First things first: forget ‘post-rock’. It might be hard to, given this most fluid of genres is having its moment again, thanks to one-hundred on-line “best of post-rock” lists, and the recent publication of Jeanette Leech’s fearless: The Making of Post-Rock, but Bark Psychosis both predate and transcend the often simplistic faux-experiments under its untidy umbrella. On Hex, the only album Bark Psychosis made across their initial, fated run, the group are looking much further afield – here, there are trace elements of holy minimalism, ECM jazz, the fractal jazz-funk of Miles Davis, the sea-spray of Can.

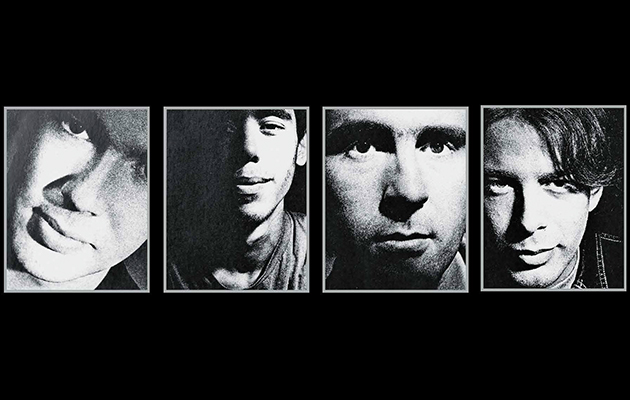

In some ways, it’s a surprise that Bark Psychosis even found their way here. In the late ‘80s, the group, led by teenage friends Graham Sutton and John Ling, were enamoured of the heavy/noisy aesthetic of groups like Swans, Napalm Death and Sonic Youth. They learned, and listened, quickly, though – by their debut single, 1990’s “All Different Things”, they were somewhere else entirely, using soft-loud dynamics to jolt the listener out of their senses, or quietly burbling away in frigid, unsettled ambience. Over three more singles, Bark Psychosis very slowly explored the possibilities in their music: by the time they reached their fourth single, 1992’s startling “Scum”, they simply let everything flow.

“Scum”’s twenty-two minutes lead us, in a roundabout way, into Hex. Tellingly, “Scum” was the first time Bark Psychosis had recorded at St. John’s Church on Stratford Broadway, London, though they’d been rehearsing there for a while. Allowing the song structure to hang loose, its ebbs and flows, its swells and recesses, are chillingly effective, the song often lost in stillness, or folding into silence, the room humming to itself. At the church, they learned the power of acoustics, and Hex would develop, at least in part, in response to “Scum” – instead of “Scum”’s singular mood, Hex would be also recorded in many other spaces, the better to capture their particular aura.

It would also prove to be a protracted and trying recording process that would lead to the group’s disintegration. They may have had the support of a major label in Virgin subsidiary Circa, but every penny would go into recording; by the time they got to RAK Studios to mix the album, they were living out of drummer Mark Simnett’s camper van and scrounging off other groups’ leftovers for food. Was it all worth it? Hex’s delicacy, its confidence, its moments of sheer, unalloyed beauty, balanced by its extended passages of knife-slit tension and fraught anxiety, answer the question with a decisive ‘yes’, even as the album sessions stretched everyone to breaking point.

Hex opens with “The Loom”, a modular piece where a sweet, melancholy piano refrain, curled by purring strings, eases into an elusively gorgeous melody, Sutton singing, ‘I just came to watch you smile’ before a dub-wise bass leads the song into darker terrain: the slow weave of bass, percussion and ghosted drones is the closest Bark Psychosis get to their most obvious precursors, the Talk Talk of Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock. Lead single “A Street Scene” follows, another uncertain construction that orbits a tremolo-ing guitar with all the fragility of a spun sugar nest, sudden bursts of noise jolting the mise en scène before everything winds down to a gentle conclusion, guitar drizzling like Vini Reilly playing at 16RPM. “Absent Friend” and “Big Shot”, the other two songs of the album’s first half, play at similar games – periods of stability spiral into uncertainty; dampened snares tap out unhurried rhythms; sighs score the skyline.

In its second half, Hex turns monumental. “Finger Spit” is rife with lacunae, with great arcs of blasted guitar carving parabolas in the humidity of a late Summer night, Simnett’s drums skittering around the kit as slamming voids of piano crash out of the instrument’s frame. “Eyes & Smiles” is the moment of hope amidst the album’s uncertain tenor, Sutton crying ‘you’ve gotta go on’ as the group builds one of its richest songs, weaving uncommon beauty from more Reilly-esque guitars, while muted brass sings out across plains of ghostly synth.

The comedown is “Pendulum Man”, an instrumental with all the gorgeous calm of Eno’s Music For Airports, its slow clockwork tempo pulsing out a great architectonic space while Bark Psychosis themselves seem slowly to recede, ethering out of earshot. It’s a beautiful, pellucid ending to a monumentally brave album that all but called time on this line-up of Bark Psychosis. Really, where else could they have gone from here?

Q&A

Graham Sutton

What was the goal when you started Hex?

Just to feel fulfilled as a musician. It’s really hard to put yourself back in the mindset of a twenty, twenty-one-year-old. It was really fucking intense, it was so driven.

And Hex is such a self-contained world.

There was a thing of trying to stretch ourselves, or do something new. That time around, we had access to more. Apart from ten days in a proper studio, it was all rented gear that was bolted together, moved to different locations, set up, recorded, patched together. It’s very much a case of DIY.

Can you tell me about those spaces?

We started at Bath Moles, this little studio above a club. Then we moved to the church for six weeks, to try different stuff there. We also moved to different people’s flats and houses, [for example] if they had a piano somewhere, in their front room.

What has the reissue allowed you to do?

The biggest thing is to be able to do it properly, actually going back and managing to source the original tapes and to get those mastered properly.

I wonder whether realising it as close as possible to how you would want, allows you to close the book on it, somehow.

Certainly. It’s been done properly now. That makes me happy.

INTERVIEW: JON DALE