On 15 August 1970, The Beach Boys repaired to Brian Wilson’s house in Bel-Air, setting up in the studio downstairs. Sunflower, their new album, was due out in a fortnight, but the band were already sketching ideas for a follow-up. Wilson laid down a basic track for “Til I Die, a song he’d been struggling with for some time but was yet to perfect. Mike Love, meanwhile, unveiled the quietly rapturous Big Sur.

Trailed this June ahead of Feel Flows – a major compilation centred around Sunflower and its 1971 successor, Surf’s Up – Big Sur finds the band in their preferred milieu: hymning the glory of a California that’s part real and part fantasy, where crimson sunsets are followed by dutiful golden dawns and bubbling mountain springs feed inexorably into the ocean. A less mellifluous version of the song would surface as the opening section of Holland’s California Saga in 1973, but the original is far more persuasive. Much bootlegged but widely unavailable until now, its belated appearance teased the possibility of a trove of hidden revelations within The Beach Boys’ catalogue.

Feel Flows makes good on that promise. Produced by Mark Linett and archive manager Alan Boyd – the capable hands who delivered 2011’s The Smile Sessions – it’s a set as vast as it is remarkable, containing no fewer than 135 tracks, 108 of which have never been officially released before. Strung across five CDs are various live cuts, outtakes, demos, alternate mixes and isolated backing tracks that show the full extent of The Beach Boys’ endeavours at a critical point in their history.

The tragedy back then, as the late ’60s gave way to a new decade, was that most people had stopped listening to The Beach Boys. After a string of dismal-selling albums, Capitol showed no interest in extending their contract beyond 1969. And Jimi Hendrix’s tart assessment of the band as a “psychedelic barbershop quartet” confirmed the suspicion – certainly among those who still only equated The Beach Boys with sand, sun and breakers – that they just weren’t made for these heavier, more socio-political times.

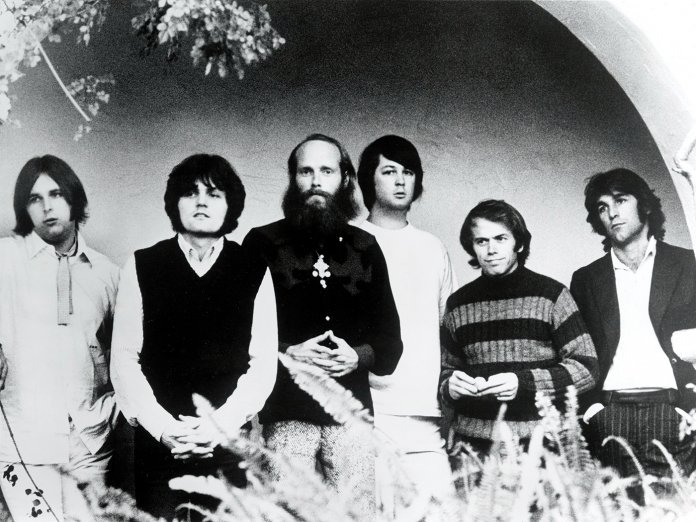

Released with the full co-operation of the surviving members, Feel Flows attempts to finally lay waste a tired myth. The Beach Boys were brimming with ideas for Sunflower, each member spurred by a new sense of artistic liberation. Brian Wilson was slowly returning to action after the psychic collapse that followed the aborted Smile sessions, though he would never again be the dominant force that had captained Pet Sounds. “Brian probably knew he couldn’t make a whole album at that point,” says Bruce Johnston in Howie Edelson’s comprehensive liner notes for Feel Flows. “So we got the best out of Brian and also discovered the other guys in the band could write. And it was interesting. It had a lot of textures as far as the songs, the voices, the leads.”

