Ideas forever above their station, baroque two-piece Nirvana were thrown to the wolves somewhat in 1967 when they were billed to play an Island Records showcase at London’s Saville Theatre. With the stage still half set for a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (featuring Cleo Laine and Bernard Breslaw), and the audience eagerly awaiting new rock sensations Traffic, Patrick Campbell-Lyons, Alex Spyropoulos and their mini-orchestra were barely audible. “We had only had three rehearsals,” Campbell-Lyons recalls ruefully in the sleevenotes to this remastered vinyl collection of their five studio LPs, plus an unreleased sixth. “It was a dreadful experience.”

Wobbly-voiced aesthetes with no stomach for paying their musical dues, the original Nirvana found themselves on the wrong side of history as rock got heavy in the late 1960s, but still had a magical career. They made the first rock opera, got doused in paint by Salvador Dalí live on French TV, and even if their most celebrated song (the phasers-set-to-stun “Rainbow Chaser”) was never a huge hit, Songlife is a suitably gigantic testament to a band that – like the Odessey And Oracle-era Zombies or Big Star – failed on the very grandest of scales.

Penny Valentine clocked something of Nirvana’s weedy, proto-indie-pop vibe when she reviewed their Sacha Di-stellar 1967 debut single, “Tiny Goddess”, for Disc, noting that Campbell-Lyons had “a funny little voice of incredible sadness”. Born in Waterford, Campbell-Lyons moved to London in the early 1960s, playing with R&B bands in Ealing before his quirky songs earned him a first bash at the big time with Hat And Tie, a duo with future Roxy Music, Sex Pistols and Pulp producer Chris Thomas.

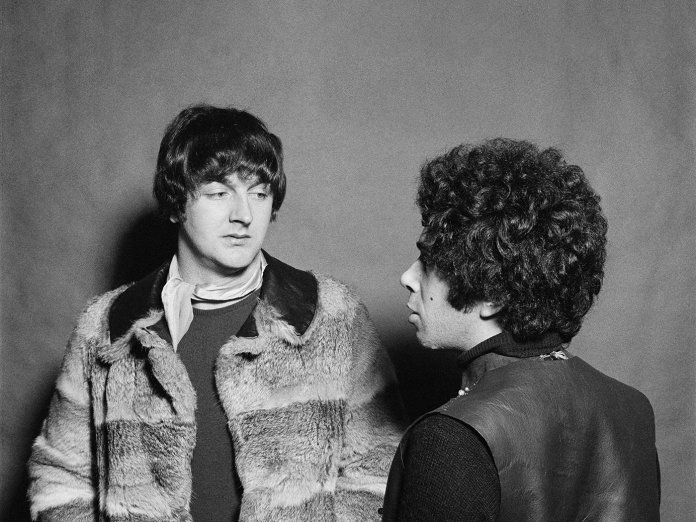

However, a greater adventure began when he was introduced to Spyropoulos at La Gioconda coffee house on Denmark Street. The Greek cinephile had abandoned his legal studies in Paris to try his luck in peak-groovy England, and after sketching out some widescreen tunes with Campbell-Lyons at Spyropoulos’s west London flat, the pair became one of Island’s first non-reggae signings. Label boss Chris Blackwell saw the potential in their home demos, and – perhaps rashly – encouraged them to bring in an orchestral arranger, and to think big.

Their debut album, The Story Of Simon Simopath, emerged just before Christmas 1967. A head-shop fairytale, it charts the adventures of a depressed youngster who finds happiness on the far side of the cosmos after becoming a space pilot, its monstrous tweeness mitigated by brilliant, primary-coloured songs: “Satellite Jockey”, “Wings Of Love” (as covered by Herman’s Hermits) and the happy-clappy “We Can Help You” (an almost hit for The Alan Bown!). Meanwhile, lush centrepiece “Pentecost Hotel” promises a refuge for “people with a passport of insanity”, a moving exemplar of how Nirvana hinted at emotional fragility behind their crushed-velvet wall of sound.

Simon Simopath proved a hard sell in what was still a singles-oriented age, and Nirvana foregrounded their rococo pop sensibility for 1968’s All Of Us. Their musical calling card, “Rainbow Chaser” has ELO-style strings, wild stereo phasing and slyly transgressive lyrics (“I can talk to him, and I can love him”), but stalled at No 34 in the UK charts in May 1968. It’s a stunning, impish period piece, but the rapturous “The Touchables (All Of Us)” might be even more perfectly crafted, though it was perhaps not a natural fit as the title song for the film of the same name: a sexy pop drama based on an idea by Performance writer Donald Cammell. More modest thrills lurk elsewhere, not least the cheeky use of the word “wanky” on “Frankie The Great”, and Spyropoulous’s psychedelic Astrud Gilberto impersonation, “You Can Try It”.

Unfazed by public indifference, Nirvana doubled down on the pomp for their third LP, but Island politely declined to release it, Blackwell feeling that a record in thrall to Francis Lai’s soundtrack to Un Homme Et Une Femme had no place on a label that was scoring big with King Crimson and Jethro Tull. Nirvana called in favours to get it finished; grateful for a loan to pay for production costs, they gave an extra-large credit to the son of one of Spyropoulos’s cousins on what was supposed to be a self-titled LP, leading it to be misnamed Dedicated To Markos III after it finally dribbled out in 1970. Not helped by an extremely weird-looking bones-and-fingers sleeve (“It looks like a bad advert for nail varnish,” says Campbell-Lyons), it was ill-suited to the golden age of Led Zeppelin, though “Excerpt From ‘The Blind & The Beautiful’” may be the greatest of Nirvana’s non-hits.

Musical returns decreased thereafter. Spyropoulos stepped aside, leaving Campbell-Lyons to bash together an unloved prog divorce album, Local Anaesthetic (almost redeemed by the lachrymose “Saddest Day Of My Life”), before Nirvana deactivated after 1972’s Songs Of Love And Praise. Key features: Las Vegas-friendly reworkings of “Rainbow Chaser” and “Pentecost Hotel”, plus grandstand finale “Stadium”, an oddball collision of Incredible String Band cosmic wonderment and Andy Williams production values.

Eternally hopeful, Campbell-Lyons kept chasing rainbows as Pica, Erehwon and Rock O’Doodle, among others, and even reunited with Spyropoulos in the 1970s to work on a vampire musical. The fleshed-out demos have emerged here for the first time as Secrets, with the Quadrophenia-worthy “Bingo Boy” and Abba fandango “Two Of A Kind” suitably quirky additions to the Nirvana canon. There was some West End interest for a while, but ultimately, Nirvana’s most tangible reward for their efforts came in the ’90s with “an amicable pay-off” from the Kurt Cobain Nirvana for having inadvertently stolen their name.

Their sound, though, remains very much their own. The contrast between Spyropoulos and Campbell-Lyons’ quavering voices and the skyscraping arrangements on Songlife makes for a camp mix of high art and showbiz; Keith West’s “Excerpt From A Teenage Opera” via Fellini’s 8½. Nirvana proved far too convoluted a proposition for the Saville Theatre audience in 1967, but their majestic softness makes complete sense in less alpha-male times. They were the plinky-plonk Pastels of their age – heavenly before Heavenly – a pre-decimal Vampire Weekend: a delirious, freaky flight of fancy.

Extras: 7/10. A big booklet thoroughly documents the Nirvana story, while those in search of non-album Nirvana material should head for Island’s 3CD Rainbow Chaser collection.