Black America’s militant years, captured on rediscovered Swedish documentaries. Right on! Black America’s brave fight for emancipation during the 1960s and 1970s started with the Civil Rights marches of Dr Martin Luther King and ended in the ignominy of ghettos awash with hard drugs and crime. The struggle was not without victories – the end of legalised segregation in the South, the emergence of an honoured class of black artists and intellectuals (even a black President in the White House) – but the sense of failure is far more profound. It’s a long fall from the optimism of King’s ‘I Have A Dream’ speech and the great albums of Curtis Mayfield and Stevie Wonder to the misogny of Gangster Rap and the underclass squalor depicted in The Wire. Using a cache of forgotten documentaries discovered in a Stockholm basement, Black Power Mixtape is a juddering return to the hopes, conflicts and sinister political plays of the Black American Uprising. The movie is a time capsule, and while its 90 minutes are an inevitably incomplete portrait, its footage – most of it finely shot in black and white and with some terrific interviews – offers a mesmerising glimpse into an under-documented era. Here is a coolly militant Stokely Carmichael – the man who coined the term ‘Black Power’ - in 1967 with his critique of Dr King’s non-violent protests – “It was founded on the false assumption that America has a conscience – it doesn’t.” Here is Angela Davis, the Stones’ “Sweet Black Angel”, welling with tears and anguish under her giant Afro as she faces the death penalty on trumped-up charges. Here is Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver in 1970, defiant but clearly broken by his enforced exile in Algeria. Alongside such charismatic headline-makers come shocking scenes of police brutality on protesters, vox pop interviews, Black Panther soup kitchens, and glimpses of the seedy New York that provided the scenario for The French Connection. There’s even a surreal cameo of a Swedish bus tour of Harlem from 1973, with well-heeled Scands rubbernecking at the Big Apple’s mean streets. The material was shot for Swedish television. Sweden’s criticism of the US ’s uncompromising response to black protest, specifically the ‘show trials’ of dissidents in the early 1970s and the apparently co-ordinated assassination of black power firebrands, led to the Nixon regime breaking off diplomatic relations with the historically neutral country in 1972, an event unimaginable today. Presented chronologically, the original footage is sensibly left unadorned, though there are voice-overs from modern times. Angela Davis (now a retired professor) reflects that “They meant to send me to the death chamber simply because I was a convenient figure.” The story that emerges from the film’s assemblage is of an unyielding and corrupt US government prepared to go to extreme and at times murderous lengths to eliminate its critics. The Vietnam war provides an intrusive backdrop to the story. In 1967 the US had over 500,000 troops in Vietnam (today there are 68,000 in Afghanistan), a disproportionate number of them black Americans (cf Platoon and Apocalypse Now). Martin Luther King’s widening of the civil rights struggle to a “Stop The War” stance is, it’s implied by several commentators, the reason behind his assassination. “He was tampering with the playground of the wealthy,” reckons singer, actor and activist Harry Belafonte. The proliferation of hard drugs in black ghettoes in the early 1970s is another, shadowy strand of the tale. Smacked-out Vietnam veterans were part of the problem (“they weren’t killed on active service, they OD’d,” comes one voice), but it’s suggested that the CIA also fuelled the heroin boom to quell dissent. With its leaders silenced or exiled, its street warriors imprisoned or addicted, its optimism dismayed, Black America’s revolt wilted. The humanitarian, democratic impulses of the King years give way to Marxist cant – the Panthers become “the vanguard of the People’s party” – and the apocalyptic tones of the Nation of Islam. The 1974 allegation by Louis Farrakhan, a former calypso singer, that “the white race is one of devils” is a low point. Neil Spencer

Black America’s militant years, captured on rediscovered Swedish documentaries. Right on!

Black America’s brave fight for emancipation during the 1960s and 1970s started with the Civil Rights marches of Dr Martin Luther King and ended in the ignominy of ghettos awash with hard drugs and crime. The struggle was not without victories – the end of legalised segregation in the South, the emergence of an honoured class of black artists and intellectuals (even a black President in the White House) – but the sense of failure is far more profound. It’s a long fall from the optimism of King’s ‘I Have A Dream’ speech and the great albums of Curtis Mayfield and Stevie Wonder to the misogny of Gangster Rap and the underclass squalor depicted in The Wire.

