Ferry aid: Roxy covers and much more from eternal Soft Boy... “What’s supposed to happen is you get slower and less vivid,” Robyn Hitchcock tells Uncut, matter-of-factly measuring out the career path that awaits all 60-something songwriters. “You get deeper and a bit more boring. Your colours dim and I assume that’s what happening to me.” At 61, Hitchcock’s musical palette is fading, the Hapshash and the Coloured Coat hues of the Soft Boys and the acid brights of his REM-sponsored 80s and 90s pomp giving way to a pleasing silvered tone of late. However, if his 20th solo album, The Man Upstairs, is less excitable than the likes of Underwater Moonlight, Fegmania! and Queen Elvis, it’s a change that many Hitchcock agnostics will welcome. A largely acoustic confection of sombre originals and tastefully-selected covers, The Man Upstairs was ushered into the world by Joe Boyd, the producer who coaxed landmark works from such Hitchcock idols as the Pink Floyd, the Incredible String Band and Nick Drake in their 1960s heyday. Infinitely more Pink Moon than “Arnold Layne”, it is as stark and forbidding a work in its way as 1990’s two-bob Blood On The Tracks, Eye, albeit studiously stripped of Hitchcock’s usual flashes of Spaniard In The Works surrealism and references to seafood. A gloriously demystified version of the Doors’ “The Crystal Ship” is among its highlights, but while Hitchcock continues to see himself as an ambassador from the lost Atlantis of 1960s pop, his spirit guide here is not the leather-trousered Jim Morrison, but the elegantly tailored Bryan Ferry. That reverence is most explicit on Hitchcock’s eviscerated reading of Roxy Music’s “To Turn You On”, which rehydrates the dessicated, studio-tanned original, from 1982’s ne-plus produced Avalon, the singer’s breathless urgency and eagerness to please a captivating counterpoint to Ferry’s weary chaleur. If the gangling Hitchcock could never hope to emulate Ferry’s louche detatchment, he manages to assimilate some of his pensive poise and lovelorn pessimism elsewhere. Romance is transformed into a tense stake-out on the perfectly-chiselled “San Francisco Patrol”, his recurring motif “can’t take my eyes off you” very much the twice-shyness of the once-bitten. Hitchcock’s appraisals of the Psychedelic Furs’ “The Ghost In You” and Norwegian indie-poppers I Was A King’s “Ferries”, are further proof of his unheralded – and entirely Ferryesque - ability to spirit his way inside a song, while the ghost of Bert Jansch walks on “Trouble In Your Blood”. Second person pronouns notwithstanding, it feels very much like a self-portrait of an artist whose work – even at its most exuberant – has always hinted at something naggingly unresolved underneath. “You’ve got a well-constructed shell,” Hitchcock rumbles. “Deep inside, you’re deep in hell.” If a Jerry Hall ever broke Hitchcock’s heart, then he has been discreet enough never to name and shame them, but – as it does on his favourite late-period Roxy Music albums - some spectral, lingering, emotional thundercloud hangs over The Man Upstairs. Painfully slow, and daubed with a harpy warble backing vocal from Anne Lise Frøkedal, closer “Recalling The Truth” harks back to that infinitely distant yet eternally resonant emotional big bang - “a window of bliss, that opens just once for the price of a kiss”. That window may have been slammed in Hitchcock’s face forever ago, but as much as it pines for lost and irretrievable things, The Man Upstairs is another faltering step closer to self-realisation from the man once introduced witheringly in his days as a folk club wannabe as “Cambridge’s answer to music”. “You hide from yourself but you’re tracking you down,” Hitchcock intones with a certain grim certainty on “Recalling The Truth”. The chase is getting slower maybe, with the light fading around him, but those autumn tones may have been what suited him best all along. Jim Wirth Q&A Robyn Hitchcock What was the appeal of making an album with Joe Boyd? Basically it’s the teenage Robyn getting the chance to do what he would have loved to think he was going to do in the future. The idea mixing originals and covers was totally Joe. He said: ‘Why don’t you make a record like Judy Collins did?’ And I thought: ‘Brilliant – let’s do Introducing Robyn Hitchcock - he’s this promising newcomer. He writes a few of his own songs but he knows the classics - here we go with this one from Bryan Ferry.’ You obviously adore Bryan Ferry. I am the opposite of him in so many ways. I feel like a shadow of Bryan Ferry. I have almost unconditional love for Bryan Ferry. I met him once. I poured a cup of tea for him in a hotel in Norway after a festival. Instantly, he is a man you want to genuflect to and pour out a cup of tea for. He said thank you my boy and tipped me a florin. I’ve still got it framed on my wall. Your work has got a lot less cluttered. Is that a conscious thing? I’ve just been chiselled away by life. The acid rain of existence etches you away. My earlier songs were a reaction to the shock of existence; I just couldn’t accept that I was. I’d just look around at my fellow creatures and think: ‘Fuck, this is not working.’ When you’re young and you have your life ahead of you, you can hang your head deep in mourning and look with loathing at the foibles of humanity, but after a certain age you’ve just got to get up and boogie. INTERVIEW BY JIM WIRTH

Ferry aid: Roxy covers and much more from eternal Soft Boy…

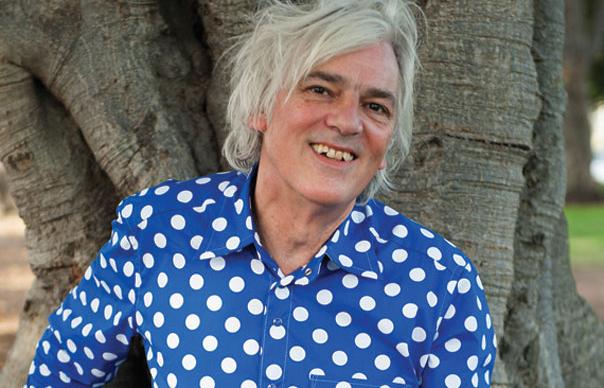

“What’s supposed to happen is you get slower and less vivid,” Robyn Hitchcock tells Uncut, matter-of-factly measuring out the career path that awaits all 60-something songwriters. “You get deeper and a bit more boring. Your colours dim and I assume that’s what happening to me.”

