In the summer of 1967, having deferred his entry to Cambridge University, Nick Drake was notionally enrolled at a college in Aix-en-Provence. His real course of study, however, was taking place on the guitar. Having mastered the fleet licks he heard on the first Bert Jansch album (Jansch’s “Strolling Down The Highway” was a staple of his busking sets there), Drake was developing his technique and embarking on his own first compositions.

“He didn’t have any problem busking,” says Robin Frederick, a songwriter who knew Drake in Aix. “He could dazzle on guitar. He knew he was good – he spent a long time getting good. It was positive feedback for him – and a way to get a few francs to go over to Les Deux Garçons and have something to eat. That for him was a fun part of life.”

Although reserved, the possibility of a musical connection could bring Drake out of his shell. Later that summer, in Morocco, it’s said Drake played for several Rolling Stones after chancing on them in a café. As Robert Kirby told it, there was never any intermediary to introduce the pair of them that autumn in Cambridge – Drake simply turned up on Kirby’s college staircase one day and proposed they work together. In Aix, after one of her sets at a café/nightspot called De La Tartaine, Drake now suggested something similar to Robin Frederick.

“He didn’t talk, but it didn’t seem odd to me,” says Frederick. “He could communicate so fluently with music. It was easier for him.”

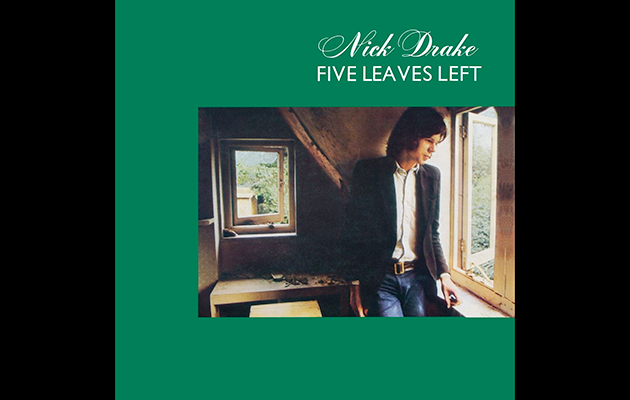

In Drake’s earliest songs, written in Aix, Frederick can hear the seed of what, by Five Leaves Left, had become his unique musical signature. Rather in contrast to the Aix vibe – young people carrying guitars; rapt “circles of lads” listening at Drake’s feet; what Frederick calls the city’s “troubadour-infused ancientness” – Drake arrived at something absolutely antithetical to stoned and hopeful guitar composition.

“It’s a very conscious experimentation with how song melodies and chords work together,” she explains. “He was picking up Bert Jansch and John Renbourn in quite an analytical way. He had steeped himself in bossa nova: the Getz/Gilberto album was huge, we all had it. From bossa nova he picked up a new kind of melody singing.

“If you listen to ‘They’re Leaving Me Behind’, one of his earliest songs, he’s keeping a steady beat on the guitar and then he sings this long melody line over the top of it,” Frederick says. “It was not like anyone else would sing. He had a background as a sax player, and it’s a sax line. If you listen to a song like “All Blues” from Kind Of Blue by Miles Davis – it’s like that.

“By the time of ‘Cello Song’ he’s now developing it as a singer,” says Frederick. “He got the idea of disconnecting the melody from the underlying beat. He’ll start on an unexpected beat in the middle of the bar: you as the listener are being rocked back and forth. It sounds like it’s floating but it isn’t. It’s completely connected.”

In talking about Nick Drake’s sound, Robin Frederick uses words like “complex” and “ambivalent”. His music was built using cluster chords, in which additional dissonant notes are introduced: they add sweet and sour nuance, as dissenting voices might add interest to a story.

“You really hear that on Five Leaves Left,” says Frederick. “On ‘They’re Leaving Me Behind’ he’s struggling for his signature sound. But within 18 months he’s writing ‘River Man’, with these chords, full of light and darkness. Over that he lays the melody which sheds new light on the chords – and he’s doing that in 5/4 time. It sounds like it’s pulling you forward. It’s like overlapping waves.”