DIR: QUENTIN TARANTINO | ST: KURT RUSSELL, ROSARIO DAWSON, JORDAN LADD, ROSE McGOWAN SYNOPSIS Austin DJ Jungle Julia flirts dangerously with Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell), a charming psychopath with an interest in “vehicle homicide”. A year later, in Tennessee, another group of girls test drive a Dodge Challenger, and the chase is on... Quentin Tarantino approaches filmmaking the way an astronaut might enter a flight simulator. There is a precise control of atmosphere, and occasional weightlessness, but the nagging sensation remains that he is merely playing. So Reservoir Dogs was his tribute to the heist movie, Jackie Brown his entry into blaxploitation, and the Kill Bills his nods to the choreographed violence of the Far East. Only in Pulp Fiction did Tarantino define a world of his own, and that was a post-modern funpark. Along the way, the director misplaced his audience. That there’s still a market for this kind of thing is shown by the success of the Ocean’s 11 franchise, which is essentially Reservoir Dogs with expensive teeth. But Death Proof, in its original guise as half of Grindhouse – a double-bill with Robert Rodriguez’s Planet Terror – flopped in the US, and the two parts have now been left to fend for themselves. It seems odd to say it, but perhaps the unpopularity of Grindhouse was because it was too successful in its execution. The films Tarantino and Rodriguez were paying tribute to were shoestring affairs, with limited narratives, playing on damaged prints, and relying for their continued existence on hucksterism: promising more (sex, drugs, violence, or whatever deviant behaviour was suddenly fashionable) than they delivered. Fine for a suburban fleapit in the 1970s, but a tough sell for the multiplex, as the director himself admits below. And it’s true, Death Proof is unburdened by traditional concerns such as plot or characterisation. With all due respect to the gnarled charisma of Kurt Russell, it doesn’t come with a marquee name attached. The director is the star. So. There are two sets of chicks. The first, led by Jungle Julia (Sydney Tamiia Poitier), a DJ in Austin, Texas, like to do ordinary girlish things: they wear hotpants, cuss, get high, make out in parking lots, and dance like horny tigresses. They encounter Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell) in a bar and, despite the fact that he drives a muscle car with death decals, collectively fail to notice that he is a dangerous psychopath. Some months later, Mike and his car stalk an even feistier group of girls, including Rosario Dawson and Mary Elizabeth Winstead (pictured right). These ladies, encouraged by stuntwoman Zoë Bell, playing herself (she was Uma’s double in Kill Bill) decide to take a test-drive in a white 1970 Dodge Challenger with a 440 engine, as a tribute to Vanishing Point, with Bell playing “ship’s mast” on the roof. This becomes an even more reckless manoeuvre when Stuntman Mike’s black Dodge takes up pursuit. This is male fantasy made flesh, so the girls are all long legs and beestung lips, and improbably interested in obscure pop and the road movies of the 1970s. Sometimes, the girltalk drags, but Russell is faultless, displaying a brand of self-parody that makes Travolta’s turn in Pulp Fiction look like a gang show audition. Plausible? No. But it is beautifully designed, splicing from faded colour to a stunning black-and-white section with the clunk of a coin in a Big Red soda machine. The music is great. The car chase is a blast. As a study of Americana it is fetishistic, whether Tarantino’s camera is devouring the action of a jukebox stylus on a Stax 45, or scanning the label of a Wild Turkey bottle. Yes, Death Proof is as indulgent as it is nostalgic. As a film about film, and an expensive celebration of cheap thrills, it exists in that uneasy space between tribute and parody, but the overall effect is quietly subversive. It is Tarantino’s first art movie. Trash art, but art nonetheless. ALASTAIR McKAY

DIR: QUENTIN TARANTINO | ST: KURT RUSSELL, ROSARIO DAWSON, JORDAN LADD, ROSE McGOWAN

SYNOPSIS

Austin DJ Jungle Julia flirts dangerously with Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell), a charming psychopath with an interest in “vehicle homicide”. A year later, in Tennessee, another group of girls test drive a Dodge Challenger, and the chase is on…

Quentin Tarantino approaches filmmaking the way an astronaut might enter a flight simulator. There is a precise control of atmosphere, and occasional weightlessness, but the nagging sensation remains that he is merely playing. So Reservoir Dogs was his tribute to the heist movie, Jackie Brown his entry into blaxploitation, and the Kill Bills his nods to the choreographed violence of the Far East. Only in Pulp Fiction did Tarantino define a world of his own, and that was a post-modern funpark.