At 61, Hitchcock’s musical palette is fading, the Hapshash and the Coloured Coat hues of the Soft Boys and the acid brights of his REM-sponsored 80s and 90s pomp giving way to a pleasing silvered tone of late. However, if his 20th solo album, The Man Upstairs, is less excitable than the likes of Underwater Moonlight, Fegmania! and Queen Elvis, it’s a change that many Hitchcock agnostics will welcome.

A largely acoustic confection of sombre originals and tastefully-selected covers, The Man Upstairs was ushered into the world by Joe Boyd, the producer who coaxed landmark works from such Hitchcock idols as the Pink Floyd, the Incredible String Band and Nick Drake in their 1960s heyday. Infinitely more Pink Moon than “Arnold Layne”, it is as stark and forbidding a work in its way as 1990’s two-bob Blood On The Tracks, Eye, albeit studiously stripped of Hitchcock’s usual flashes of Spaniard In The Works surrealism and references to seafood.

A gloriously demystified version of the Doors’ “The Crystal Ship” is among its highlights, but while Hitchcock continues to see himself as an ambassador from the lost Atlantis of 1960s pop, his spirit guide here is not the leather-trousered Jim Morrison, but the elegantly tailored Bryan Ferry.

That reverence is most explicit on Hitchcock’s eviscerated reading of Roxy Music’s “To Turn You On”, which rehydrates the dessicated, studio-tanned original, from 1982’s ne-plus produced Avalon, the singer’s breathless urgency and eagerness to please a captivating counterpoint to Ferry’s weary chaleur.

If the gangling Hitchcock could never hope to emulate Ferry’s louche detatchment, he manages to assimilate some of his pensive poise and lovelorn pessimism elsewhere. Romance is transformed into a tense stake-out on the perfectly-chiselled “San Francisco Patrol”, his recurring motif “can’t take my eyes off you” very much the twice-shyness of the once-bitten.

Hitchcock’s appraisals of the Psychedelic Furs’ “The Ghost In You” and Norwegian indie-poppers I Was A King’s “Ferries”, are further proof of his unheralded – and entirely Ferryesque – ability to spirit his way inside a song, while the ghost of Bert Jansch walks on “Trouble In Your Blood”. Second person pronouns notwithstanding, it feels very much like a self-portrait of an artist whose work – even at its most exuberant – has always hinted at something naggingly unresolved underneath. “You’ve got a well-constructed shell,” Hitchcock rumbles. “Deep inside, you’re deep in hell.”

If a Jerry Hall ever broke Hitchcock’s heart, then he has been discreet enough never to name and shame them, but – as it does on his favourite late-period Roxy Music albums – some spectral, lingering, emotional thundercloud hangs over The Man Upstairs. Painfully slow, and daubed with a harpy warble backing vocal from Anne Lise Frøkedal, closer “Recalling The Truth” harks back to that infinitely distant yet eternally resonant emotional big bang – “a window of bliss, that opens just once for the price of a kiss”.

That window may have been slammed in Hitchcock’s face forever ago, but as much as it pines for lost and irretrievable things, The Man Upstairs is another faltering step closer to self-realisation from the man once introduced witheringly in his days as a folk club wannabe as “Cambridge’s answer to music”.

“You hide from yourself but you’re tracking you down,” Hitchcock intones with a certain grim certainty on “Recalling The Truth”. The chase is getting slower maybe, with the light fading around him, but those autumn tones may have been what suited him best all along.

Jim Wirth

Q&A

Robyn Hitchcock

What was the appeal of making an album with Joe Boyd?

Basically it’s the teenage Robyn getting the chance to do what he would have loved to think he was going to do in the future. The idea mixing originals and covers was totally Joe. He said: ‘Why don’t you make a record like Judy Collins did?’ And I thought: ‘Brilliant – let’s do Introducing Robyn Hitchcock – he’s this promising newcomer. He writes a few of his own songs but he knows the classics – here we go with this one from Bryan Ferry.’

You obviously adore Bryan Ferry.

I am the opposite of him in so many ways. I feel like a shadow of Bryan Ferry. I have almost unconditional love for Bryan Ferry. I met him once. I poured a cup of tea for him in a hotel in Norway after a festival. Instantly, he is a man you want to genuflect to and pour out a cup of tea for. He said thank you my boy and tipped me a florin. I’ve still got it framed on my wall.

Your work has got a lot less cluttered. Is that a conscious thing?

I’ve just been chiselled away by life. The acid rain of existence etches you away. My earlier songs were a reaction to the shock of existence; I just couldn’t accept that I was. I’d just look around at my fellow creatures and think: ‘Fuck, this is not working.’ When you’re young and you have your life ahead of you, you can hang your head deep in mourning and look with loathing at the foibles of humanity, but after a certain age you’ve just got to get up and boogie.

INTERVIEW BY JIM WIRTH