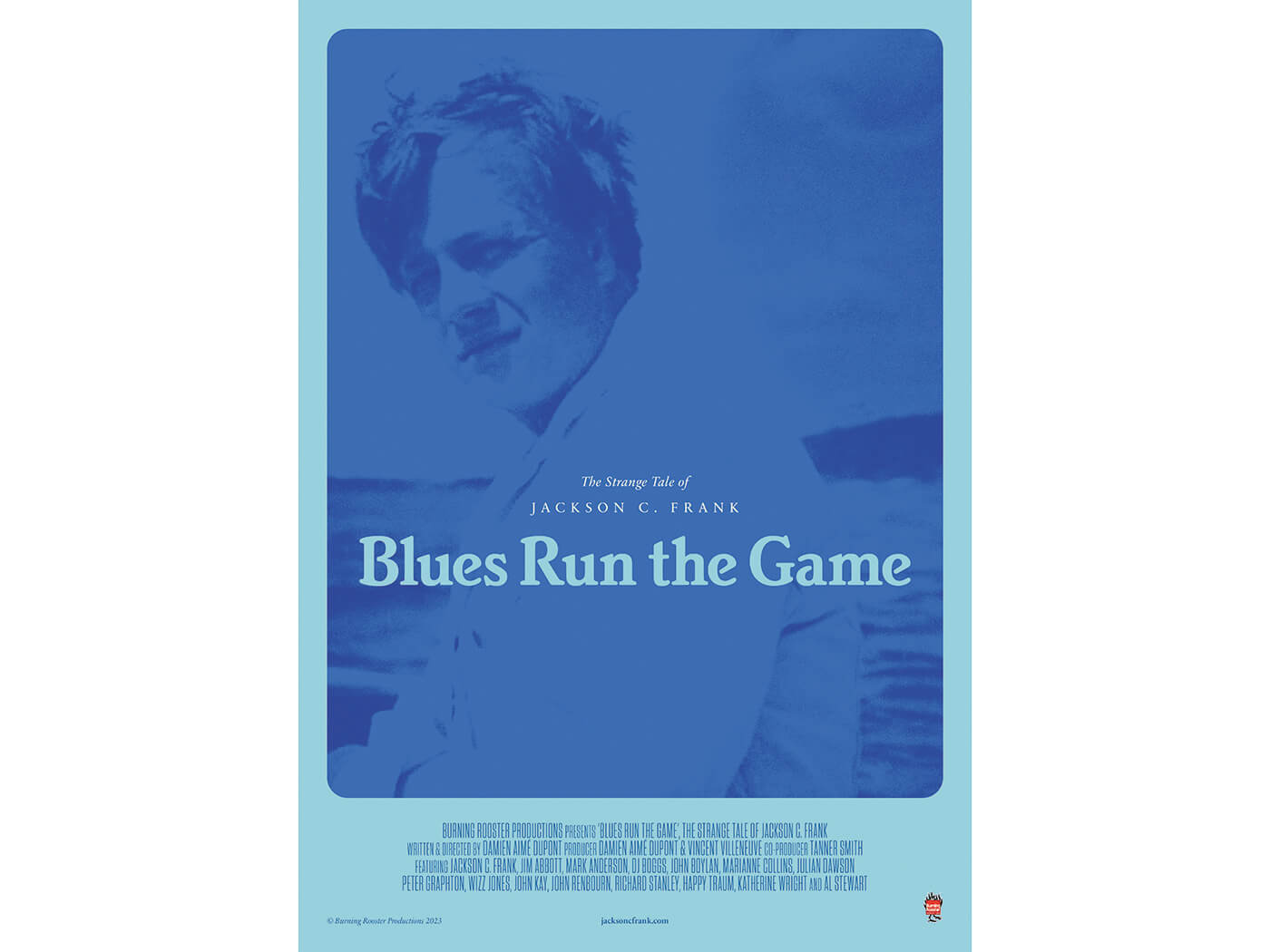

After making one uniquely influential album in 1965, Jackson Carey Frank lived for another third of a century without ever releasing another record. In this compassionate and often deeply moving documentary, the French filmmaker Damien Aime Dupont sets out to explain what made that solitary album so special – and what went so tragically wrong that we never heard from Frank again.

Recorded in London and produced by his American compatriot Paul Simon, Frank’s album was a gem of finger-picking folk guitar full of striking songs, including the enduring “Blues Run The Game”, since covered by everyone from Bert Jansch to Laura Marling.

Yet in the annals of doomed folk troubadours of the 1960s/70s, his fate was arguably the cruellest of them all. Frank’s tragedy was not that he was cut down in his prime but that he endured a protracted physical and mental agony as he lived on as a paranoid schizophrenic into his late fifties in a twilight world of turmoil and pain, a broken, unrecognisable figure shuffling between living on the streets and time in mental institutions.

The thesis of Dupont’s film – supported by interviews with early girlfriend Katherine Wright and others – is that Frank never recovered emotionally from a fire at his school in Buffalo when he was 11. He escaped out of a window with terrible burns but 15 of his classmates died and he suffered survivor’s guilt for the rest of his life.

One of his songs, “Marlene”, was about a girl who perished in the fire. Jim Abbott, a friend who in later years helped him claim his unpaid royalties, can barely keep his emotion in check as he recites its final verse: “The fire it burned her life out, it left me little more/ I am a crippled singer, and it evens up the score”.

Dupont’s problem is the paucity of archive material. The celluloid legacy consists mostly of black and white stills and where there is a tiny fragment of him performing live – probably at Les Cousins in London in 1965 – the audio has been lost and the film is instead superimposed with a spooked soundtrack of avant-garde noise; presumably intended to convey catharsis, it is used liberally throughout the film.

This means Dupont’s relies heavily on talking heads. There are insightful reminiscences from those who knew him at different stages of his life, including John Renbourn, Wizz Jones and Al Stewart, comrades on the London folk scene in the 1960s. Presumably Paul Simon, who was as close to Frank as anyone, declined to be interviewed.

The poverty in which he died in a homeless mission in 1998 was made more poignant by learning that when he turned 21 he received a 100,000 dollars insurance pay-out from the fire. Equivalent to a million today, within a couple of years it had all been squandered. While living in London, he was infamous for turning up to folk club gigs in an Aston Martin or a Bentley.

The film ends with Renbourn performing “Blues Run The Game” but there is simply not enough primary material to make for a great film. Had Dupont chosen instead to make a radio documentary– as Uncut’s Laura Barton did for BBC Radio 4 a dozen years ago – it could have been a contender for a Sony award.