Along the way, the director misplaced his audience. That there’s still a market for this kind of thing is shown by the success of the Ocean’s 11 franchise, which is essentially Reservoir Dogs with expensive teeth. But Death Proof, in its original guise as half of Grindhouse – a double-bill with Robert Rodriguez’s Planet Terror – flopped in the US, and the two parts have now been left to fend for themselves.

It seems odd to say it, but perhaps the unpopularity of Grindhouse was because it was too successful in its execution. The films Tarantino and Rodriguez were paying tribute to were shoestring affairs, with limited narratives, playing on damaged prints, and relying for their continued existence on hucksterism: promising more (sex, drugs, violence, or whatever deviant behaviour was suddenly fashionable) than they delivered. Fine for a suburban fleapit in the 1970s, but a tough sell for the multiplex, as the director himself admits below.

And it’s true, Death Proof is unburdened by traditional concerns such as plot or characterisation. With all due respect to the gnarled charisma of Kurt Russell, it doesn’t come with a marquee name attached. The director is the star.

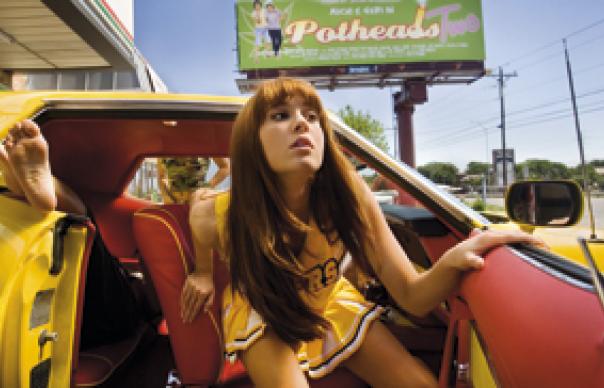

So. There are two sets of chicks. The first, led by Jungle Julia (Sydney Tamiia Poitier), a DJ in Austin, Texas, like to do ordinary girlish things: they wear hotpants, cuss, get high, make out in parking lots, and dance like horny tigresses. They encounter Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell) in a bar and, despite the fact that he drives a muscle car with death decals, collectively fail to notice that he is a dangerous psychopath.

Some months later, Mike and his car stalk an even feistier group of girls, including Rosario Dawson and Mary Elizabeth Winstead (pictured right). These ladies, encouraged by stuntwoman Zoë Bell, playing herself (she was Uma’s double in Kill Bill) decide to take a test-drive in a white 1970 Dodge Challenger with a 440 engine, as a tribute to Vanishing Point, with Bell playing “ship’s mast” on the roof. This becomes an even more reckless manoeuvre when Stuntman Mike’s black Dodge takes up pursuit.

This is male fantasy made flesh, so the girls are all long legs and beestung lips, and improbably interested in obscure pop and the road movies of the 1970s. Sometimes, the girltalk drags, but Russell is faultless, displaying a brand of self-parody that makes Travolta’s turn in Pulp Fiction look like a gang show audition.

Plausible? No. But it is beautifully designed, splicing from faded colour to a stunning black-and-white section with the clunk of a coin in a Big Red soda machine. The music is great. The car chase is a blast. As a study of Americana it is fetishistic, whether Tarantino’s camera is devouring the action of a jukebox stylus on a Stax 45, or scanning the label of a Wild Turkey bottle.

Yes, Death Proof is as indulgent as it is nostalgic. As a film about film, and an expensive celebration of cheap thrills, it exists in that uneasy space between tribute and parody, but the overall effect is quietly subversive. It is Tarantino’s first art movie. Trash art, but art nonetheless.

ALASTAIR McKAY