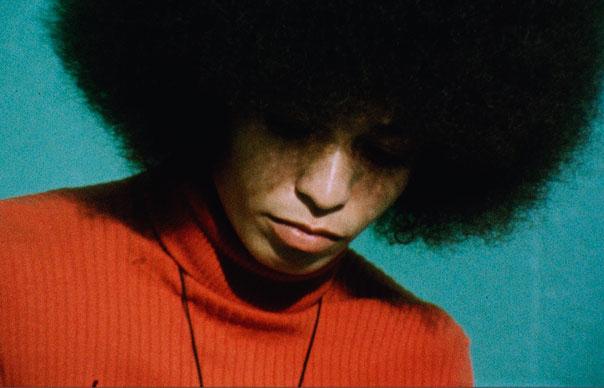

Using a cache of forgotten documentaries discovered in a Stockholm basement, Black Power Mixtape is a juddering return to the hopes, conflicts and sinister political plays of the Black American Uprising. The movie is a time capsule, and while its 90 minutes are an inevitably incomplete portrait, its footage – most of it finely shot in black and white and with some terrific interviews – offers a mesmerising glimpse into an under-documented era. Here is a coolly militant Stokely Carmichael – the man who coined the term ‘Black Power’ – in 1967 with his critique of Dr King’s non-violent protests – “It was founded on the false assumption that America has a conscience – it doesn’t.” Here is Angela Davis, the Stones’ “Sweet Black Angel”, welling with tears and anguish under her giant Afro as she faces the death penalty on trumped-up charges. Here is Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver in 1970, defiant but clearly broken by his enforced exile in Algeria.

Alongside such charismatic headline-makers come shocking scenes of police brutality on protesters, vox pop interviews, Black Panther soup kitchens, and glimpses of the seedy New York that provided the scenario for The French Connection. There’s even a surreal cameo of a Swedish bus tour of Harlem from 1973, with well-heeled Scands rubbernecking at the Big Apple’s mean streets.

The material was shot for Swedish television. Sweden’s criticism of the US ’s uncompromising response to black protest, specifically the ‘show trials’ of dissidents in the early 1970s and the apparently co-ordinated assassination of black power firebrands, led to the Nixon regime breaking off diplomatic relations with the historically neutral country in 1972, an event unimaginable today. Presented chronologically, the original footage is sensibly left unadorned, though there are voice-overs from modern times. Angela Davis (now a retired professor) reflects that “They meant to send me to the death chamber simply because I was a convenient figure.” The story that emerges from the film’s assemblage is of an unyielding and corrupt US government prepared to go to extreme and at times murderous lengths to eliminate its critics.

The Vietnam war provides an intrusive backdrop to the story. In 1967 the US had over 500,000 troops in Vietnam (today there are 68,000 in Afghanistan), a disproportionate number of them black Americans (cf Platoon and Apocalypse Now). Martin Luther King’s widening of the civil rights struggle to a “Stop The War” stance is, it’s implied by several commentators, the reason behind his assassination. “He was tampering with the playground of the wealthy,” reckons singer, actor and activist Harry Belafonte.

The proliferation of hard drugs in black ghettoes in the early 1970s is another, shadowy strand of the tale. Smacked-out Vietnam veterans were part of the problem (“they weren’t killed on active service, they OD’d,” comes one voice), but it’s suggested that the CIA also fuelled the heroin boom to quell dissent.

With its leaders silenced or exiled, its street warriors imprisoned or addicted, its optimism dismayed, Black America’s revolt wilted. The humanitarian, democratic impulses of the King years give way to Marxist cant – the Panthers become “the vanguard of the People’s party” – and the apocalyptic tones of the Nation of Islam. The 1974 allegation by Louis Farrakhan, a former calypso singer, that “the white race is one of devils” is a low point.

Neil Spencer