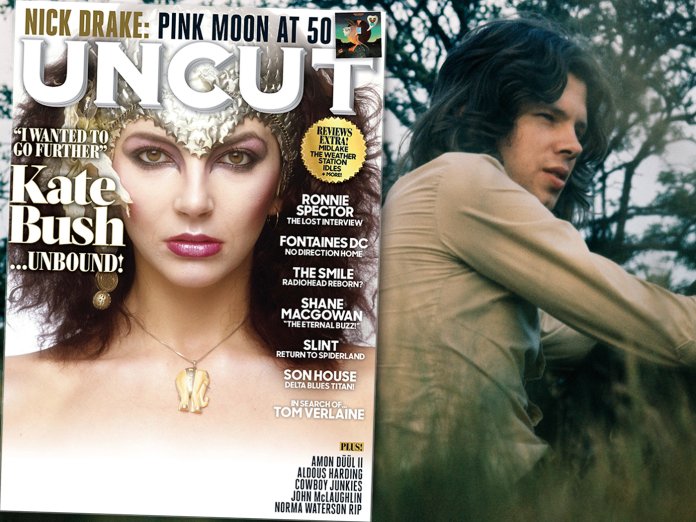

During the small hours of October 30, 1971, and again the following night, Nick Drake entered Sound Techniques studio in Chelsea to record his third, and final, album. Pink Moon was a quiet revolt. While Drake’s first two albums, Five Leaves Left (1969) and Bryter Layter (1971), were lush, orchestrated, beautifully arranged, Pink Moon was stripped bare. The only person present other than Drake during the sessions was Sound Techniques owner and engineer John Wood. Save for a brief, simple piano overdub on the title track, the album featured just Drake’s voice and guitar. The 11 songs spanned a mere 28 minutes. To describe Pink Moon as stark is to undersell its radical minimalism.

“Five Leaves Left was very easy,” recalls Joe Boyd, who signed Drake to his Witchseason roster in 1968 and produced the first two records. “Bryter Layter was more rushed and Nick and I clashed over his vision. He had this idea that each side would start and end with an instrumental. I felt it was a bit MOR. The moment Bryter Layter was done, Nick turned to me and said, ‘I’m going to do my next album with just guitar and voice.’ I took it as a rebuke.”

In the 50 years since its release on February 25, 1972, Pink Moon has slowly become one of the most mythologised records of the 20th century. It has become synonymous with Drake’s decline and death, on November 25, 1974, aged 26, from an overdose of antidepressants. It is hard to unravel its sadness from the sadness of his life – yet the album is also luminous, uncannily beautiful, limitless in its scale and scope.

Though commercially unsuccessful at the time, Pink Moon wasn’t released into a void. Island Records pushed the LP with full-page ads in the music weeklies and it was widely reviewed. There was a sense, however, that critics had tired of Drake’s reticence. His reluctance to play live was already notorious, and the unvarnished sound of the record seemed a further act of wilful self-sabotage. “Maybe it’s time Mr Drake stopped acting so mysteriously and started getting something properly organised for himself,” snapped

Jerry Gilbert, previously a champion of Drake, in Sounds.