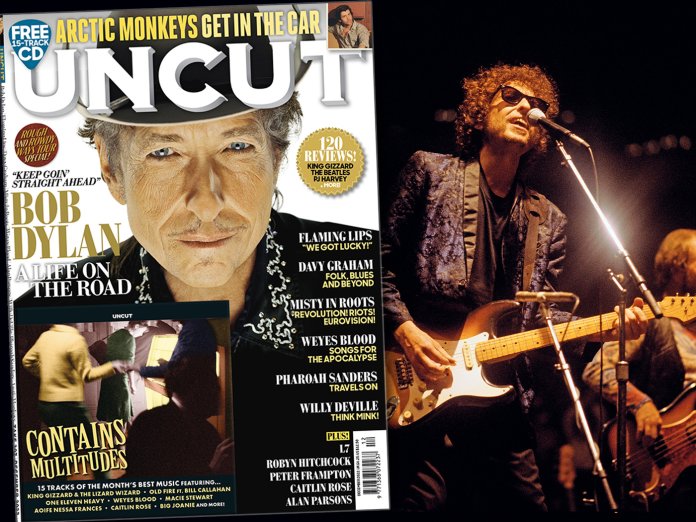

As BOB DYLAN live fever reaches its peak, Uncut travels to Stockholm to experience the Rough And Rowdy Ways Tour up close. First, though, Uncut’s writers – and some close associates – relive their own legendary encounters with Bob from his past seven decades of challenging, constantly evolving live music. Take your seat alongside us at Sheffield City Hall in 1965, Madison Square Garden in 1974, the Spokane Opera House in 1980 and beyond, down 50 transformative years, in our definitive, eye-witness report on Dylan in concert, in the latest issue of Uncut magazine – in UK shops from Thursday, October 13 and available to buy from our online store.

To give you a flavour of our latest cover story, Richard Williams’ recalls an early sighting of Dylan in the UK, still in his first incarnation as boho troubadour, at Sheffield City Hall on April 30, 1965…

A handful of folk-club appearances during a stay in London in December 1962 to record the BBC TV play Madhouse On Castle Street and a sold-out concert at the Royal Festival Hall in May 1964 were Bob Dylan’s only British appearances before he stepped on stage at Sheffield’s City Hall on the evening of April 30, 1965, opening a seven-date UK concert tour. None of us present that night knew was that this was our last chance to see a full-length exposition of Dylan in his first incarnation: the solo troubadour on stage with nothing more than an acoustic guitar and a bunch of harmonicas.

There was no support act. With no preliminaries, he launched straight into “The Times They Are A-Changin’”, probably his most famous song just then, since it had been released as a single in the UK in advance of the tour, making the Top 10. He sang it straight, neither leaning in to the song nor drawing back, playing it just a touch too fast, as if to get it out of the way. It was a first tiny indication that Dylan might be capable of ambivalent feelings towards his own work, or at least towards the way it was absorbed and used by his audience. A lot had changed since he chose to open another concert with the song in November 1963, two or three nights after JFK was killed and just a week after he’d recorded it in New York. Now you could tell he felt that the song had left his ownership; he was no longer responsible for it, nor would he allow himself to be defined by the simple slogan that had spoken to and for so many.

As it ended, the applause was ardent. In his documentary Don’t Look Back, DA Pennebaker captured how it faded to silence as Dylan stepped back, slid a capo on to the second fret and took his time choosing a harmonica from the selection on a bar stool next to his microphone stand. Although there were plenty of school-age fans present to see a performer who was now a pop star, albeit a new variant of the genre, the audience’s behaviour was that of the concert hall or the folk club, attentive and respectful.

“To Ramona” was warmer. Now he was inhabiting the song rather than just singing it. But with his third song came the first revelation. Bringing It All Back Home would not be released in the UK until the following month, so the deep, dark, extended complexity of “Gates Of Eden” came as a shock, redoubled a few minutes later by “It’s Alright Ma…”, its rapid-fire lyric precisely enunciated, its harmonica stabs shooting through the hall. Then “Love Minus Zero”, “Mr Tambourine Man” and “It’s Over Now, Baby Blue”, all new-minted. To hear these epic songs for the first time, sung with such commitment and control, was to be given a vision of new feelings, new possibilities. They were like starbursts against the backdrop of the already familiar songs: “Don’t Think Twice…”, “…Hattie Carroll”, “With God On Our Side” and others.

If our minds were reeling as we left the hall, his was already elsewhere. A month after returning home he was in a New York studio, recording 20 takes of “Like A Rolling Stone”. In July he was scandalising the Newport Folk Festival with a raucous band including Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper. And in May 1966 he would return to Britain with The Hawks, shredding the last of the old restraints.

PICK UP THE NEW ISSUE OF UNCUT TO READ THE FULL STORY