The deaths of Scott Walker and Mark Hollis so close together feels like particularly cruel timing. Both remarkable musicians who followed their own paths away from the mainstream, where they flourished, astonishingly, entirely on their own terms. We've been played a lot of Scott since yesterday's ne...

The deaths of Scott Walker and Mark Hollis so close together feels like particularly cruel timing. Both remarkable musicians who followed their own paths away from the mainstream, where they flourished, astonishingly, entirely on their own terms. We’ve been played a lot of Scott since yesterday’s news – we’re listening again to Nite Flights as I write this – and what’s evident as we join the dots from the Walker Brothers’ heyday through to those later solo albums, is how few musicians went the artistic distance that Walker did. The Guardian have published a series of tributes to Walker from other musicians – you can read it here – where, among them, Bill Callahan articulates better than anyone I’ve read so far Walker’s peerless musical journey. “It’s the kind of trajectory we can all only wish for – moving closer and closer to the rush of the waterfall until you see every tiny drop of mist as large as the galaxy. He was the definition of uncompromising. with himself, his art, the world.” There’ll be a substantial tribute to Walker in the next issue of Uncut.

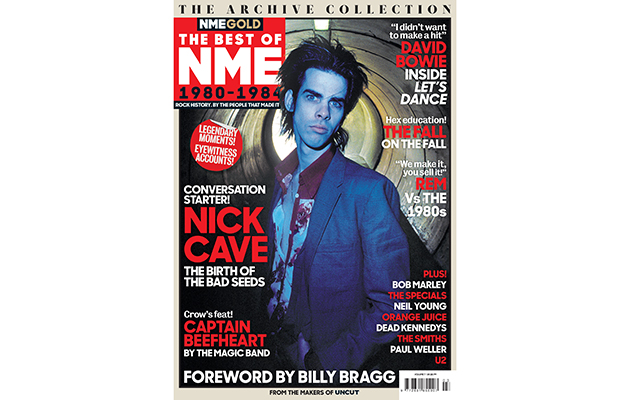

Apologies for the rather uncouth jump, but among more positive news I’m delighted to introduce the latest member of the Uncut family. This is NME Gold 1980 – 1984 – which is in shops from Friday but available now from our online store. As usual, this rounds up the very best archival pieces alongside new interviews and a bespoke introduction from Billy Bragg. Here’s an except, where the Bard of Barking shares his views on his first couple of albums…

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

“With my first album Life’s A Riot… I was trying to create a utilitarian ideal of what pop music could be. After punk, the industry had got control again – it was more about the looks than the anger, and I was trying to be outside of it. Life’s a Riot… had originally been made as publisher’s demos, so going in and making a second album, Brewing Up With Billy Bragg, had a little bit more thought about it. Talking With The Taxman About Poetry was the difficult third album, you need to move your idea forward, but with Brewing Up… people were still interested in what I was doing. With the second album you don’t necessarily need to show where you’re gonna go, you just need to show you’ve got more songs. So I didn’t need to come in with the full band and go for pop glory and stardom. There was no single from the record so I was still trying to hold on to the punk ethic.

“There was political stuff going on around the Right To Work march and opposition to Thatcherism and the riot in ’81, but it was fragmented. It took the miner’s strike in ‘84 to be the catalyst for political pop of the 1980s. As a political singer I was out on a limb – that was my whole schtick – but I found there were a bunch of people who were interested in music that was about something. They’ll always be a minority, but a significant minority, enough to sustain a career. I was able to get a reputation as someone who had something to say. I was a continuity Clash, you could call me – the link between what The Specials and Two-Tone were doing and the music that responded to Thatcherism. The miner’s strike is what brings the music I was making into the mainstream.

“I sang ‘I don’t want to change the world’ as a kind of ironic statement. It came after punk, which had been all about changing the world and it was my way of saying it’s all well and good all that stuff, but you still occasionally need a cuddle from someone. Ever since, that’s been the nexus of my songwriting: hard politics and vulnerable emotions.”

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!