Early '70s touchstone, expanded to 10 discs... Whether his emerging Las Vegas persona signaled the beginning of the end or the end of his new beginnings was hard to tell. But Elvis Presley, finally putting his cornball movie career behind him, had been consolidating his strengths since his momentous 1968 television comeback. Cutting the finest album of his career (From Elvis in Memphis), diving enthusiastically back into live performance, expanding his repertoire to touch on everything — pop, country, R&B, folk, blues, gospel, and his rock ‘n’ roll roots — Presley was engaged and relevant again, in ways that, astonishingly, sometimes transcended even his watershed beginnings. That’s the Way It Is, the 1970 documentary film and attendant soundtrack, is perched on that precipice, before the miserable ups and downs took hold, when a playful, open, and expansive Elvis was testing his newfound mettle among the pop elite. He’d already done two Vegas residencies in the glow of his comeback, so by the time the cameras rolled that summer he was primed to overtake Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin on their own turf. More than that, though, Presley was positioning himself as the potent, interpretive repository of American music. With his seamless TCB Band (guitarists James Burton and John Wilkinson, bassist Jerry Scheff, pianist Glen Hardin, and drummer Ronnie Tutt), Presley worked up dozens of songs, reaching into his storied past for the hits, but also redefining contemporary pop with illustrious, inimitable cover versions of composers and compositions both famous and obscure. This box — deluxe edition extremis — features DVDs of the original film and a posthumous 2001 edit, and eight CDs covering the original 12-track album, attendant singles, outtakes, a loose, riotous, all-over-the-map set of rehearsals, and the piece de resistance, six complete Vegas concerts. The original album, like much of Elvis’ later output, is a Frankensteined, barely-in-context mix of live tracks and studio cuts (though not without its charms, cf. the desperate “I’ve Lost You”). Presley’s ambitious reach becomes clearer in the box’s wide-angled context, though. From dreamtime ballads (“Mary In The Morning”), twangy country/rockers (“Patch It Up”), and hard blues (“Stranger In My Own Hometown”), to a sweep into the very ether of America’s legacy in song — folk tunes to swamp pop, New Orleans R&B to cowboy songs — Elvis touched on everything. The film, meanwhile, centering on live rehearsal and performance, is a fascinating timepiece, a clash of old-world/new-world cultures and aesthetics that aspires — awkwardly so in places — to convey the magic of Elvis in the post-hippie age. By showtime, he’d mapped out the sets, even as song choices remained surprisingly fluid. Pugnacious rockers “That’s All Right” and “Blue Suede Shoes” framed the sets. Familiar late-’60s radio melodies — the Bee Gees’ “Words,” Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline”—were slotted in, suitably Elvis-ized. Mid-tempo romantic-heartbreak ballads, best for melancholy crooning and sweeping earworm choruses, comprised the heart of the beast: “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” a 1966 hit for Dusty Springfield, and Guy Fletcher’s “Just Pretend” had a dark undertow; others, like “I Just Can’t Help Believin’” and “The Next Step Is Love,” were hopeful, upbeat, overly sentimental. By the time he leans into the Righteous Brothers’ immortal “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” the Sweet Inspirations providing slinky call-and-response, Presley’s feral interpretive skills, his ability to make any song his own, kicks in with a raw, otherwordly force. Touching yet grandiose, schmaltzy yet raucous, Presley operates in broad strokes. Ray Charles’ R&B (“I Got a Woman”), south to Tony Joe White’s swampy rouser “Polk Salad Annie,” respectful nods to the Beatles (“Get Back,” “Something”) to over-the-top weepers (“There Goes My Everything”), even social protest (“In the Ghetto,” “Walk A Mile In My Shoes),” surely weird for Vegas — it all melts into consummate Elvisness. The shows could be inconsistent. He sometimes sabotages performances with goofball jokes — the insecure human beneath the Elvis mask. The old ballads like “Love Me Tender”, which he was tethered to but now held mostly in contempt, suffered most. Goopy sentimentalism ran rampant, too, though balanced by pure power and beauty—best encapsulated in the showstoppers. On “Suspicious Minds,” a six-minute, adrenaline-soaked rollercoaster driven by stirring vocals and Tutt’s windmill drum-fills, Elvis is at his crazed, apoplectic peak. “Bridge Over Troubled Water” the recent Simon and Garfunkel hit, is the soul-bearing obverse, Elvis pouring himself into the song’s gospel hue, its simple message of hope, humanity, and redemption regularly unleashing deeply resonant emotions, a postcard of mercy from the artist and the times. Luke Torn Q&A Ernst Mikael Jorgensen, producer of That’s The Way It Is [Deluxe Edition] With all the live ‘70s Elvis material now available, what sets this one apart? In my view, this is most likely the ultimate highpoint of his artistic career. Aloha from Hawaii may be his greatest commercial achievement. He had just completed a weeks’ worth of sessions in Nashville – enough for three albums – and now a film was going to be made of his show, from rehearsals through to the concerts. He never worked harder – more than 60 songs were rehearsed, 40 of which ended up at the shows. His repertoire was updated with the best of contemporary writing and a handful of smash hits of his own. And he looked great. Summer 1970 seems like an Elvis turning point. How did the shows affect the public’s perception of him? I think the main issue here is that Elvis consolidated his position as a contemporary act as opposed to just a phenomenon from the past. It became the model for his shows for the rest of his life. “Bridge over Troubled Water” and “You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin’” are incredible throughout - any speculation on why he delivered those songs so convincingly? The process of incorporating contemporary songs, made famous by other people, started back in February 1970 with the On Stage album and the hit single “The Wonder of You.” I think Elvis realized that the music world had changed, and the best songwriters now sang their own songs, whether they had good singing voices or not. People like Bob Dylan had definitely shown that audiences were willing to accept lesser voices, as long as the songs were great. And for Elvis, it was always the songs, and the emotions, that counted the most. INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN

