From humble ivory-tickler to global sensation - the singer-songwriter's rise chronicled... For pianist Reginald Dwight of Pinner, the 1970s began with intermittent, uncredited session work. By the end of the decade, he’d changed his name legally to Elton Hercules John, bought a football club, rewritten glam-rock’s dress code to include full-body animal costumes, topped the American charts eleven times and signed the most lucrative recording contract the world had ever seen. As Greg Shaw wrote in 1975, “His songs are on every radio station, every hour of every day... While everyone was looking for the Next Big Thing, Elton quietly strolled in and took the throne.” ‘Quietly’ is the interesting word there. It might seem ill-chosen for a performer whose flamboyance rivalled Liberace’s. But although there’s the odd melodramatic outburst on this five-album boxset – Elton John, Tumbleweed Connection, Madman Across The Water, Honky Château and Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player – what these songs are primarily tailored for is personal space. It’s music of privacy, daydream and travel. Elton was not a self-analyst or a confess-all type like the Laurel Canyon songwriters (for one thing, he didn’t write his own lyrics), so he couldn’t quite touch raw nerves. But watch the “Tiny Dancer” scene in Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous to see what Elton could do. Lost in their thoughts, the people on the bus listen in silence to the US hit from Madman Across The Water. Then one or two start joining in. Soon there’s a collective chorus: the blue-jeaned seamstress is in their emotional bloodstream. Some people find the scene excruciatingly sentimental. Think of it more as historical. It’s how Elton strolled in and took the throne. Elton John (1970), the first album in the boxset, was actually his second. (His debut, Empty Sky, has evidently slipped the compilers’ memory.) Straight away we’re into “Your Song”: rippling piano, discreetly plucked guitar, a surge of violins. Bernie Taupin, Elton’s lyricist, is intentionally tongue-tied (“but then again, no”) in the role of a hung-up secret admirer who’s hopeless at expressing his feelings. The song is both corny and pure, and, like the best McCartney, seems to glide effortlessly from first bar to last. The Elton John album was made by young men. Elton was 22, Taupin 19, guitarist Caleb Quaye 21 and musical arranger Paul Buckmaster 23. The precocity is impressive. Taupin is all about American mythology and old men’s regrets. Elton likes his harps and harpsichords. Together they gaze beyond England. “No Shoe Strings On Louise”, an enthusiastic C&W lollop, grasps for the language of an imagined time (“hoedown”, “boss man”), as if British dramatists had turned their hand to writing an episode of The Little House On The Prairie. Yet their narrative structures seem believable. Aretha Franklin would hardly have covered “Border Song” if she’d sensed any phoniness. Maybe their fandom shone through: on the rock gospel number “Take Me To The Pilot”, Elton and Taupin clearly have their hearts in the South. Elton would even adopt a Southern accent to better suit the locations. He and Suzie hold “hay-unds” in “Crocodile Rock” (Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player), while the shackled black men in “Slave” (Honky Château) have a “river running sweat through our lay-und.” Taupin was so passionate about American history that his vision of the Wild West dominated Tumbleweed Connection (1970). Here were 19th century frontiers painted in words by a movie buff from Lincolnshire. But his imagery is highly convincing – “the swallow and the sycamore” in the valley, the “fat stock” hiding in the east – and Elton, charged with setting Taupin’s sepia photos to music, brings epic dimensions to the album’s standout tracks (“Burn Down The Mission”, “Where To Now St. Peter?”). Melody and metaphor meet irresistibly in the latter’s opening and closing line (“I took myself a blue canoe”) – six words of ineffable freedom. Populated with men named Deacon Lee and Old Clay, not to mention blind gunslingers bent on settling arguments with bullets, Tumbleweed Connection naturally aspired to the antique charm of The Band’s brown album. But when’s all said and done, Tumbleweed Connection is a testament to the power of two imaginations working dynamically in tandem. Taupin remained committed to the idea of America as a land where a song could combine authenticity and fantasy. And of course he would overreach. There’s woodsmoke over the tepees in “Indian Sunset” (Madman Across The Water, 1971), where Yellow Dog’s tribesmen “run the gauntlet of the Sioux”. It doesn’t smack of personal experience somehow. “Holiday Inn”, on the same album, underreaches. Dully remarking on the facelessness of American hotels, Taupin’s boredom seems contagious: Elton’s humdrum chorus could have been composed in his sleep. Millions of songs like this were written in the ’70s, but Elton and Taupin had a unique problem. Unless Elton cast them in glittering melodies, Taupin’s tall tales had the taint of fakery. When they both got it right, they pulled off a heavyweight drama like Madman Across The Water’s title track. In this haunting piece, an inmate of an asylum, who’s just received a family visit, fixates on a broken boat that he can see from his window. The distracted, paranoid lyrics have been subjected to endless interpretation. There was even a popular theory that Taupin was writing about Richard Nixon – presumably having had a 1971 premonition of Watergate (!). Elton now had a full-time band – Davey Johnstone (guitar), Dee Murray (bass) and Nigel Olsson (drums) – who debuted as a recording unit on Honky Château (1972). The No 2 hit “Rocket Man” propelled Elton to the forefront of British pop – after two albums without a UK single – but his comprehensive glam makeover was still a year away. On the cover of Honky Château he’s very much a serious artist: bearded, glowering. He excels as a pianist, driving the buoyantly syncopated music forward like Dr John on Gumbo. There’s the taste of the South again. There’s a tragicomic suicide threat. There are several cats. Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player (1973), featuring the worldwide hits “Daniel” and “Crocodile Rock”, immersed itself in the ’50s. Something of a rock’n’roll pastiche, proceedings get a bit Bryclreemed and mindless in places. The absolute highlight is “Blues For My Baby And Me”, a story about two runaways where you’re never quite sure what fateful outcome Taupin has in mind. Like all the albums in this boxset, Don’t Shoot Me... is the same configuration (and master) as the 1995 Mercury editions (‘The Classic Years’ series), containing the same bonus tracks as before, including the nine-minute original version of “Madman Across The Water” (on Tumbleweed Connection) and the wonderful 1970 B-side “Grey Seal” (on Elton John). “Grey Seal” was later re-recorded for the hit-packed 1973 double album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. And at that point, in a whirl of ermine, the throne was duly ascended. DAVID CAVANAGH

