Ken Russell's controversial classic, restored to its original glory... “I guess I’ve been a voyeur all my life”, wrote Ken Russell in his 1989 autobiography, and he always assumed his audiences were the same – that voyeurism, in fact, defined cinema’s appeal. By the time he came to make The Devils – in which he found a subject matter that fully justified the hysterical pitch of his movie making – it was 1971, and he had just come off The Music Lovers, his pyrotechnic ode to Tchaikovsky, in which the composer’s obsessions with both work and his male lover cause his wife to seek male attentions elsewhere. The Devils would put Russell in similar straits: while he was consumed with work, his wife Shirley, the film’s costume designer, began an extramarital affair that ended in divorce. The Devils, Russell also conceded, was “The last nail in the coffin of my Catholic faith”. The story it tells is of a political conspiracy in the name of Christ. Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave), head of an enclosed Ursuline convent in the walled town of Loudun, begins having blasphemous fantasies about the popular local priest, Father Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), already known as a ladies’ man. Jeanne’s possession eventually spreads to the rest of the order, and before long the whole convent is seething with lewdness. Cardinal Richelieu, puppetmaster over the weak king Louis XIII, scents an opportunity to break down one of France’s last independent walled strongholds, part of an ongoing campaign to reduce the power of the feudal aristocracy. So he engineers an Inquisition, directing the nuns’ possession against Grandier. Russell plays up the tragedy by focusing on Grandier as a happy, romantic newlywed, wrenched from marital bliss, shaved, totured and delivered up to a kangaroo court. The conclusion is an epic immersion in the sensation of pain, as the camera tracks the bloodied, broken Grandier on his final, agonised journey towards the stake. The film was an adaptation of John Whiting’s play, itself a staging of Aldous Huxley’s The Devils Of Loudun, which novelised real events that took place in the 1630s. The film was butchered by the censors, especially in America (‘circumcised’, Russell called it) – the first cut included a dream sequence of Christ raped while hanging on the cross, and two quack exorcists (one played by a leering Brian Murphy, later of George And Mildred) analysing Jeanne’s syringed stomach contents for a blasphemous admixture of sperm and communion wafer. Hideous it might have been, but these were facts drawn (by Russell’s brother in law, a Medieval French lecturer at the Sorbonne) from the historical record. Plot aside, Russell contrived to make The Devils an orgy for the eyes and ears. Derek Jarman’s production design is exceptional by any standards: Loudun is a colossal walled city/amphitheatre in tiled white brick, more like a public convenience than a fortress (the sanitized interior is contrasted with the filth and plague-ridden bodies piling up outside). The sets provide an amphitheatre for the film’s many arresting images: Redgrave’s incredible study of wracked, twitching, frustrated lust; plague pits bursting with swaddled corpses; Richelieu’s monstrous, Borges-like scriptorium; Grandier’s residence ransacked before his eyes; Louis XIII (Graham Armitage) sportingly picking off peasants with a blunderbuss. During shooting, Russell installed a quadraphonic sound system around the set, getting his cast in the mood with blasts of Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel. But even that demonic opera was trumped by Peter Maxwell Davies’s original soundtrack, a discordant orchestral nightmare that exudes total religious dementia. It’s a marvellous use of dissonant music in cinema, and remains churning in the mind long after the closing credits. Rarely screened on television, and only released in its censored form on a Warner US DVD, The Devils has remained more talked about than seen for four decades. The BFI’s glorious restoration presents the original UK ‘X’ certificate version – the longest version so far available – breathing new life into its artful colour scheme and with a host of extra features and essays that illuminate Russell’s intentions beyond mere notoriety, including a commentary by the director himself. “Corruption and mass brainwashing by Church and State and commerce is still with us, as is the insatiable craving for sex and violence by the general public,” was his later justification for the film’s existence, and we need a purgative against those unholy forces now, more than ever. EXTRAS: Commentary, two documentaries, on-set footage, director Q&A, trailers, plus Russell’s 1958 short Amelia And The Angel. 7/10 Rob Young

Ken Russell’s controversial classic, restored to its original glory…

“I guess I’ve been a voyeur all my life”, wrote Ken Russell in his 1989 autobiography, and he always assumed his audiences were the same – that voyeurism, in fact, defined cinema’s appeal. By the time he came to make The Devils – in which he found a subject matter that fully justified the hysterical pitch of his movie making – it was 1971, and he had just come off The Music Lovers, his pyrotechnic ode to Tchaikovsky, in which the composer’s obsessions with both work and his male lover cause his wife to seek male attentions elsewhere. The Devils would put Russell in similar straits: while he was consumed with work, his wife Shirley, the film’s costume designer, began an extramarital affair that ended in divorce.

