Well, where would you start, given apparently unlimited funds and time, plus the moral support of no less than John Lennon, to tell the entire history of 20th century popular music? Where do you start, and where do you end? In the very first shot in Tony Palmer's colossal documentary series - all five DVDs, 17 episodes, 14 hours and 45 minutes of it - we are accompanying some unseen pop idol inside a limo approaching the Hammersmith Odeon, assailed by a mob of rabid fans. From being inside the eye of this frenzy, Palmer whisks us to an almost prehistoric West Africa, on a musicological search for the fount of blues and rhythm. A scepticism about the traditional view of 'jungle drums' as the source of rock 'n' roll takes him inland to the astringent desert guitars of Mali and Nigeria, observing the music's passage along the slave routes to America and the complicated cultural conveyancing that saw black music hideously hammed up and exploited in Minstrel Shows. We return to Africa for some explosive footage of Fela Kuti, Africa 70 and his exotically dancing wives, plus Ginger Baker trancing out with a roomful of Nigerian drummers. And that's just the first episode. Made in 1975, All You Need Is Love took a long view of 75 years of popular music, observing its mutation from spontaneous folk form to multi-million dollar business and shaper of social forces. There are episodes devoted to Ragtime, Jazz, Blues, Tin Pan Alley, Musicals, Country, Folk and Protest Songs, the coming of Rock 'N' Roll, and on to the electrification of the 60s and 70s. The series is the product of a televisual age when big subjects - Kenneth Clark's Civilisation, Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent Of Man, The World At War - were still granted room to breathe. All You Need Is Love is in the same bracket, a work of anthropology as much as entertainment. Palmer was equally at home in the worlds of Frank Zappa or Gustav Mahler, and while clearly in love with his subject, these films keep their cool in the presence of celebrity, making powerfully rhetorical snips with the editor's scalpel. Footage of Count Basie mugging to camera is intercut with a Ku Klux Klan ceremony; Columbia boss Clive Davis boasts how music has become a bigger sector than movies, his pride undercut by Keith Moon grunting his way through a solo vocal take - shorn of backing track - from Two Sides Of The Moon. You can sense Palmer's efforts to look beyond received wisdom and construct arguments. The episode dealing with The Beatles, for instance, is equally about how the pop marketing machine woke up to what Derek Taylor laconically calls "the longest-running story since the Second World War". Miraculously, the series doesn't feature a narrator; the story unravels via a shrewd shuffling of archive and contemporary film, plus interviews with artists and their makers, bosses, critics, fans. We meet stars who lived through incredible times - Earl 'Fatha' Hines talks of playing for Al Capone; Dizzy Gillespie describes what it was actually like up on the stand with Charlie Parker; Murray The K recalls The Beatles' arrival in the States. Unlike today's typical TV music doc - frustratingly short clips, clichŽ-ridden voiceovers and self-advertisments for Stuart Maconie and Miranda Sawyer - these films kick back and groove on their subjects, letting whole songs play out, interviewees ramble and digress. The camera lingers to register significant places and atmospheres: the Manhattan asylum where Scott Joplin died insane; the Ealing blues club where Alexis Korner found The Rolling Stones rehearsing; the massed potential energy of a stadium rock crowd minutes before showtime. Even the interviews and contemporary material are gorgeously rendered in bronzed, hazy film stock, appropriate given that it was filmed just as pop music's high summer was about to turn to autumn. As Palmer approaches his own present time, the story gets inevitably fragmented. The future, imagined in the final episode, is Tangerine Dream, Muzak, Mike Oldfield, and, er, Black Oak Arkansas. Punk rock is waiting to be born, but Palmer's final image is unwittingly prophetic: Oldfield alone in his private studio composing Ommadawn, the precursor of a thousand bedroom producers of the future. EXTRAS: none. ROB YOUNG

Well, where would you start, given apparently unlimited funds and time, plus the moral support of no less than John Lennon, to tell the entire history of 20th century popular music? Where do you start, and where do you end? In the very first shot in Tony Palmer‘s colossal documentary series – all five DVDs, 17 episodes, 14 hours and 45 minutes of it – we are accompanying some unseen pop idol inside a limo approaching the Hammersmith Odeon, assailed by a mob of rabid fans.