From humble ivory-tickler to global sensation – the singer-songwriter’s rise chronicled…

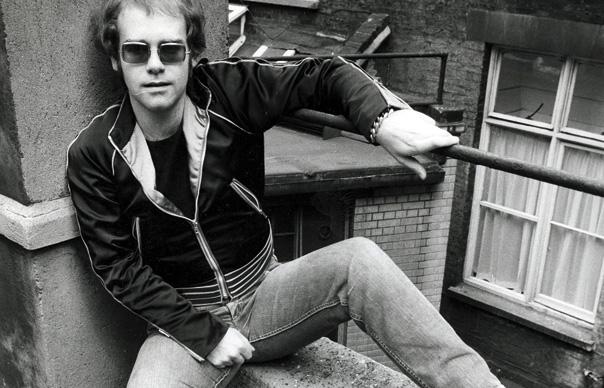

For pianist Reginald Dwight of Pinner, the 1970s began with intermittent, uncredited session work. By the end of the decade, he’d changed his name legally to Elton Hercules John, bought a football club, rewritten glam-rock’s dress code to include full-body animal costumes, topped the American charts eleven times and signed the most lucrative recording contract the world had ever seen. As Greg Shaw wrote in 1975, “His songs are on every radio station, every hour of every day… While everyone was looking for the Next Big Thing, Elton quietly strolled in and took the throne.”

‘Quietly’ is the interesting word there. It might seem ill-chosen for a performer whose flamboyance rivalled Liberace’s. But although there’s the odd melodramatic outburst on this five-album boxset – Elton John, Tumbleweed Connection, Madman Across The Water, Honky Château and Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player – what these songs are primarily tailored for is personal space. It’s music of privacy, daydream and travel. Elton was not a self-analyst or a confess-all type like the Laurel Canyon songwriters (for one thing, he didn’t write his own lyrics), so he couldn’t quite touch raw nerves. But watch the “Tiny Dancer” scene in Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous to see what Elton could do. Lost in their thoughts, the people on the bus listen in silence to the US hit from Madman Across The Water. Then one or two start joining in. Soon there’s a collective chorus: the blue-jeaned seamstress is in their emotional bloodstream. Some people find the scene excruciatingly sentimental. Think of it more as historical. It’s how Elton strolled in and took the throne.

Elton John (1970), the first album in the boxset, was actually his second. (His debut, Empty Sky, has evidently slipped the compilers’ memory.) Straight away we’re into “Your Song”: rippling piano, discreetly plucked guitar, a surge of violins. Bernie Taupin, Elton’s lyricist, is intentionally tongue-tied (“but then again, no”) in the role of a hung-up secret admirer who’s hopeless at expressing his feelings. The song is both corny and pure, and, like the best McCartney, seems to glide effortlessly from first bar to last.

