On December 1, 1969, the Bill Evans Trio began a month-long season at Ronnie Scott’s Club in London. They followed Thelonious Monk, who had been in residence for three weeks with his quartet. That’s how it was in the days when jazz clubs with a capacity of a couple of hundred could host world-famous artists for several weeks at time.

It was a system that allowed groups to take advantage of stable working conditions, developing their music together without the worries involved in packing up and moving on to a new venue every day. The same piano, the same acoustics, even the same hotel and the same food for an extended period: a lot of musicians will tell you that they wish such arrangements were on offer today. After all, jazz might have sounded very different without Evans’ run at the Village Vanguard in 1961, when he, Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian took the opportunity to redesign the internal mechanism of the basic piano trio.

LaFaro was dead and Motian had moved on by the time Evans arrived in the last month of the decade at a Soho club where he always felt comfortable. His position in the jazz firmament was well established, after a rise that began in 1959 when Miles Davis hired him to set the mood for Kind Of Blue. His ability to infuse the techniques of modern jazz piano – specifically the drive of the young Horace Silver and the adventurousness of Lennie Tristano – with the harmonic voicings of Chopin and Debussy could be said to have introduced jazz to impressionism.

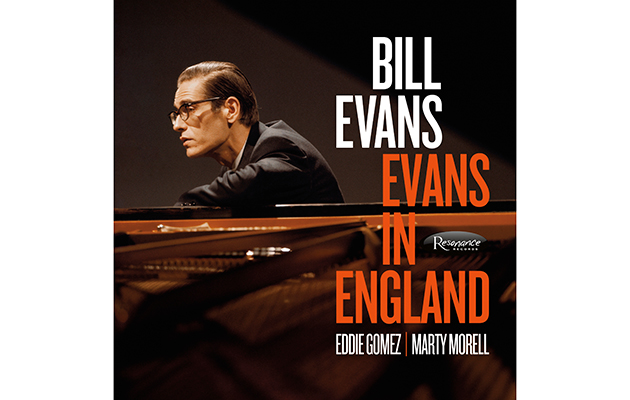

Now he was accompanied by Eddie Gomez on double bass and Marty Morell on drums; neither would become game-changers in the manner of their predecessors, but they were certainly up to the job. Meanwhile their leader was in the throes of a long-term heroin addiction that shocked some of his associates but never got in the way of his music. Like other jazz musicians of his generation, he was allowing his hair to grow, but his style remained essentially conservative in sound and appearance.

By 1969, as these newly discovered tapes show, his approach had solidified: the trio’s repertoire consisted of a number of carefully arranged standards, from which he extracted the last drop of lyricism while draining away any hint of sentimentality, plus a handful of his own compositions, a few of which sounded like standards as soon as he wrote them, and a sprinkling of originals from other jazz composers. The blues was seldom a part of the trio’s programme, at least in its explicit form.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Melody Maker had sent one of its older writers, Laurie Henshaw, to review the opening night, and he had not found it much to his taste. “More sensate than emotive,” was how he described Evans’ approach. “He bends intently over the keyboard pulling close clusters of chords, weaving complex harmonic patterns than can surely be most totally appreciated by the musically literate.”

Even then it was hard to agree, and of course it would be impossible now: there is nothing forbidding about a single bar of the music heard in this recording. (But then the same writer’s review of Monk three weeks earlier – “His relentless unpredictable hammering reminds one of a schizophrenic piano teacher on some strange jazz trip” – prompted one of his MM colleagues to remark that he had just set jazz criticism back 50 years.)

Henshaw also noted that, on the night he attended, one table of punters had to be shushed by their neighbours at regular intervals. That was not unusual at Scott’s, which had become a destination for expense-account businessmen who had no intention of letting the music get in the way of their banter. Such interruptions are entirely absent here, although a police siren can just be heard behind the exposed intro to “Re: Person I Knew”.

The tapes, apparently dating from the last week of the season, were made by a fan with a seat at a front table, using a high-quality portable machine and single microphone, without the knowledge of the musicians or the club; eventually they found their way into the collection of a friend of Evans, who decided, almost 40 years after the pianist’s death, that they should be heard. The sound quality of the instruments is bright and clean, and the balance is better than one would expect from a club recording of the time. It’s rather poignant to hear Scott himself coming on the microphone at the end of a short but exquisite reading of “Goodbye”, the Gordon Jenkins ballad, to encourage applause for the musicians.

By this time Evans’ music had lost the freshness of the original trio; despite their youthful enthusiasm and technical brilliance, Gomez and Morell were providing a certain type of blueprinted accompaniment rather than engaging in a fully participatory creative conversation. But when you hear the pianist uncoil the short preface to “Stella By Starlight”, set the scene for “So What” with a spray of upper-register notes like drops of ice-water, reconfigure a snatch of the melody to lead into “What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life”, or spin the most refined blues phrases over “Our Love Is Here To Stay”, reservations tend to evaporate.