The first ever review of Tinariwen in the UK media came 21 years ago in the March 2001 issue of Uncut, when this intrepid critic travelled to see them play at “the world’s remotest music festival” in the southern Sahara in Mali. It was not a journey for the faint-hearted, involving a six-hour flight from Paris to Gao on the River Niger, followed by a long day’s 4×4 drive across the desert to Kidal, Tinariwen’s base. From there it was a further day’s drive deep into the Adrar des Ifoghas, an isolated region of rocks and more sand, nestling the borders with Algeria and Niger, and regarded by the Tuaregs as part of their ancestral nomadic lands.

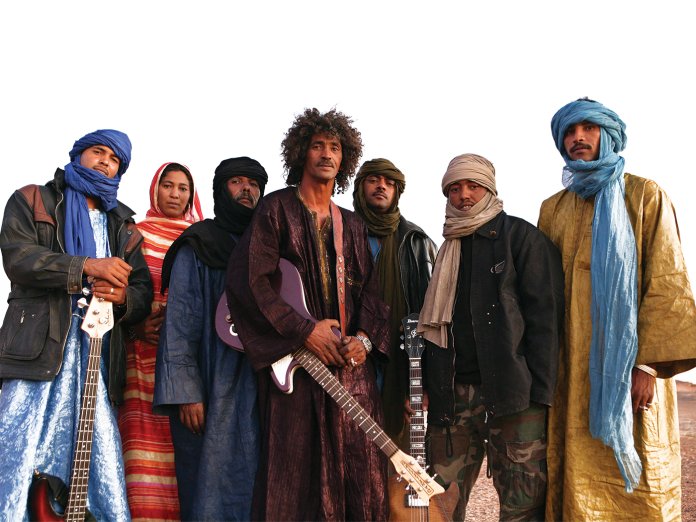

It was a hard and unforgiving site for a festival, baking hot by day and freezing by night, yet not without a stark exhilarating beauty. There, to a crowd of sword-wielding Tuareg warriors on camels and a handful of curious Westerners, Tinariwen played under a total eclipse of the moon, delivering what Uncut described as a “raw and earthy” set of “gutsy rebel songs” fronted by “four fearsome-looking turbaned Tuaregs all playing brilliant electric guitar”.

Since then, Tinariwen’s “desert blues” has become a familiar fixture. The band has toured the globe, collaborated with a host of Western rock stars and in 2010 won an Uncut Music Award for their fourth album Imidiwan: Companions. So two decades later it’s instructive to go back to the group’s debut and recall just how strange and mysterious, hypnotic and exotic Tinariwen sounded on first encounter.

Produced by Justin Adams at the same time as their appearance at the first Festival In The Desert, The Radio Tisdas Sessions was recorded at a Tamashek-language radio station in the desert outpost of Kidal, where the electricity supply only worked between 7pm and midnight, powered by solar panels but prone to regular breakdowns and failure.

Yet from drought and poverty to civil war and exile, coping with adversity is what Tuareg people have always done, and Tinariwen emerged with a resilient debut that captured the raw and unmediated sound of their live set and, indeed, includes a live track from that festival performance under the stars as one of its highlights.

Although the sound is earthily authentic, it’s also softer than the later Tinariwen style, when the guitars were cranked up and the rhythm section given additional heft, not least to meet the demands of playing to rock audiences at Glastonbury and Coachella. Indeed, tracks such as “Le Chant Des Fauves” and “Nar Djenetbouba”, both sung by Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, with their gently loping, camel-gait rhythms and fluid, crystalline guitar lines, might reasonably be termed “desert folk-rock”.

The Radio Tisdas Sessions is the only Tinariwen album to feature Kedou Ag Ossad, whose four tracks dig deepest and most fiercely into the blues, pointing the way to the group’s later, heavier sound and befitting his status as a legendary Tuareg insurgent who once attacked and captured a Malian army gun-post armed only with dagger and sword.

By the time of Tinariwen’s second album, 2004’s Amassakoul, three of the six guitarists on The Radio Tisdas Sessions had gone, leaving Ibrahim, Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni and Touhami Ag Alhassane as the core songwriters, all of whom remain mainstays of the group to this day. International touring had begun to broaden their horizons, while Robert Plant (who received a “thank you” in the album’s credits) had made the journey in the opposite direction and performed alongside them at the 2003 edition of the Festival In The Desert.

Recorded in a fully equipped studio in the Malian capital of Bamako, songs such as “Oualahila Ar Tesninan” have a more eclectic but still authentic aesthetic and a tougher edge, by far the group’s hardest rocking track by this point, and “Chatma”, with its militant, independence-demanding lyric and call for international support. Elsewhere, “Assoul” is a stripped-down choral chant accompanied only by wooden flute and didgeridoo, and “Ténéré Daféo Nikchan” is a vehicle for Ibrahim’s solo voice and guitar, sounding as deep and mysterious as any 1930s field recording from the Mississippi Delta.

Tinariwen would go on to make more accomplished albums featuring rocked-up collaborations with Kurt Vile and Mark Lanegan and members of TV On The Radio, Wilco and Red Hot Chilli Peppers, among others. But there’s a thrill in hearing them again pure and unadulterated, before they burst out of the desert to change the face of world music. Two decades on, familiarity with Tinariwen’s unique groove has not dimmed its allure.