All Leonard Cohen wants for his 80th birthday is a cigarette. He smoked, he estimates, for around 50 years, before he gave up a decade or so ago. “I think a lot about smoking,” he reflects. “I’m thinking about it right now.” The smokes aside, Cohen reckons there is unlikely to be a more formal celebration to mark his passage into his ninth decade. “One of the lovely and charitable realities of my family life is we hardly celebrate holidays or birthday or anniversaries,” he confides. “So everybody is let off the hook, if you forget somebody’s birthday or anniversary. There’s no penalties. I think it’ll just go by like any other day. I might have a smoke.” This evening, Cohen is wearing a charcoal grey suit, a light grey shirt and a red and grey striped tie – the same outfit he wears, in fact, on the sleeve of his new album, Popular Problems. He is discussing smoking – among many other topics – in the prestigious surroundings of the Canadian High Commission on London’s Grosvenor Square. It’s a bespoke event to launch Popular Problems: there is a playback, followed by a Q&A hosted by broadcaster Stuart Maconie during which Cohen fields questions from journalists assembled from 25 countries. The most extraordinary of which was posed by a Spanish journalist, who inquired as to Cohen's views on the imminent referendum on Scottish independence... Cohen has done this kind of thing before, of course, most recently at the Canadian Consulate in Los Angeles a few days ago. Back in January 2012, he presented Old Ideas at London’s May Fair Hotel to an invited audience, with Jarvis Cocker acting as host. In fact, Cocker is also here tonight to witness Cohen in action. Needless to say, it’s a remarkable performance. Cohen’s wit is dry and as sharp as you’d hope. Asked, for instance, to comment on his legendary status, he admits, “Sometimes I feel like an institution. Kinda like a mental hospital.” Or when Maconie pushes him for details on his next album, a follow-up to Popular Problems, Cohen claims, “The next record is going to be called Unpopular Solutions.” It’s not all laughs and banter, though. It’s fascinating to watch Cohen as he graciously bats away certain questions – especially those that concern the methods of songwriting – with a one-line reply. “It’s a mysterious process, I don’t really know much about it,” he demures. Asked about the tone of Popular Problems, Cohen offers: “It has a mood of despair. I think it has a unifying feel that, those are things that we award, that we ascribe to a piece of work after it’s finished. While it’s going on, we’re scraping the bottom of the barrel trying to get something together.” It’s a curious reply that almost addresses the songwriting processes, but then assumes a self-deprecatory tone; it becomes a familiar response pattern from Cohen as the 30-minute Q&A progresses. Occasionally, Cohen goes some way to illuminate his creative processes. Asked about the satisfaction of finishing an album, he replies, “I don’t know how other writers feel, but I have a sense of gratitude that you can bring anything to completion in this vale of tears. So it’s the doneness of the thing that I really cherish.” He quotes WH Auden – “A poem is never finished, it’s just abandoned” – before, once again, deflecting so as not to reveal too much information about his craft: “These are technical questions that I don’t think anybody really has the answer to.” Some of this, you suspect, is a necessary part of sustaining a carefully and elegantly cultivated mystique. He will not be drawn, for instance, on politics – either in personal terms (“I’ve tried over the years to define a political position that no one can decipher”) or with regards Popular Problems. “I think it reflects the world that we live in. it wasn’t anything deliberate, but one picks up these things from the atmosphere.” There are strong, but very general, observations about his nationality, for instance: “Canadians are very involved in their country. We grow up on the edge of America. We watch America the way that women watch men. Very carefully. So when there is this continual cultural and political challenge right on the edge of your lives, of course it makes you develop a sense of solidarity. So, yes, it is a very important element in my life.” He will speak, too, at length about finding relevance in songs he wrote four decades ago: “I don’t have any problem with that. Somehow the challenge of a concert, of a song, it is what one is doing which is to find meaning. We are all involved in the struggle at any moment, because we lead the same lives over and over again. It always is the problem of making it new, and making it significant. It’s the same struggle that we have in our daily lives, in our relationships with people that we know very well. You just have to find a way into the centre of the song.” There are moments, though, when he speaks candidly about his philosophies. Asked, for example, about the ‘Manual for Living With Defeat’ that he mentions on “Going Home” from Old Ideas, he begins “I wish I could really come up with something, because we are all living with defeat and with failure and disappointment and with bewilderment. We all are living with these dark forces that modify our lives. I think the manual for living with defeat is to first of all acknowledge the fact that everyone suffers, that everyone is engaged in a mighty struggle for self-respect and significance. I think the first step would be to recognize that your struggle is the same as everyone else’s struggle. Your suffering is the same as everyone else’s suffering. I think that’s the beginning of a responsible life. Otherwise, you’re in a continual battle, savage battle with each other, unless we recognize that each of us suffers in the same way there is no possible solution: political, social or spiritual. That would be the beginning – the recognition that we all suffer.” It’s moments like these, where Cohen allows us a glimpse into his thought processes, that are effectively more rewarding than the witty bon mots. There are, though, plenty of those on offer this evening. On touring, for instance, Cohen admits, “I like life on the road. It’s a lot easier than civilian life. You feel like you’re in a motorcycle gang.” And on the nature of performance itself, he explains, “If you can do anything, it’s kind of satisfying. It’s this and washing dishes that are the only things I know.” But perhaps the biggest laugh comes towards the end. When asked if Popular Problems contained any traces of optimism, Cohen’s reply is faultless and delivered with the kind of impeccable timing that would make a stand-up comedian envious: “I’m a closest optimist,” he deadpans. Popular Problems is released on September 22

