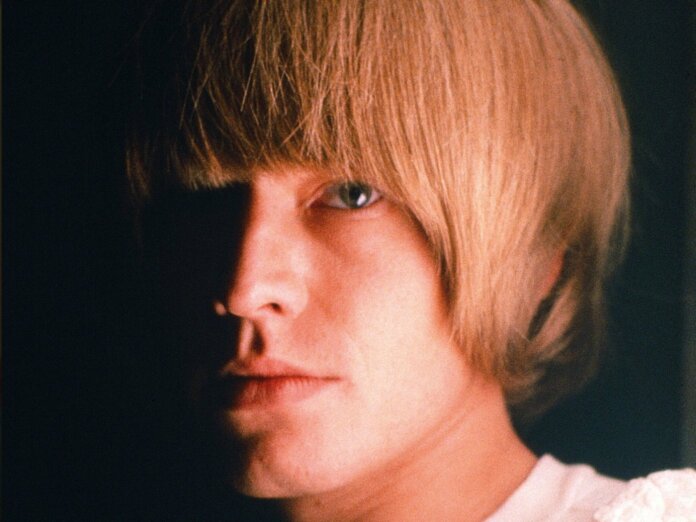

In 1963, Nick Broomfield spotted Brian Jones on a Cheltenham-bound train, and was invited into his first-class compartment to chat. “I was 14 and at boarding school,” the director recalls, “and he represented an anti-authoritarian way of being. It turned out he was a trainspotter, and was on that line quite a lot. He was extremely friendly, and happy for me to come in and sit down. It’s one of those events you remember.”

Broomfield’s new BBC documentary, The Stones And Brian Jones, contrasts that first, sweet encounter with Bill Wyman’s recollection of “a fucker… I don’t want to say evil, but he was really cruel.” “Stories don’t always have to be about saints,” Broomfield argues. “But Brian was talented, and I wanted to find out what had gone wrong.”

Wyman is the sole Stone to contribute to the doc, eagerly pulling out stems from his archive’s multi-tracks to isolate Jones’ crucial slide guitar on “Little Red Rooster”, and his recorder spiralling through “Ruby Tuesday”. “Bill felt that Brian was badly let down in terms of the Stones’ legacy,” Broomfield says, “and that his contribution needs to be recognised.” Jones’ lack of songwriting was his Achilles’ heel. But newly uncovered tapes find him tentatively seeking his own creativity, playing guitar with Hendrix, and writing a stumbling, baroque song with Ready Steady Go! presenter Michael Aldred. They suggest possibilities that Jones lacked the confidence and discipline to pursue.

A stash of letters discovered in 2019, meanwhile, show the painful generation gap between Jones and his parents, who threw him out aged 16. “There was a very hurt little boy there,” Broomfield says. He also interviews Jones’ surviving ex-girlfriends, five of whom were abandoned with a child, but offer surprisingly affectionate portraits. “All the women I spoke to said that when he was with you, he gave you everything, and they felt amazing with him. He represented a high point in their lives. They still seem to love him deeply.”

The film’s most touching revelations lie in the home movies of Brian as a boy. Amid footage of Stones gig riots, film of his teenage haunt Filby’s Jazz Club is just as thrilling in its way. “That was a liberation movement in uptight Cheltenham, and must have been absolutely wonderful for Brian. People were playing Howlin’ Wolf records, and the club was an adventure into the unknown, looking for a different kind of future, giving Brian and his friends an enormous lust for life.”

The film is in some ways a companion piece to Broomfield’s Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love, which showed the collateral human damage to Leonard Cohen’s liberated lifestyle in Hydra in the early ’60s. As Keith Richards says of Jones: “Not everyone makes it.”

“It’s hard to imagine the uncharted territory they were going through,” Broomfield reflects. “Just look at the concerts’ wonderful anarchy. I went to some, and there was the sense of freedom and a bright future ahead of you. It was that wondrous naïveté and optimism in which I met Brian on the train. Then just six years later it had changed.”

Broomfield focuses on footage of the young, innocent-looking fans at the Stones’ Hyde Park gig after Jones’ death on July 3, 1969. He was there himself. “We were in real shock that it had all ended so quickly. It just wasn’t supposed to be like that. Brian’s death made you pause and think, ‘What happened? How did somebody who was an embodiment of all our dreams come to this?’ Some part of the experiment was over.”