but a singer, voice of musical black radicalism, doomed junkie… and the man who invented rap. This three-disc reissue of everything Heron and his pianist partner Brian Jackson recorded on Thiele’s Flying Dutchman label would probably not exist if Heron hadn’t bid farewell to that world in May 2011. But for listeners who only know Heron through his final 2010 album I’m New Here, The Revolution Begins… will be a revelation. Not just because it features some great music and poetry, much of which still sounds acutely relevant. But because the man who slowly killed himself with drugs, spent two lengthy periods in prison, and never quite came to terms with his chaotic childhood, prodigious intellect and hatred of white power, is as present and defined and agonized here, in his early twenties, as he is on I’m New Here. Listen to “The Vulture”, or “Who’ll Pay Reparations On My Soul?”, or “Home Is Where The Hatred Is” and you can only come to the chilling conclusion that Gil Scott-Heron knew exactly where he was headed.

Ace’s Dean Rudland has applied some neat ingenuity to the box set’s running order. Heron’s Flying Dutchman catalogue comprised three albums: the largely spoken-word debut Small Talk At 125th And Lenox, featuring Last Poets-influenced percussion backing; the full band debut Pieces Of A Man, a key text in the development of jazz-funk featuring Jackson’s subtle keyboards, the familiar, funked-up version of “The Revolution…”, and an extraordinary pick-up band including drummer Bernard ‘Pretty’ Purdie, bassist Ron Carter and flautist Hubert Laws; and the less admired Free Will, which featured one vinyl side of “Pieces…”-style song and one of “Small Talk…”-style poetry. Rudland resists the temptation to just run the albums together, and instead puts the songs onto disc one and the stark beat poetry on disc two.

This works perfectly because the moods of Heron’s two early styles are so diametrically opposed. While disc one’s flute and keyboard-led smugglings of modal jazz motifs into pop and soul melodies are Sunday morning mellow, Heron’s radical politics and bracing anger are left undiluted on disc two, which, as it travels from the persuasive satire of “The Revolution…” and “Whitey On The Moon” to the disturbing misogyny and homophobia of “Enough”, “Wiggy” and “The Subject Was Faggots”, forms the core of Heron’s life, work and internalised rage. Like many black radicals of the era, the young Heron was no liberal, and the chasm between his more and less enlightened selves suggests a fractured psyche that proved difficult to live with.

Disc three is given up to an ‘alternate’ version of the Free Will album comprised of outtakes, including a radically different, more chaotic version of the title track, while the big attraction for Heron completists is “Artificialness”, a failed but interesting attempt to satirise Vietnam by way of domestic violence recorded with Purdie’s band Pretty Purdie And The Playboys. But while disc one contains a handful of conscious jazz-funk anthems that formed a ready template for acid jazz and its right-on offshoots, its disc two that pins you to your seat with its savage wit and occasionally brutal nastiness.

Gil Scott-Heron was always withering about rap when asked if he had, indeed, invented it. But the linguistic mastery, rhythmic reportage and liberal-baiting fury of his early slam poems remain guilty as charged. Just another cross the man had to bear.

Garry Mulholland

Q&A

BRIAN JACKSON

Do you still listen to the early records you and Gil made on Flying Dutchman?

I do. I feel those records are some of our best work, if not our best performances. We were finding ourselves.

Do you recall your first encounter with Gil?

Sure! It was at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania in 1969. We ran into each other by accident through a mutual friend, Victor Brown. Victor was performing in a talent show and Gil sang the song that he had written for Victor – it was called “Where Can A Man Find Peace?” – and that pretty much did it for me. His lyrics were unbelievable. We heard what each other were doing and knew we’d be more effective together. Was Lincoln a hotbed of radicalism? Ha! No. I think that’s what fuelled us. The apathy and lack of consciousness we encountered there galvanized us.

Did you feel, at the time, that music could effect political change?

I was just naïve enough to think that it actually could. But we weren’t interested in inciting people to riot. Some of that early material may sound incendiary, but compared to what people were actually experiencing and feeling inside, it wasn’t.

Were you still in touch with Gil when he died?

Yes, though not as much as I would have liked to have been. To be honest, I was not shocked. What shocked me more was that he was able to live for so long under the condition he was in. I said goodbye to him long before he actually left the Earth. In some ways I was relieved for him. He was in a lot of pain.

Are you still playing?

I’ve just done a show at the London Jazz Festival as part of Jazz Funk Legends, a band I’ve put together with Lonnie Liston Smith and Mark Adams, who was Roy Ayers’ music director for many years. We’ll be coming back to Europe next Spring.

INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND

Pic credit © Chuck Stewart