All Leonard Cohen wants for his 80th birthday is a cigarette. He smoked, he estimates, for around 50 years, before he gave up a decade or so ago. “I think a lot about smoking,” he reflects. “I’m thinking about it right now.”

The smokes aside, Cohen reckons there is unlikely to be a more formal celebration to mark his passage into his ninth decade. “One of the lovely and charitable realities of my family life is we hardly celebrate holidays or birthday or anniversaries,” he confides. “So everybody is let off the hook, if you forget somebody’s birthday or anniversary. There’s no penalties. I think it’ll just go by like any other day. I might have a smoke.”

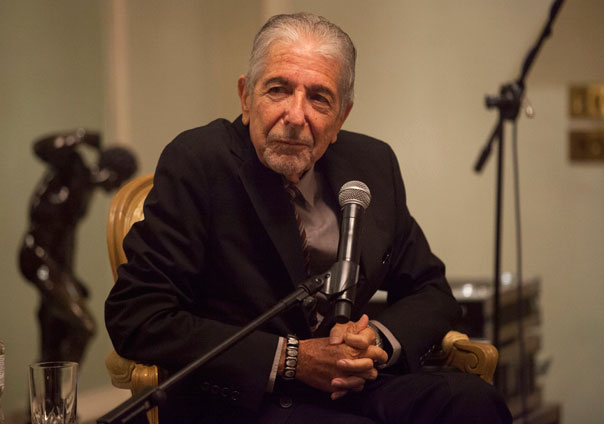

This evening, Cohen is wearing a charcoal grey suit, a light grey shirt and a red and grey striped tie – the same outfit he wears, in fact, on the sleeve of his new album, Popular Problems. He is discussing smoking – among many other topics – in the prestigious surroundings of the Canadian High Commission on London’s Grosvenor Square. It’s a bespoke event to launch Popular Problems: there is a playback, followed by a Q&A hosted by broadcaster Stuart Maconie during which Cohen fields questions from journalists assembled from 25 countries. The most extraordinary of which was posed by a Spanish journalist, who inquired as to Cohen’s views on the imminent referendum on Scottish independence…

Cohen has done this kind of thing before, of course, most recently at the Canadian Consulate in Los Angeles a few days ago. Back in January 2012, he presented Old Ideas at London’s May Fair Hotel to an invited audience, with Jarvis Cocker acting as host. In fact, Cocker is also here tonight to witness Cohen in action. Needless to say, it’s a remarkable performance. Cohen’s wit is dry and as sharp as you’d hope. Asked, for instance, to comment on his legendary status, he admits, “Sometimes I feel like an institution. Kinda like a mental hospital.” Or when Maconie pushes him for details on his next album, a follow-up to Popular Problems, Cohen claims, “The next record is going to be called Unpopular Solutions.”

