Last night [July 16], the BBC pulled a documentary about last summer’s riots just hours before transmission after a court ruling prevented it from being broadcast. It’s foolish, of course, to speculate who initiated proceedings and for what purpose - although at the risk of sounding paranoid, you suspect there’s plenty of people who’d rather not have such pesky reminders of the riots on our screens in the run up to the Olympics. Footage from the London riots feature in London - The Modern Babylon, Julien Temple’s extraordinary trawl through the British Film Institute’s archives. Temple’s old partner in crime, Malcolm McLaren, in a 1991 interview, talks about “the London Mob” as a critical presence in the city’s history, one aspect of a continuous cycle of creation, destruction and rebirth that defines London. A very specific sense of time and place has always been crucial to Julien Temple’s films. It could be that period on the brink of the 1960s, before The Beatles and the Stones, in Absolute Beginners; or the mid-Seventies of The Filth And The Fury – “peeling, crumbling, falling apart” – or perhaps even Canvey Island in the Fifties and Glastonbury in the 1980s. But for London - The Modern Babylon, Temple has a more ambitious reach: his plan is to cover not just one specific time period, but an entire century, give or take, of London life, beginning with the earliest filmed footage of the capital and running up to the present day. The one through-line is Hetty Bower, a sprightly 106 year-old Hackney resident who remembers when going to watch Tower Bridge opening and closing “was an outing”. Nearly nine when World War I broke out, she recalls cheering soldiers "at Dalston Junction, going off in uniform, and we waved. And then I didn’t like what I saw when they started coming back.” A veteran of the 1936 Battle of Cable Street – “Mosley and his followers did not pass” – of today’s Occupy movement, she notes, “They’re asking for the basis of our society to be questioned, and I think that is correct.” Temple’s other interviewees range from Tony Benn to Ray Davies and Michael Horovitz (seen here both in footage from the International Poetry Incarnation at the Albert Hall in 1965 and in the present day), along side everyday Londoners, whose stories and memories provide a satisfyingly intimate element to the film's powerful narrative sweep. Temple’s piece is essentially a document of social transformation. From the British Empire at its peak, with Queen Victoria “opening her doors” to Jewish immigrants in the early 1900s, through Windrush up to the Eastern European influx of today, it’s part of what Suggs describes as “a process. People get taken in and become part of the city itself and change the city. And that’s the whole point. The place keeps changing.” Some things, however, remain sadly the same. Tony Benn tells how “when I was very young, we were taught at school there were only two kinds of people in the world: the British and foreigners. And there were an awful lot of foreigners.” A Jamaican interviewee remembers how his 11-Plus exam “was given to another [white] guy. I found out later from other black guys I know that the same things happened to them.” In archive film, one white resident of Southall, home to a large South Asian community, says, “There’s nothing left in this town any more for English people.” One man, in footage from the 1970s, talks in chillingly reasonable tones about “the National Socialist way.” But it’s not just immigrants who are repeatedly subjected to prejudice. Another thread in Temple’s film are the privations experienced by the working classes through the century, from the Victorian era to the property boom in the 1960s and again in the Eighties, as the docks were run down and eventually the land sold off to developers. “People feel that they’re being excluded from what many of us regard as our river,” says one East Ender, standing outside the entrance to a Thames-side gated community. One prescient scene from The Long Good Friday imagines a UK Olympic bid for the derelict Docklands area. Tracing London’s history chronologically through exhaustively researched newsreel footage, contemporary interviews, songs and movies, Temple’s film is an impressive contribution to the already considerable body of work dedicated to mapping London. As you’d expect, this being Temple it’s not some dry academic work. Temple himself presides over the film as it unspools on multiple TV screens in a CCTV control centre. Black and white footage of horseguards riding through an Edwardian smog is cut to Underworld’s “Born Slippy”; scenes from Tony Hancock’s The Rebel are elided with film of – God! – Quentin Crisp posing for a life-drawing class in his underpants. The material from the Sixties – “the rebellion of the longhairs”, Pink Floyd at the UFO, the Grosvenor Square anti-war march, Twiggy, Terrence Stamp, the Stones in their pomp – is familiar but exhilaratingly cut by Temple, reminding me of the breathless editing of Beatles’ footage in Martin Scorsese’s George Harrison documentary. Temple sees London as a palimpsest, with layers of collective memory built up over time: images of a hippie girl in the 1960s handing out flowers to bemused commuters at Bond Street tube station are cut into film of a Victorian East End flower girl; film of protesting suffragettes is cut to X-Ray Specs’ “Oh Bondage! Up Yours”. 1920s debutantes, hippies, punks, New Romantics have all had their moment of glory in London’s history. “The good old days?” Says Suggs towards the end of Temple’s film. “There were no good old days. London doesn’t belong to anyone. It’s whoever’s on the go at any given moment. London - The Modern Babylon will be released in the UK on August 3

Last night [July 16], the BBC pulled a documentary about last summer’s riots just hours before transmission after a court ruling prevented it from being broadcast. It’s foolish, of course, to speculate who initiated proceedings and for what purpose – although at the risk of sounding paranoid, you suspect there’s plenty of people who’d rather not have such pesky reminders of the riots on our screens in the run up to the Olympics. Footage from the London riots feature in London – The Modern Babylon, Julien Temple’s extraordinary trawl through the British Film Institute’s archives. Temple’s old partner in crime, Malcolm McLaren, in a 1991 interview, talks about “the London Mob” as a critical presence in the city’s history, one aspect of a continuous cycle of creation, destruction and rebirth that defines London.

