It is 1977, and Ian Brown has just met the soulmate who will become his closest friend and, in time, worst enemy. John Squire, the taciturn and introspective mirror to Brown’s bolshie livewire, lives on the same street in the leafy south Manchester suburb of Timperley – Sylvan Avenue. Bright young kids from working-class homes, sticking out like sore thumbs at the largely middle-class Altrincham Grammar School.

Squire recalls their first encounter differently, meeting Brown as a naked toddler in a sandpit. But Brown’s first memory is of defending his teenage neighbour from a vicious beating at school. Already a keen karate student, his reputation as a classroom psycho acts like a protective force field. The other schoolkids nickname him Bruce Lee, his childhood hero.

Brown and Squire instantly bond over punk and politics. In the passionately socialist Brown household, the Black Panthers are heroes and the Royal Family parasites. Leaving school to drift into aborted college careers, dole and dead-end jobs, he and Squire form their first band, The Patrol. They also join the Socialist Workers Party, selling papers and collecting money for the miners.

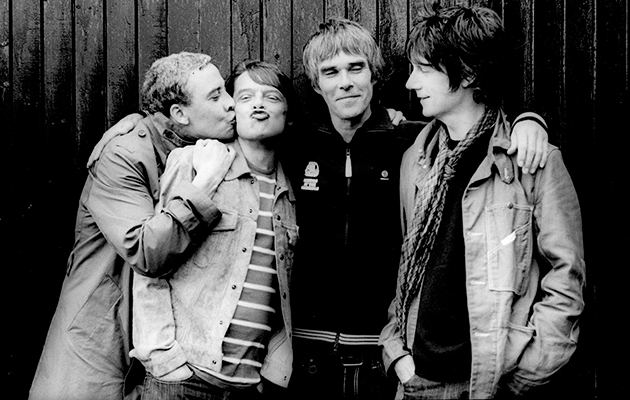

In 1984, The Patrol evolve into The Stones Roses, with Alan “Reni” Wren on drums and Gary “Mani” Mounfield on bass. By 1986, they convince themselves they are better than The Beatles. All they need to do now is persuade the rest of the world.

When the Roses broke through, did you consider yourselves heirs to Manchester legends like Joy Division and The Smiths?

“We didn’t, because to us Manchester had always been perceived as miserable. I see The Stone Roses in ’89 as Technicolor; we were all about joy and possibilities of life. The Smiths were a bedsit mentality. Our attitude was to get out of that, be exciting, not dour and grey. We did like Joy Division and New Order, but we definitely didn’t take off any of the Manchester groups.”

Who did you see as competition, then? The Beatles?

“We did a 16-track demo in ’86 in Peter Hook’s studio which we thought was as good as The Beatles. We thought if we’d had six months with George Martin in Abbey Road we’d sound as good as them. But now when I see that they vote the Roses No 1 or No 2, I think absolutely no way did we get near the best five Beatles LPs. I have arguments with people who say we were better than the Pistols and The Clash. Maybe we were their Beatles, their Sex Pistols. But to me, we never touched the Pistols, Clash, Beatles or Rolling Stones.”

Is it true you never made a penny from the first Stone Roses album?

“That’s right. We did a deal in 2003 with the Roses’ greatest hits, which means we now get paid for that first LP, but only on sales since 2003. I think we got 25 grand each. I don’t know how much we should have made, but I hear it’s sold three million, so that should be five million quid between all of us.”

You made no money from Spike Island or Alexandra Palace either?

“When we did Alexandra Palace in ’89, they said we could have three nights. We said no, we just wanted to hit it and pull out. We could have made 150 grand a night, but that didn’t matter, because our faith at that time was we were going to make 10 LPs and end up with more than we knew what to do with anyway. We were only on 60 quid a week around ‘Fool’s Gold’ time. Then we put ourselves up to 100 quid a week in ’91, because we wanted to stay hungry.”

You always rate “Fool’s Gold” as the pinnacle, the path the Roses should have taken. Is the lyric based on The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre?

“It is, yeah. About how poor men will all stick together, and then as soon as they get a bit of money they all turn on each other.”

Kind of prophetic, then?

“It did turn out like that, yeah. Heh heh!”