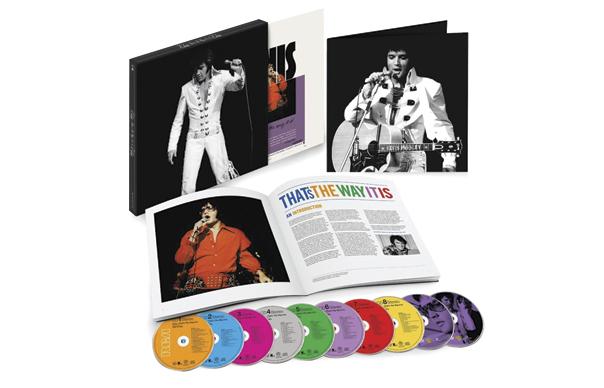

Early ’70s touchstone, expanded to 10 discs…

Whether his emerging Las Vegas persona signaled the beginning of the end or the end of his new beginnings was hard to tell. But Elvis Presley, finally putting his cornball movie career behind him, had been consolidating his strengths since his momentous 1968 television comeback. Cutting the finest album of his career (From Elvis in Memphis), diving enthusiastically back into live performance, expanding his repertoire to touch on everything — pop, country, R&B, folk, blues, gospel, and his rock ‘n’ roll roots — Presley was engaged and relevant again, in ways that, astonishingly, sometimes transcended even his watershed beginnings.

That’s the Way It Is, the 1970 documentary film and attendant soundtrack, is perched on that precipice, before the miserable ups and downs took hold, when a playful, open, and expansive Elvis was testing his newfound mettle among the pop elite. He’d already done two Vegas residencies in the glow of his comeback, so by the time the cameras rolled that summer he was primed to overtake Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin on their own turf.

More than that, though, Presley was positioning himself as the potent, interpretive repository of American music. With his seamless TCB Band (guitarists James Burton and John Wilkinson, bassist Jerry Scheff, pianist Glen Hardin, and drummer Ronnie Tutt), Presley worked up dozens of songs, reaching into his storied past for the hits, but also redefining contemporary pop with illustrious, inimitable cover versions of composers and compositions both famous and obscure.

This box — deluxe edition extremis — features DVDs of the original film and a posthumous 2001 edit, and eight CDs covering the original 12-track album, attendant singles, outtakes, a loose, riotous, all-over-the-map set of rehearsals, and the piece de resistance, six complete Vegas concerts.