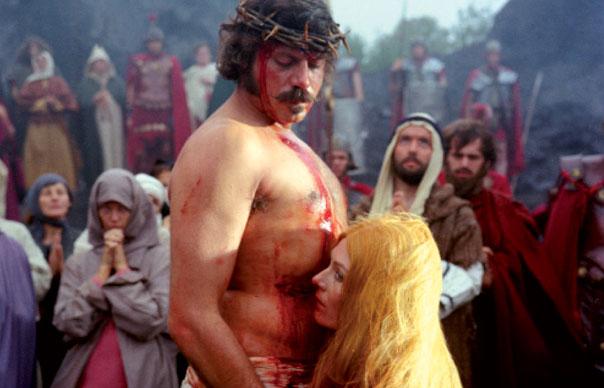

The Devils, Russell also conceded, was “The last nail in the coffin of my Catholic faith”. The story it tells is of a political conspiracy in the name of Christ. Sister Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave), head of an enclosed Ursuline convent in the walled town of Loudun, begins having blasphemous fantasies about the popular local priest, Father Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), already known as a ladies’ man. Jeanne’s possession eventually spreads to the rest of the order, and before long the whole convent is seething with lewdness. Cardinal Richelieu, puppetmaster over the weak king Louis XIII, scents an opportunity to break down one of France’s last independent walled strongholds, part of an ongoing campaign to reduce the power of the feudal aristocracy. So he engineers an Inquisition, directing the nuns’ possession against Grandier. Russell plays up the tragedy by focusing on Grandier as a happy, romantic newlywed, wrenched from marital bliss, shaved, totured and delivered up to a kangaroo court. The conclusion is an epic immersion in the sensation of pain, as the camera tracks the bloodied, broken Grandier on his final, agonised journey towards the stake.

The film was an adaptation of John Whiting’s play, itself a staging of Aldous Huxley’s The Devils Of Loudun, which novelised real events that took place in the 1630s. The film was butchered by the censors, especially in America (‘circumcised’, Russell called it) – the first cut included a dream sequence of Christ raped while hanging on the cross, and two quack exorcists (one played by a leering Brian Murphy, later of George And Mildred) analysing Jeanne’s syringed stomach contents for a blasphemous admixture of sperm and communion wafer. Hideous it might have been, but these were facts drawn (by Russell’s brother in law, a Medieval French lecturer at the Sorbonne) from the historical record.

Plot aside, Russell contrived to make The Devils an orgy for the eyes and ears. Derek Jarman’s production design is exceptional by any standards: Loudun is a colossal walled city/amphitheatre in tiled white brick, more like a public convenience than a fortress (the sanitized interior is contrasted with the filth and plague-ridden bodies piling up outside). The sets provide an amphitheatre for the film’s many arresting images: Redgrave’s incredible study of wracked, twitching, frustrated lust; plague pits bursting with swaddled corpses; Richelieu’s monstrous, Borges-like scriptorium; Grandier’s residence ransacked before his eyes; Louis XIII (Graham Armitage) sportingly picking off peasants with a blunderbuss.

During shooting, Russell installed a quadraphonic sound system around the set, getting his cast in the mood with blasts of Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel. But even that demonic opera was trumped by Peter Maxwell Davies’s original soundtrack, a discordant orchestral nightmare that exudes total religious dementia. It’s a marvellous use of dissonant music in cinema, and remains churning in the mind long after the closing credits.

Rarely screened on television, and only released in its censored form on a Warner US DVD, The Devils has remained more talked about than seen for four decades. The BFI’s glorious restoration presents the original UK ‘X’ certificate version – the longest version so far available – breathing new life into its artful colour scheme and with a host of extra features and essays that illuminate Russell’s intentions beyond mere notoriety, including a commentary by the director himself. “Corruption and mass brainwashing by Church and State and commerce is still with us, as is the insatiable craving for sex and violence by the general public,” was his later justification for the film’s existence, and we need a purgative against those unholy forces now, more than ever.

EXTRAS: Commentary, two documentaries, on-set footage, director Q&A, trailers, plus Russell’s 1958 short Amelia And The Angel.

7/10

Rob Young