Iury Lech’s second album, Música Para El Fin De Los Cantos (‘Music For The End Of The Songs’), has taken a while to reach its audience. Originally released by Spanish label Hyades Arts, which was run by writer and director Antonio Diaz and musician Dr Héctor, its understated beauty eventually attracted a wave of bloggers who were interested in albums that slipped between genres, sitting as it does between minimalism, New Age and Fourth World musics. Reissued five years ago by CockTail d’Amore, with altered artwork, for this reissue, Wah Wah and Lech have gone back to the master tapes and restored the original cover.

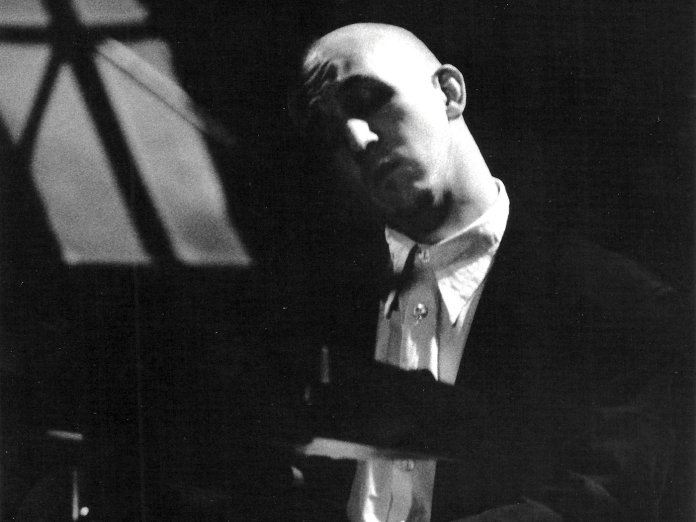

Lech, a multi-disciplinary creator of Ukrainian origin, recorded the album across 1989 and 1990, while he was based in Barcelona. Indeed, he’s spent most of his life in Spain, pursuing an unpredictable career that’s taken in music, film, literature and multimedia – his first album, 1989’s cassette-only Otra Rumorosa Superficie, drew from soundtracks to several of his early-’80s films. His music, rich with gentle, poetic synthesis and luxuriant, slow-moving melody, also sat particularly well within a broader scene in Spain that explored the nexus of post-industrial, post-minimalism, and nascent techno/electronica, and Música Para… nestles neatly alongside contemporaneous work from the likes of Esplendor Geometrico, Miguel A Ruiz, Adolfo Nuñez, Pep Llopis, José Luis Macias, Finis Africae, Orquesta De Las Nubes and Mecanica Popular.

“Cuando Rocío Dispara Sus Flechas” (“When Rocío Shoots Her Arrows”) opens Música Para… with dizzy arpeggio patterns, suggesting the Berlin School relocated to sunnier climes. But as with much of Música Para…, Lech soon takes this composition in other directions – languid yet piercing high-pitch tones repeatedly rupture the surface of “Cuando Rocío…”, lending it a tense beauty, as electric piano spirals and descends into the song’s silences. “Barreras” (“Barriers”) follows, a chime-scape of clacking, glistening textures, see-sawing a simple chord change over a whirring hum, its gentle grandeur suggesting the Cocteau Twins’ “Lazy Calm”, from their 1986 album Victorialand, if it had been arranged by Portuguese composer Nuno Canavarro.

If “De La Melancolia” (‘Of Melancholy’) plays out loosely like a variation on a theme – cellular melodies repeating over pulsing drones that hint at natural phenomena and shape-shifting, rhizomatic networks – “Ukraïna” (‘Ukraine’), the album’s centrepiece, is more personal, internalised, a 17-minute hymn to Lech’s family home that shimmers in pellucid light, a synthetic choir singing wordless, ghostly chants; it has a similar sense of ‘epic stasis’ as Popol Vuh’s “Vuh”, from In Den Gärten Pharaos, but this feels like the ecstatic afterglow. By the time we reach the astral analgesic of the closing “Postmeridiano” (‘Afternoon’), Música Para…’s sanctified ambience has done its work: time has slowed to a crawl, but blissfully so.