A very specific sense of time and place has always been crucial to Julien Temple’s films. It could be that period on the brink of the 1960s, before The Beatles and the Stones, in Absolute Beginners; or the mid-Seventies of The Filth And The Fury – “peeling, crumbling, falling apart” – or perhaps even Canvey Island in the Fifties and Glastonbury in the 1980s. But for London – The Modern Babylon, Temple has a more ambitious reach: his plan is to cover not just one specific time period, but an entire century, give or take, of London life, beginning with the earliest filmed footage of the capital and running up to the present day.

The one through-line is Hetty Bower, a sprightly 106 year-old Hackney resident who remembers when going to watch Tower Bridge opening and closing “was an outing”. Nearly nine when World War I broke out, she recalls cheering soldiers “at Dalston Junction, going off in uniform, and we waved. And then I didn’t like what I saw when they started coming back.” A veteran of the 1936 Battle of Cable Street – “Mosley and his followers did not pass” – of today’s Occupy movement, she notes, “They’re asking for the basis of our society to be questioned, and I think that is correct.” Temple’s other interviewees range from Tony Benn to Ray Davies and Michael Horovitz (seen here both in footage from the International Poetry Incarnation at the Albert Hall in 1965 and in the present day), along side everyday Londoners, whose stories and memories provide a satisfyingly intimate element to the film’s powerful narrative sweep.

Temple’s piece is essentially a document of social transformation. From the British Empire at its peak, with Queen Victoria “opening her doors” to Jewish immigrants in the early 1900s, through Windrush up to the Eastern European influx of today, it’s part of what Suggs describes as “a process. People get taken in and become part of the city itself and change the city. And that’s the whole point. The place keeps changing.”

Some things, however, remain sadly the same. Tony Benn tells how “when I was very young, we were taught at school there were only two kinds of people in the world: the British and foreigners. And there were an awful lot of foreigners.” A Jamaican interviewee remembers how his 11-Plus exam “was given to another [white] guy. I found out later from other black guys I know that the same things happened to them.” In archive film, one white resident of Southall, home to a large South Asian community, says, “There’s nothing left in this town any more for English people.” One man, in footage from the 1970s, talks in chillingly reasonable tones about “the National Socialist way.”

But it’s not just immigrants who are repeatedly subjected to prejudice. Another thread in Temple’s film are the privations experienced by the working classes through the century, from the Victorian era to the property boom in the 1960s and again in the Eighties, as the docks were run down and eventually the land sold off to developers. “People feel that they’re being excluded from what many of us regard as our river,” says one East Ender, standing outside the entrance to a Thames-side gated community. One prescient scene from The Long Good Friday imagines a UK Olympic bid for the derelict Docklands area.

Tracing London’s history chronologically through exhaustively researched newsreel footage, contemporary interviews, songs and movies, Temple’s film is an impressive contribution to the already considerable body of work dedicated to mapping London. As you’d expect, this being Temple it’s not some dry academic work. Temple himself presides over the film as it unspools on multiple TV screens in a CCTV control centre. Black and white footage of horseguards riding through an Edwardian smog is cut to Underworld’s “Born Slippy”; scenes from Tony Hancock’s The Rebel are elided with film of – God! – Quentin Crisp posing for a life-drawing class in his underpants. The material from the Sixties – “the rebellion of the longhairs”, Pink Floyd at the UFO, the Grosvenor Square anti-war march, Twiggy, Terrence Stamp, the Stones in their pomp – is familiar but exhilaratingly cut by Temple, reminding me of the breathless editing of Beatles’ footage in Martin Scorsese’s George Harrison documentary.

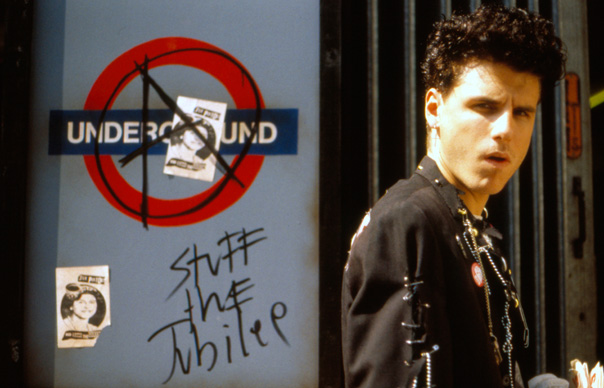

Temple sees London as a palimpsest, with layers of collective memory built up over time: images of a hippie girl in the 1960s handing out flowers to bemused commuters at Bond Street tube station are cut into film of a Victorian East End flower girl; film of protesting suffragettes is cut to X-Ray Specs’ “Oh Bondage! Up Yours”. 1920s debutantes, hippies, punks, New Romantics have all had their moment of glory in London’s history. “The good old days?” Says Suggs towards the end of Temple’s film. “There were no good old days. London doesn’t belong to anyone. It’s whoever’s on the go at any given moment.

London – The Modern Babylon will be released in the UK on August 3