Charley Varrick (Walter Matthau) makes a living robbing banks. Low risk hits, as a rule, small concerns, mainly, in out of the way places across the Southwest, where there’ll be enough money to pay off the muscle he runs with and turn a decent profit for himself.

Charley’s not greedy for big scores, because he knows they bring headlines and heat, unwanted publicity and more attention from the law than he cares to deal with. He’s a sensible guy who knows his limits.

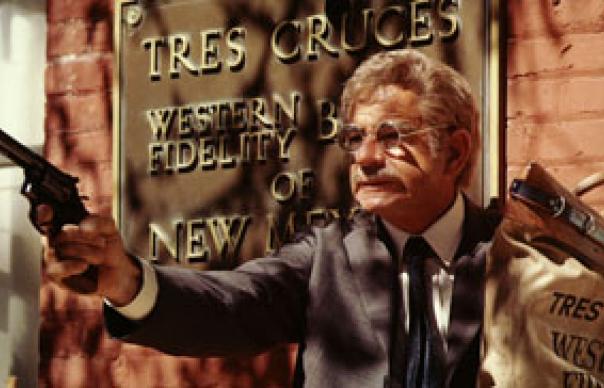

All seems to be going well in Charley’s world until one morning, the small New Mexico town of Tres Cruces coming awake around them, he and his crew hit the local bank and everything goes badly wrong, as things in movies like this so often do.

The botched heist leaves bodies everywhere and Charley wondering as he counts the loot where all the money came from. Which is when he realises he’s accidentally just ripped off the Mafia, who’ve been using the bank to launder the illegal skim from gambling, narcotics, prostitution, whatever. There’s nearly three quarters of a million bucks in the bags he’s stolen, and Charley knows the Mob aren’t going to rest until they’ve got it back. He knows also they are probably already looking for him, and he also knows what they’ll do when they find him – which they will, there being nowhere really to run when the guys are this pissed off. What Charley decides to do next is disappear, and what the film that follows is about is how he tries do it.

Charley Varrick was director Don Siegel’s 1973 follow-up to Dirty Harry, which had given him the biggest hit of a 30 year career and is a highlight of five films he made with Clint Eastwood, to whom he was as much a mentor as Sergio Leone had earlier been (Eastwood’s Unforgiven is dedicated to ‘Sergio and Don’). Siegel’s early reputation was for no-nonsense genre movies like Riot In Cell Block 11and the sci-fi classic The Invasion Of the Body Snatchers, films that through his craft and intelligence wholly transcended their meagre budgets.

Siegel was used to working with some of Hollywood’s toughest actors – Clint, of course, and also Steve McQueen in the savage war film Hell Is For Heroes, Lee Marvin in The Killers, Richard Widmark in the astonishingly bleak New York cop movie, Madigan. He pulled off something of a casting masterstroke here, however, by handing the title role of Charley Varrick to Walter Matthau, whose dolorous hangdog features audiences were most used to seeing in comic roles in films like The Fortune Cookie and The Odd Couple, two of the 10 movies he made with his friend Jack Lemmon.

Matthau had made his debut as a heavy, however, in Burt Lancaster’s 1945 frontier western, The Kentuckian, in which a scene that has him flogging Lancaster with a bull-whip was considered so violent it was heavily censored. He doesn’t have to flay anyone alive here, but credibly brings a tough uncompromising doggedness to the part, and it was a shock to see an actor more famous for playing loveable curmudgeons essaying Charley’s unsentimental pragmatism and ruthless determination to stay alive. And, yes, he’ll kill if he has to as he tries to keep one step ahead of Joe Don Baker’s Molly, a pipe-smoking Mafia enforcer, an intractable killer who in some ways foreshadows Javier Bardem’s Anton Chigurth in No Country For Old Men.

Apart from the opening bank raid, there’s a lack of the explicit violence you might expect from a Siegel film. We see Molly slap a couple of people around, one of them in a wheel chair, and he gives Charley’s feckless sidekick Harman Sullivan (Andy Robinson, who played Dirty Harry’s serial killer, Scorpio) a terrible going over, but his menace is in his manner, which is insidiously, relentlessly cruel. There’s certainly nothing here, however, that compares to, say, the ferocity of Hell Is For Heroes or the malevolence of Lee Marvin and Clu Gulager terrorising a home full of blind people in The Killers and in truth Siegel’s not much bothered with the absence of conventional action, the current need to blow something up every five minutes to keep the crowd’s attention.

He’s more interested in character and the levels of duplicity Charley encounters as he engineers an escape, which brings him in touch with serial odd-balls, all of whom betray him as soon as they’ve got a cut of his money, none of which buys their loyalty, making them instead greedy for more.

The story’s played out over a couple of days, the clock ticking for Charley as Molly closes in, mayhem coming with him. But Siegel doesn’t push things too hard. The pace in fact is laconic to the point of being leisurely, you might even say at times lackadaisical. This disguises to some extent the film’s sardonic undertow, the way it works as a satire on both Hollywood, corporate America and the crookedness of Nixon’s White House, then coming to an end via the Watergate revelations.

Charley’s a former stunt pilot turned crop duster forced into crime by the big business takeover of small operations like his own. His business card describes him as ‘The Last Of The Independents’ – “I like that,” smirks Molly. “It has an air of finality to it” – and it’s to Siegel’s amused relish that Charley, idiosyncratic, resourceful, full of the native cunning of someone who has learned to rely on no one but himself, goes into the final reckoning with Molly with an outside chance of getting out of all this alive.

EXTRAS: 1* Scene selection, stills gallery.

ALLAN JONES