Born Jean-Pierre Grumbach, the great French director renamed himself after *Moby Dick*’s author, and made films that paid homage to America’s hardboiled tradition, while practising a deeply French existentialism. The crime movies for which he’s best known are stripped to the bone, but crawl with strange, even surreal undercurrents. Although closely modelled on classic Hollywood gangster movies, they claimed the term "noir" back for France. This six-disc set contains four of his best thrillers, and two even more extraordinary films that help show where they came from. *Bob Le Flambeur* (1955) was his first crime movie, a moodily atmospheric, but unexpectedly wistful film. Shot in a twilight Paris, it’s the story of an aging gambler, a man out of time, assembling an impossible casino heist. Laying down Melville’s abiding theme - honour– it remains modern and truly surprising, as does *Le Doulos* (1962), with Jean Paul Belmondo pure punk as the rumoured stoolpigeon of the title. The plot is a confusion of double-crossing and revenge, Melville’s world a hazardous shadow-city of blank streets, isolated houses, cheap hotels. The free, tense energy and hard, easy humour makes clear why he was one of the few older homegrown directors France’s New Wave adored. His penultimate film, *Le Cercle Rouge* (1970) is an unqualified masterpiece, the crime-movie's *Once Upon a Time in the West*, the rituals of the heist refined to their essence. Alain Delon plays a glacial ex-con, planning to take down an exclusive Parisian jewellery store, even though he knows the cops are closing in. A steely, moody thing, with some the genre’s tensest set pieces and its own deeply mysterious vibe, it leads to Melville’s last movie, *Un Flic* (1972), with Delon reincarnated on the other side of the eternal cycle, the cop chasing the master thief this time. Melville’s fascination with a hidden underworld society can be explained by the fact that, during the early 1940s, he was a member of the French Resistance. The two other films here return to that period. *Leon Morin, Pretre* (1961), is unclassifiable. It begins by examining life for a woman left alone in an occupied town as the Nazis arrive, then shoots into casual metaphysics through her relationship with a raffish, radical young priest (Belmondo, at his most magnetic). Finally, *Army of Shadows* (1969), is another masterpiece, Melville’s most personal movie, and most devastating: an unblinking account of a Resistance unit who put aside all human feeling to devote themselves terribly to their cause, no matter how hopeless it seems. Melville applies the rhythms of his gangster movies, rendering the film as enthralling as it is upsetting: you can’t take your eyes away, but you don’t want to look - because, in this life or death struggle, the lives and the deaths actually mean something. EXTRAS: 3*Interviews with Melville associates, commentaries by French film historian Ginette Vincendeau. DAMIEN LOVE

Born Jean-Pierre Grumbach, the great French director renamed himself after *Moby Dick*’s author, and made films that paid homage to America’s hardboiled tradition, while practising a deeply French existentialism. The crime movies for which he’s best known are stripped to the bone, but crawl with strange, even surreal undercurrents. Although closely modelled on classic Hollywood gangster movies, they claimed the term “noir” back for France.

This six-disc set contains four of his best thrillers, and two even more extraordinary films that help show where they came from. *Bob Le Flambeur* (1955) was his first crime movie, a moodily atmospheric, but unexpectedly wistful film. Shot in a twilight Paris, it’s the story of an aging gambler, a man out of time, assembling an impossible casino heist. Laying down Melville’s abiding theme – honour– it remains modern and truly surprising, as does *Le Doulos* (1962), with Jean Paul Belmondo pure punk as the rumoured stoolpigeon of the title. The plot is a confusion of double-crossing and revenge, Melville’s world a hazardous shadow-city of blank streets, isolated houses, cheap hotels. The free, tense energy and hard, easy humour makes clear why he was one of the few older homegrown directors France’s New Wave adored.

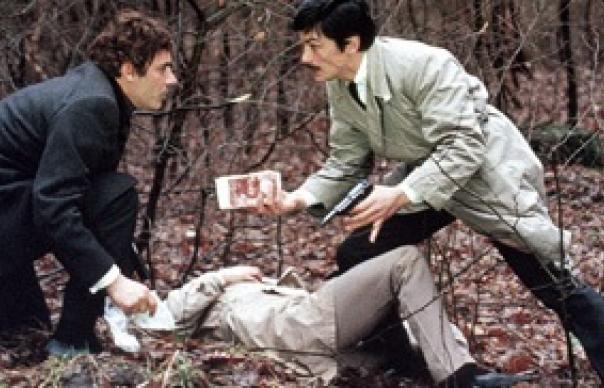

His penultimate film, *Le Cercle Rouge* (1970) is an unqualified masterpiece, the crime-movie’s *Once Upon a Time in the West*, the rituals of the heist refined to their essence. Alain Delon plays a glacial ex-con, planning to take down an exclusive Parisian jewellery store, even though he knows the cops are closing in. A steely, moody thing, with some the genre’s tensest set pieces and its own deeply mysterious vibe, it leads to Melville’s last movie, *Un Flic* (1972), with Delon reincarnated on the other side of the eternal cycle, the cop chasing the master thief this time.

Melville’s fascination with a hidden underworld society can be explained by the fact that, during the early 1940s, he was a member of the French Resistance. The two other films here return to that period. *Leon Morin, Pretre* (1961), is unclassifiable. It begins by examining life for a woman left alone in an occupied town as the Nazis arrive, then shoots into casual metaphysics through her relationship with a raffish, radical young priest (Belmondo, at his most magnetic).

Finally, *Army of Shadows* (1969), is another masterpiece, Melville’s most personal movie, and most devastating: an unblinking account of a Resistance unit who put aside all human feeling to devote themselves terribly to their cause, no matter how hopeless it seems. Melville applies the rhythms of his gangster movies, rendering the film as enthralling as it is upsetting: you can’t take your eyes away, but you don’t want to look – because, in this life or death struggle, the lives and the deaths actually mean something.

EXTRAS: 3*Interviews with Melville associates, commentaries by French film historian Ginette Vincendeau.

DAMIEN LOVE