Rooted in remastered versions of Sunflower and Surf’s Up, Feel Flows stakes a number of claims. The accompanying live tracks prove that, at their best, The Beach Boys could be a pretty formidable rock’n’roll band, an attribute not always given its rightful acknowledgement. Carl leads the charge on a heroically vigorous It’s About Time, from 1971, flanked by fat horns and whirling organ. The same applies to Al Jardine’s Susie Cincinnati, recorded at an Anaheim show in 1976 during the Brian’s Back! campaign, marking the eldest Wilson’s return to the live stage. Meanwhile, a 1972 rendition of Long Promised Road is nothing short of majestic, as is a Carl-steered Surf’s Up, which sacrifices some of Brian’s studio delicacy for a jazzier kind of ebb and flow. Carl’s creative awakening is a key aspect of Feel Flows, beginning with Long Promised Road and the title track, both written with Beach Boys manager Jack Rieley. He emerges as a fine musician too, but it’s his capacity as an arranger and producer that guides the band’s aesthetic. Brian had a point when he called the youngest Wilson brother “the spirit of The Beach Boys”.

That said, it’s Dennis Wilson who reveals himself as arguably the true star of Feel Flows. Having partially filled the Brian void on 1969’s 20/20, Sunflower saw him reconcile the twin poles of his songwriting with the vivaciously rocking Slip On Through and the sensitive Forever. Here, on disc five, are the gorgeous remnants of a lost solo project, tentatively titled Poops/Hubba Bubba. Co-written in 1971 with Daryl Dragon, later to find fame as one half of Captain & Tennille, Dennis’s songs achieve a new kind of elevation. Behold The Night is a harpsichord ballad pitched between anguish and longing, all the more striking for its understated elegance. Old Movie (Cuddle Up) was revamped for the following year’s Carl And The Passions – So Tough, but is much more effective as a wordless chorale, joined by the similarly blissful Hawaiian Dream. But it’s the crystalline, piano-led Medley: All Of My Love / Ecology and Before (the latter punctured by distorted guitar) that signify his unbound talent, both serving to foreshadow the wounded, soulful beauty of 1977’s Pacific Ocean Blue, Dennis’s solo debut.

Unsurprisingly, given its sheer size, Feel Flows also makes room for a fair share of curiosities. Disc two closes with a cloying cover of Seasons In The Sun, produced by Al Jardine and Terry Jacks at Brian’s house in the summer of 1970. Never mind that Jacks would turn it into a huge solo hit a few years down the line. Here, sequenced together with Love’s Big Sur and Dennis’s Sound Of Free, it feels like The Beach Boys are merely slumming it.

The decidedly odd My Solution, also from the Surf’s Up sessions, makes its bow too. Recorded on Halloween night, it finds Brian going full Vincent Price, playing the mad scientist over descending chords and various sound effects. Sweet And Bitter, sung by Mike Love, is more intriguing but equally strange, essentially a healthy living manual with a jokey plug for the Radiant Radish, Brian’s short-lived grocery store in West Hollywood.

A good portion of discs three and four are taken up with in-progress backing tracks and a cappella cuts from the Sunflower and Surf’s Up sessions. And while this is hardly a new tactic for Beach Boys compilers, it does at least underscore how the rich complexity of the syncopated vocal arrangements were such an integral part of the band’s identity. More directly engaging are the alternative takes. A stretched-out version of the august “Til I Die, with a lingering bass and vibraphone intro, attempts to inject Brian’s existential crisis with a misplaced feelgood factor. No longer is he lost on the ocean or perishing in a valley. Instead, he declares, “I found my way”. By contrast, a sparser take on Surf’s Up (only one of several variants on offer throughout) only accentuates its allusive vulnerability.

Feel Flows is emphatic proof that The Beach Boys never stopped making sublime, artful, spiritually invested music, no matter how far they’d fallen in popular opinion. Post-Pet Sounds, the incentive, as Al Jardine observes, was “to find a way to move on beyond Good Vibrations. That was the pinnacle.” In that context, Sunflower and Surf’s Up represent their second great peak.