It’s not all laughs and banter, though. It’s fascinating to watch Cohen as he graciously bats away certain questions – especially those that concern the methods of songwriting – with a one-line reply. “It’s a mysterious process, I don’t really know much about it,” he demures. Asked about the tone of Popular Problems, Cohen offers: “It has a mood of despair. I think it has a unifying feel that, those are things that we award, that we ascribe to a piece of work after it’s finished. While it’s going on, we’re scraping the bottom of the barrel trying to get something together.” It’s a curious reply that almost addresses the songwriting processes, but then assumes a self-deprecatory tone; it becomes a familiar response pattern from Cohen as the 30-minute Q&A progresses.

Occasionally, Cohen goes some way to illuminate his creative processes. Asked about the satisfaction of finishing an album, he replies, “I don’t know how other writers feel, but I have a sense of gratitude that you can bring anything to completion in this vale of tears. So it’s the doneness of the thing that I really cherish.” He quotes WH Auden – “A poem is never finished, it’s just abandoned” – before, once again, deflecting so as not to reveal too much information about his craft: “These are technical questions that I don’t think anybody really has the answer to.”

Some of this, you suspect, is a necessary part of sustaining a carefully and elegantly cultivated mystique. He will not be drawn, for instance, on politics – either in personal terms (“I’ve tried over the years to define a political position that no one can decipher”) or with regards Popular Problems. “I think it reflects the world that we live in. it wasn’t anything deliberate, but one picks up these things from the atmosphere.” There are strong, but very general, observations about his nationality, for instance: “Canadians are very involved in their country. We grow up on the edge of America. We watch America the way that women watch men. Very carefully. So when there is this continual cultural and political challenge right on the edge of your lives, of course it makes you develop a sense of solidarity. So, yes, it is a very important element in my life.” He will speak, too, at length about finding relevance in songs he wrote four decades ago: “I don’t have any problem with that. Somehow the challenge of a concert, of a song, it is what one is doing which is to find meaning. We are all involved in the struggle at any moment, because we lead the same lives over and over again. It always is the problem of making it new, and making it significant. It’s the same struggle that we have in our daily lives, in our relationships with people that we know very well. You just have to find a way into the centre of the song.”

There are moments, though, when he speaks candidly about his philosophies. Asked, for example, about the ‘Manual for Living With Defeat’ that he mentions on “Going Home” from Old Ideas, he begins “I wish I could really come up with something, because we are all living with defeat and with failure and disappointment and with bewilderment. We all are living with these dark forces that modify our lives. I think the manual for living with defeat is to first of all acknowledge the fact that everyone suffers, that everyone is engaged in a mighty struggle for self-respect and significance. I think the first step would be to recognize that your struggle is the same as everyone else’s struggle. Your suffering is the same as everyone else’s suffering. I think that’s the beginning of a responsible life. Otherwise, you’re in a continual battle, savage battle with each other, unless we recognize that each of us suffers in the same way there is no possible solution: political, social or spiritual. That would be the beginning – the recognition that we all suffer.”

It’s moments like these, where Cohen allows us a glimpse into his thought processes, that are effectively more rewarding than the witty bon mots. There are, though, plenty of those on offer this evening. On touring, for instance, Cohen admits, “I like life on the road. It’s a lot easier than civilian life. You feel like you’re in a motorcycle gang.” And on the nature of performance itself, he explains, “If you can do anything, it’s kind of satisfying. It’s this and washing dishes that are the only things I know.”

But perhaps the biggest laugh comes towards the end. When asked if Popular Problems contained any traces of optimism, Cohen’s reply is faultless and delivered with the kind of impeccable timing that would make a stand-up comedian envious: “I’m a closest optimist,” he deadpans.

Popular Problems is released on September 22