When the album and film that shared the title Let It Be appeared in the spring of 1970, they were not greeted with the usual warmth. As the arrival of a new decade consigned the ’60s to history, they seemed an unwanted reminder that an era responsible for so much pleasure had ended badly. It felt like these final Beatle documents had been sanctioned by people who no longer recalled nor cared what had been on their minds when they got together in the film studios at Twickenham at the beginning of the previous year, even then unsure whether they were rehearsing for a stage show or putting together the material for a new album.

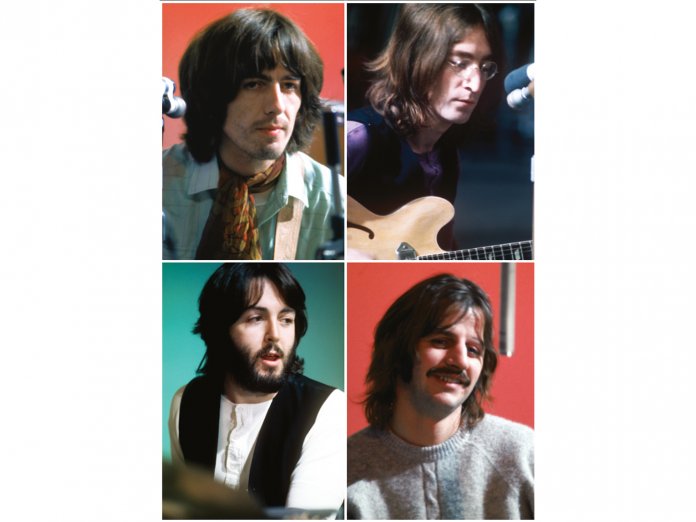

The legend tells us that by the time the sessions for Let It Be began, the Fab Four could no longer stand the sight of each other. It’s certainly true that the claustrophobia of Beatlemania had taken the gloss off the camaraderie forged in Hamburg. But for once a special deluxe edition, with the outtakes and offcuts, does function as a corrective to the historical record.

The premiere of the Let It Be film on May 20, 1970 and the appearance of the accompanying album were shrouded in the acrid smokescreen that by that time enveloped the quartet’s disintegration. Released after the polished Abbey Road, which had been recorded subsequently, these randomly assembled, ill-assorted and largely unloved jottings formed a sour postscript to the most joyous of stories.

A reminder of that original sense of joy came in last Christmas’s five-minute teaser for Peter Jackson’s forthcoming three-part, six-hour Disney+ TV series, based on 56 hours of unused footage shot for the Let It Be movie by the director Michael Lindsay-Hogg at Twickenham and Apple studios. The advance clip shows them seemingly at ease in each other’s company, even relishing it, for all the row that led George Harrison to absent himself for a couple of weeks, the decision to work without George Martin and the tensions created by disputes over how to handle their business and financial affairs after Brian Epstein’s death.

The audio releases preceding Jackson’s film include a remix in stereo, 5.1 surround DTS and Dolby Atmos of the original album by Giles Martin and Sam Okell, who performed the same function in recent years for Sgt Pepper, the White Album and Abbey Road. This is not the Let It Be Naked sanctioned by Paul McCartney that appeared in 2003, but a modern mix that leaves Phil Spector’s influence largely intact, except for a de-emphasis on the classical harp on “The Long And Winding Road” specially requested by the song’s composer.

The package also includes the version of the album submitted in 1969 by Glyn Johns, who engineered the sessions, for potential release under the title “Get Back”, plus 27 tracks from the recording and rehearsal sessions at Twickenham and Savile Row and from the final concert on the Apple roof on January 30, 1969 (the entirety of which, also shot by Lindsay-Hogg, will be featured in one of Jackson’s episodes). There’s a four-track disc recreating The Beatles’ first release in the Soviet Union: “Let It Be”, “Across The Universe” and “I Me Mine”, plus “Don’t Let Me Down”. A 12×12 hardback includes a scene-setting piece by John Harris and a satisfyingly detailed track-by-track analysis by Kevin Howlett.

Available separately from the package of discs is a much chunkier 40-quid coffee-table hardback, The Beatles: Get Back, in which many stills from the sessions and the rooftop concert are accompanied by transcripts, edited by Harris, of the conversations between the members of the group and others as they went about their work. These are culled from 150 hours of the original quarter-inch mono audio tape recorded on a Nagra machine and then stolen, to be recovered by police in the Netherlands about 15 years ago.

Martin and Okell have revitalised the basic album without disturbing its essence, to the extent that Johns’ version – which also includes an oldies medley and “Teddy Boy”, later re-recorded by McCartney for his first solo album – becomes a mere historical curiosity. The new sound is brighter, more alive, more fully dimensional. You probably won’t want to hear Let It Be any other way after this. And you may even conclude that Spector did not, after all, do such a discreditable job on the two songs, “Let It Be” and “The Long And Winding Road”, for which he was been most savagely attacked. It’s interesting to discover from the transcripts of the studio conversations that McCartney had always thought of adding brass and strings to the latter.

As for “Let It Be”, a song with a very complicated recording history, the transcripts reveal that during the fifth day of work at Twickenham on January 8, 1969, it was Harrison who suggested it would be a good song for Aretha Franklin. McCartney’s enthusiastic response led to an acetate being sent to the Queen of Soul, who created a small masterpiece that came out just ahead of The Beatles’ own version.

Listening to the remixes, rehearsals and jams (including a fabulously raw version of “Oh! Darling”, one of several Abbey Road songs which, as Harris points out, took shape during these sessions), it seems clear that the focus was less on the actual music than on negotiating some sort of collective dynamic that might sustain their future. Paul is clearly trying to prod the group into the direction that “Wings” would take, in which “getting back” means piling themselves and the gear into a Transit and driving up to Primrose Hill to play an impromptu gig of basic rock’n’roll. He is encouraged by Lindsay-Hogg, who can see how it might work as a film, but the others have their own opinions, not always coherently expressed.

In addition to “Teddy Boy”, we get glimpses of “All Things Must Pass” and “Gimme Some Truth”, neither of which will have a future on a Beatles record. The inclusion of Billy Preston’s brief rendering of “Without A Song” provides a bracing lift to a different level of musicianship. “I feel much better since Billy came,” Harrison remarks in the January 21 transcript after Lennon has pointedly introduced a passing George Martin to the American pianist as “our A&R man”.

The intimacy of these documents persuades us we’re finding new truths in them. Perhaps we are. But Let It Be – the album, that is, in whatever form – remains a scrapbook of something falling apart, its participants impatient for something new to begin. Even the spontaneous jokes and japes included in Jackson’s teaser are actually being performed by four men familiar since A Hard Day’s Night with the techniques of cinéma vérité and now so used to cameras that they know what to show and what not to show.

“The things that have worked out best ever for us haven’t really been planned any more than this has,” Harrison remarks to Lennon before McCartney arrives at one of the sessions, in a fragment of dialogue included among the outtakes. “You just go for something and it does it itself, whatever it becomes.” How wrong could he have been? It’s as if they needed to misunderstand the past in order to break with it and begin their own future.