During 1973, the Rainbow – a palatial former cinema in London’s Finsbury Park – was arguably the home of rock in Britain. In October, you could take in a Lou Reed residency, with the New Yorker resplendent in his Rock’n’Roll Animal phase. The following month, Pink Floyd, fresh from the success of The Dark Side Of The Moon, played a tribute concert for the recently injured Robert Wyatt. A week later, Roxy Music’s Stranded tour reached the capital, introducing dazzled audiences to a post-Eno future. Just a few days after, on November 19, Miles Davis returned to the Rainbow for the third and final time that year. Ostensibly a jazz trumpeter, Davis was now as flamboyant as Roxy, as cutting and charismatic as Reed and as exploratory as the Floyd.

“He travelled the world like a rock star,” says Colin Hodgkinson, whose band Back Door had supported Davis at the Rainbow during an earlier appearance on July 10 that year. “The Rainbow was a proper rock venue, a great venue with good sound. He had the big sunglasses and all that – and a red trumpet, I think. Oh yeah, that was very unusual.”

Davis had been at the forefront of jazz for decades; now nearing 50, he was once again in the middle of something new. “There was some great, great shit,” recalls Dave Liebman, on saxophone that night in July. “When he picked up the trumpet to play, the focus was incredible. It was like a laser beam from another planet.”

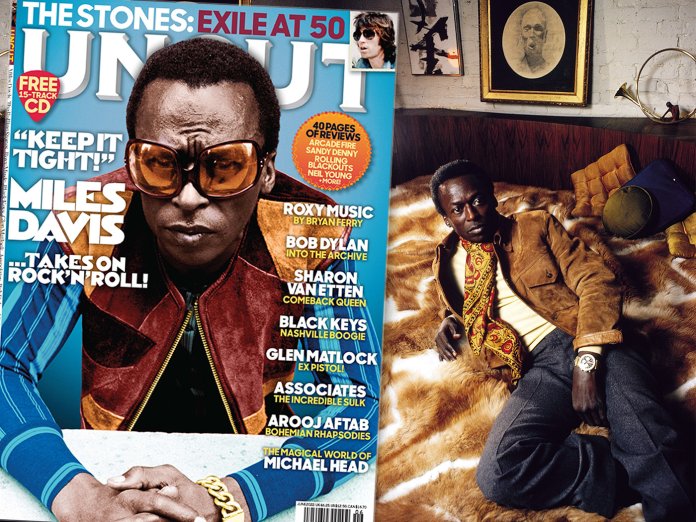

When Davis had first appeared at the Rainbow on October 1, 1960, during his debut British tour, he was basking in the glow of the previous year’s Kind Of Blue, leading a now-legendary band – including Jimmy Cobb and Paul Chambers – finely turned out in immaculate Italian suits. But in 1973, Davis was the ringmaster of a psychedelic funk troupe – as heavy, amplified and out-there as the most riotous rock group. The suits were gone, replaced by tasselled leather jackets, flares, high-heeled boots, sequinned vests, scarves and huge, insectoid sunglasses.

“People thought Miles was turning his back to the audience,” says Davis’s bassist, Michael Henderson. “But that was so he could watch his own band – so he could stare through those glasses at us. Being in that band, it was like you were with some bizarre basketball team. Music can be anything. We didn’t rehearse… we’d have some heads [melody lines] we would play, and we’d improvise the rest of it. It was a well-oiled machine. Miles enjoyed it.”