After we had to rent our own theatre to get a gig, we started talking about where there was to play. There wasn’t anywhere.

Tom lived on the Lower East Side, which meant, when he walked to rehearsals in Chinatown, he walked down the Bowery. Now, the Bowery had a reputation, but it was not dangerous. It was just full of drunkards. You could step over them on the street. And had to.

One day, Tom came in and said, “I might have found a place. On the Bowery. It’s a dive.”

That’s what we needed. A dive. Somewhere nobody else wanted to play, where we could move in and take over. Tom said he had seen a guy outside this place, working on the front. He and I went back to talk to him. We saw the owner, a man called Hilly Kristal, on a stepladder, fixing up this awning: CBGB OMFUG [Country Bluegrass Blues – Other Music For Uplifting Gormandizers]. We looked up at him: “You gonna have live music?”

We played our first gig at CBGB the last Sunday of March. Sundays were Hilly’s worst nights. Terry convinced him to let us play by guaranteeing he’d fill the place with friends who were all alcoholics. So Hilly gave us four Sundays in a row. Pretty soon, other bands started hearing about it, and coming down asking for gigs. Hilly didn’t know anything about rock music. Basically, we steamrollered him. Terry offered to start booking the club, so long as it was understood it was Television’s place. Bands would audition, and Terry would ask me what I thought. Talking Heads, the Ramones, Blondie: that’s how they started playing CBGB. We were picking the bands and playing, and it was like hosting a three-and-a-half-year-long New Year’s Eve party. Once we got some steam, CBGB was It.

Sure, it was a dive. It was difficult to get people in suits down there, or even the older generation from Max’s. We were like hobos to them. But there was almost a glamour to the poverty. Nobody had done that before. Up ’til then, in rock’n’roll, everybody wanted the finest shoes. Everybody was chasing this glamorous high-life.

We weren’t. When you hear bands say they don’t care about anything? I guarantee you: they do. We were probably the closest to a band that really didn’t care.

CBGB was taking off. Labels were showing interest. Late in 1974, Richard Williams from Island wanted us to go into the studio with him to make a demo, but said, “I don’t know much about a studio. Can I bring a guy to help? His name is Brian Eno.”

Eno came in with all these whacked ideas. “Let’s glue the amplifiers to the ceiling.” “Let’s cut up the lyrics and throw them in the air.” We weren’t having any of it.

We did six songs. Hell was upset because he only got one of his songs on the tape, while Tom got five. Richard got scorched. Tom was beginning to push him out.

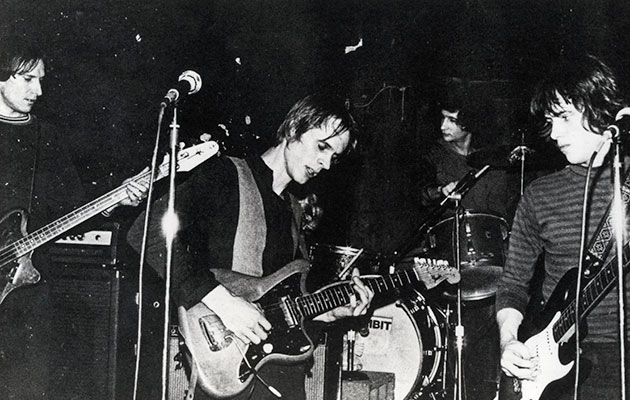

From the very beginning, when we played live, Tom was on at Richard to “stop moving”. He said it was distracting him, and it looked “artificial”. It used to be that I stood in the middle of Richard and Tom onstage. I was the George, with the John and the Paul either side. Then Tom suddenly decided he wanted to be in the middle.

That was the beginning of the end of the first Television: the Television that was sloppy, punk-ass, and a mess; but also extremely exciting. That band was like being in a circus. You never knew what was going to happen. A train wreck, sure, but fun.

It was driving Tom nuts, though. Tom was a control freak when it came to music. Without a solid bass player, especially with Billy being nuts all the time on drums, there was no grounding, no solid bottom. Tom was beginning to talk about replacing Hell, but Richard quit. I almost quit myself, because I thought, without Richard, the fun was gone. However, Tom asked Fred Smith to leave Blondie and join us, and asked me: “Come on. Just come play.”

Within 10 minutes, I had to admit it. Fred was keeping down the tempo, which meant Billy could go crazy nuts, but we still sounded like a band. Television suddenly made sense.