The Elton John album was made by young men. Elton was 22, Taupin 19, guitarist Caleb Quaye 21 and musical arranger Paul Buckmaster 23. The precocity is impressive. Taupin is all about American mythology and old men’s regrets. Elton likes his harps and harpsichords. Together they gaze beyond England. “No Shoe Strings On Louise”, an enthusiastic C&W lollop, grasps for the language of an imagined time (“hoedown”, “boss man”), as if British dramatists had turned their hand to writing an episode of The Little House On The Prairie. Yet their narrative structures seem believable. Aretha Franklin would hardly have covered “Border Song” if she’d sensed any phoniness. Maybe their fandom shone through: on the rock gospel number “Take Me To The Pilot”, Elton and Taupin clearly have their hearts in the South. Elton would even adopt a Southern accent to better suit the locations. He and Suzie hold “hay-unds” in “Crocodile Rock” (Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player), while the shackled black men in “Slave” (Honky Château) have a “river running sweat through our lay-und.”

Taupin was so passionate about American history that his vision of the Wild West dominated Tumbleweed Connection (1970). Here were 19th century frontiers painted in words by a movie buff from Lincolnshire. But his imagery is highly convincing – “the swallow and the sycamore” in the valley, the “fat stock” hiding in the east – and Elton, charged with setting Taupin’s sepia photos to music, brings epic dimensions to the album’s standout tracks (“Burn Down The Mission”, “Where To Now St. Peter?”). Melody and metaphor meet irresistibly in the latter’s opening and closing line (“I took myself a blue canoe”) – six words of ineffable freedom. Populated with men named Deacon Lee and Old Clay, not to mention blind gunslingers bent on settling arguments with bullets, Tumbleweed Connection naturally aspired to the antique charm of The Band’s brown album. But when’s all said and done, Tumbleweed Connection is a testament to the power of two imaginations working dynamically in tandem.

Taupin remained committed to the idea of America as a land where a song could combine authenticity and fantasy. And of course he would overreach. There’s woodsmoke over the tepees in “Indian Sunset” (Madman Across The Water, 1971), where Yellow Dog’s tribesmen “run the gauntlet of the Sioux”. It doesn’t smack of personal experience somehow. “Holiday Inn”, on the same album, underreaches. Dully remarking on the facelessness of American hotels, Taupin’s boredom seems contagious: Elton’s humdrum chorus could have been composed in his sleep. Millions of songs like this were written in the ’70s, but Elton and Taupin had a unique problem. Unless Elton cast them in glittering melodies, Taupin’s tall tales had the taint of fakery. When they both got it right, they pulled off a heavyweight drama like Madman Across The Water’s title track. In this haunting piece, an inmate of an asylum, who’s just received a family visit, fixates on a broken boat that he can see from his window. The distracted, paranoid lyrics have been subjected to endless interpretation. There was even a popular theory that Taupin was writing about Richard Nixon – presumably having had a 1971 premonition of Watergate (!).

Elton now had a full-time band – Davey Johnstone (guitar), Dee Murray (bass) and Nigel Olsson (drums) – who debuted as a recording unit on Honky Château (1972). The No 2 hit “Rocket Man” propelled Elton to the forefront of British pop – after two albums without a UK single – but his comprehensive glam makeover was still a year away. On the cover of Honky Château he’s very much a serious artist: bearded, glowering. He excels as a pianist, driving the buoyantly syncopated music forward like Dr John on Gumbo. There’s the taste of the South again. There’s a tragicomic suicide threat. There are several cats. Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player (1973), featuring the worldwide hits “Daniel” and “Crocodile Rock”, immersed itself in the ’50s. Something of a rock’n’roll pastiche, proceedings get a bit Bryclreemed and mindless in places. The absolute highlight is “Blues For My Baby And Me”, a story about two runaways where you’re never quite sure what fateful outcome Taupin has in mind. Like all the albums in this boxset, Don’t Shoot Me… is the same configuration (and master) as the 1995 Mercury editions (‘The Classic Years’ series), containing the same bonus tracks as before, including the nine-minute original version of “Madman Across The Water” (on Tumbleweed Connection) and the wonderful 1970 B-side “Grey Seal” (on Elton John). “Grey Seal” was later re-recorded for the hit-packed 1973 double album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. And at that point, in a whirl of ermine, the throne was duly ascended.

DAVID CAVANAGH