From being inside the eye of this frenzy, Palmer whisks us to an almost prehistoric West Africa, on a musicological search for the fount of blues and rhythm. A scepticism about the traditional view of ‘jungle drums’ as the source of rock ‘n’ roll takes him inland to the astringent desert guitars of Mali and Nigeria, observing the music’s passage along the slave routes to America and the complicated cultural conveyancing that saw black music hideously hammed up and exploited in Minstrel Shows. We return to Africa for some explosive footage of Fela Kuti, Africa 70 and his exotically dancing wives, plus Ginger Baker trancing out with a roomful of Nigerian drummers. And that’s just the first episode.

Made in 1975, All You Need Is Love took a long view of 75 years of popular music, observing its mutation from spontaneous folk form to multi-million dollar business and shaper of social forces. There are episodes devoted to Ragtime, Jazz, Blues, Tin Pan Alley, Musicals, Country, Folk and Protest Songs, the coming of Rock ‘N’ Roll, and on to the electrification of the 60s and 70s. The series is the product of a televisual age when big subjects – Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation, Jacob Bronowski’s The Ascent Of Man, The World At War – were still granted room to breathe.

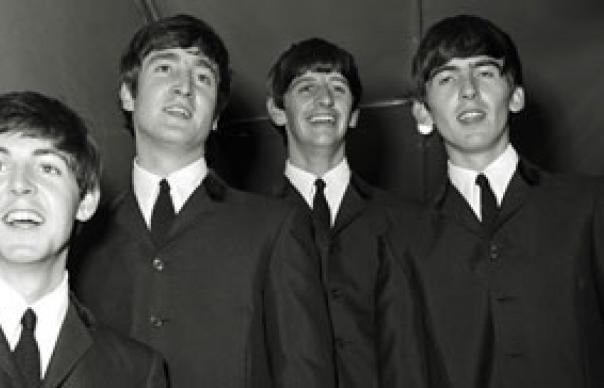

All You Need Is Love is in the same bracket, a work of anthropology as much as entertainment. Palmer was equally at home in the worlds of Frank Zappa or Gustav Mahler, and while clearly in love with his subject, these films keep their cool in the presence of celebrity, making powerfully rhetorical snips with the editor’s scalpel. Footage of Count Basie mugging to camera is intercut with a Ku Klux Klan ceremony; Columbia boss Clive Davis boasts how music has become a bigger sector than movies, his pride undercut by Keith Moon grunting his way through a solo vocal take – shorn of backing track – from Two Sides Of The Moon. You can sense Palmer’s efforts to look beyond received wisdom and construct arguments. The episode dealing with The Beatles, for instance, is equally about how the pop marketing machine woke up to what Derek Taylor laconically calls “the longest-running story since the Second World War”.

Miraculously, the series doesn’t feature a narrator; the story unravels via a shrewd shuffling of archive and contemporary film, plus interviews with artists and their makers, bosses, critics, fans. We meet stars who lived through incredible times – Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines talks of playing for Al Capone; Dizzy Gillespie describes what it was actually like up on the stand with Charlie Parker; Murray The K recalls The Beatles’ arrival in the States.

Unlike today’s typical TV music doc – frustratingly short clips, clichŽ-ridden voiceovers and self-advertisments for Stuart Maconie and Miranda Sawyer – these films kick back and groove on their subjects, letting whole songs play out, interviewees ramble and digress. The camera lingers to register significant places and atmospheres: the Manhattan asylum where Scott Joplin died insane; the Ealing blues club where Alexis Korner found The Rolling Stones rehearsing; the massed potential energy of a stadium rock crowd minutes before showtime.

Even the interviews and contemporary material are gorgeously rendered in bronzed, hazy film stock, appropriate given that it was filmed just as pop music’s high summer was about to turn to autumn. As Palmer approaches his own present time, the story gets inevitably fragmented. The future, imagined in the final episode, is Tangerine Dream, Muzak, Mike Oldfield, and, er, Black Oak Arkansas. Punk rock is waiting to be born, but Palmer’s final image is unwittingly prophetic: Oldfield alone in his private studio composing Ommadawn, the precursor of a thousand bedroom producers of the future.

EXTRAS: none.

ROB YOUNG