The original album, like much of Elvis’ later output, is a Frankensteined, barely-in-context mix of live tracks and studio cuts (though not without its charms, cf. the desperate “I’ve Lost You”). Presley’s ambitious reach becomes clearer in the box’s wide-angled context, though. From dreamtime ballads (“Mary In The Morning”), twangy country/rockers (“Patch It Up”), and hard blues (“Stranger In My Own Hometown”), to a sweep into the very ether of America’s legacy in song — folk tunes to swamp pop, New Orleans R&B to cowboy songs — Elvis touched on everything. The film, meanwhile, centering on live rehearsal and performance, is a fascinating timepiece, a clash of old-world/new-world cultures and aesthetics that aspires — awkwardly so in places — to convey the magic of Elvis in the post-hippie age.

By showtime, he’d mapped out the sets, even as song choices remained surprisingly fluid. Pugnacious rockers “That’s All Right” and “Blue Suede Shoes” framed the sets. Familiar late-’60s radio melodies — the Bee Gees’ “Words,” Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline”—were slotted in, suitably Elvis-ized. Mid-tempo romantic-heartbreak ballads, best for melancholy crooning and sweeping earworm choruses, comprised the heart of the beast: “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” a 1966 hit for Dusty Springfield, and Guy Fletcher’s “Just Pretend” had a dark undertow; others, like “I Just Can’t Help Believin’” and “The Next Step Is Love,” were hopeful, upbeat, overly sentimental. By the time he leans into the Righteous Brothers’ immortal “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” the Sweet Inspirations providing slinky call-and-response, Presley’s feral interpretive skills, his ability to make any song his own, kicks in with a raw, otherwordly force.

Touching yet grandiose, schmaltzy yet raucous, Presley operates in broad strokes. Ray Charles’ R&B (“I Got a Woman”), south to Tony Joe White’s swampy rouser “Polk Salad Annie,” respectful nods to the Beatles (“Get Back,” “Something”) to over-the-top weepers (“There Goes My Everything”), even social protest (“In the Ghetto,” “Walk A Mile In My Shoes),” surely weird for Vegas — it all melts into consummate Elvisness.

The shows could be inconsistent. He sometimes sabotages performances with goofball jokes — the insecure human beneath the Elvis mask. The old ballads like “Love Me Tender”, which he was tethered to but now held mostly in contempt, suffered most. Goopy sentimentalism ran rampant, too, though balanced by pure power and beauty—best encapsulated in the showstoppers.

On “Suspicious Minds,” a six-minute, adrenaline-soaked rollercoaster driven by stirring vocals and Tutt’s windmill drum-fills, Elvis is at his crazed, apoplectic peak. “Bridge Over Troubled Water” the recent Simon and Garfunkel hit, is the soul-bearing obverse, Elvis pouring himself into the song’s gospel hue, its simple message of hope, humanity, and redemption regularly unleashing deeply resonant emotions, a postcard of mercy from the artist and the times.

Luke Torn

Q&A

Ernst Mikael Jorgensen, producer of That’s The Way It Is [Deluxe Edition]

With all the live ‘70s Elvis material now available, what sets this one apart?

In my view, this is most likely the ultimate highpoint of his artistic career. Aloha from Hawaii may be his greatest commercial achievement. He had just completed a weeks’ worth of sessions in Nashville – enough for three albums – and now a film was going to be made of his show, from rehearsals through to the concerts. He never worked harder – more than 60 songs were rehearsed, 40 of which ended up at the shows. His repertoire was updated with the best of contemporary writing and a handful of smash hits of his own. And he looked great.

Summer 1970 seems like an Elvis turning point. How did the shows affect the public’s perception of him?

I think the main issue here is that Elvis consolidated his position as a contemporary act as opposed to just a phenomenon from the past. It became the model for his shows for the rest of his life.

“Bridge over Troubled Water” and “You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin’” are incredible throughout – any speculation on why he delivered those songs so convincingly?

The process of incorporating contemporary songs, made famous by other people, started back in February 1970 with the On Stage album and the hit single “The Wonder of You.” I think Elvis realized that the music world had changed, and the best songwriters now sang their own songs, whether they had good singing voices or not. People like Bob Dylan had definitely shown that audiences were willing to accept lesser voices, as long as the songs were great. And for Elvis, it was always the songs, and the emotions, that counted the most.

INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN