The Blue Note legend is not based on distinctive artwork alone. Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff, the company’s founders, cared enough about quality to pay for rehearsal time as well as putting the musicians in a good studio with a fine engineer. Yes, they presented the results in an attractive package with a coherent label identity. But they also paid scrupulous attention to what they included on their monthly schedule. Albums were selected for release according to how they would benefit the artists’ careers as well as the company.

They also recorded more than the label could release, which meant that when they effectively ceased their activities at the end of ’60s, there would be plenty left for archivists to discover.

Sometimes – as with the vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson’s Oblique – it was hard to work out why a session had not been deemed worthy of release at the time. Occasionally it was easier to understand: Grant Green’s Matador did not match the funkier direction in which the guitarist was heading; the tenor saxophonist Tina Brooks had faded into the shadows of addiction, which is why three of his five albums had to wait until after his death in 1974 to reach his small but devoted following. Someone with Brooks’ needs would have been particularly grateful for the label’s practice of recording so frequently, since Lion and Wolff paid by the session.

The principal reason the session Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers recorded in a single day in March 1959 remained unreleased for more than 60 years is obvious. Five weeks later, the same lineup recorded live at Birdland in New York City. Blakey’s bands always responded well to being taped on stage, as the three 10-inch volumes of A Night at Birdland had proved in 1954. Or perhaps it was Blakey himself whose reaction was key: his backbeats slammed harder and his press-rolls mushroomed more extravagantly in front of an audience, spurring his sidemen to new heights.

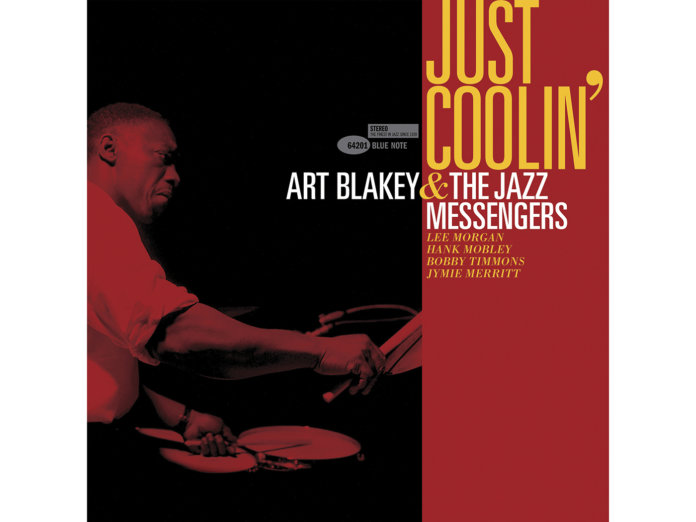

By comparison with the two volumes of At The Jazz Corner Of The World, as the Birdland recordings were titled when they were released to great acclaim later in 1959, the session now released as Just Coolin’ seems like a dry run, particularly since it wasn’t given a title or a catalogue number at the time. Of its six compositions, four appeared on the live albums, so direct comparisons are possible. The Messengers’ lineup changed frequently, for a variety of reasons, but it was a priceless graduate school for musicians from Clifford Brown to Wynton Marsalis, and Blakey always encouraged his players to bring along their own compositions. Immediately before the Just Coolin’ lineup came together, Benny Golson and Bobby Timmons had filled the repertoire with catchy items like the funky “Blues March” and the gospelly “Moanin’”. Immediately after, in would come Wayne Shorter, with more complex and unorthodox pieces like “Lester Left Town” and “Children Of The Night”. But this, in the spring of 1959, was an interim group, with Hank Mobley, a member of an earlier lineup, drafted back in to replace Golson and contributing three of his neat hard-bop tunes.

Welcoming the audience at Birdland in April, Blakey told them, “If you feel like patting your feet, pat your feet. If you feel like clapping your hands, clap your hands. And if you feel like taking off your shoes, take off your shoes. We are here to have a ball.” That’s not an easy mood to recreate in a studio, with only a handful of technicians for an audience, and although the band can still swing like mad, as they show on the up-tempo “Jimerick” (the only track whose composer remains unknown) and Mobley’s exuberant “M&M Blues”, inevitably Just Coolin’ has a more restrained air. Just as naturally, the intervening weeks have seen the compositions and arrangements evolve in different ways. Mobley’s “Hipsippy Blues” is slightly faster and crisper in the studio than the more relaxed and expansive subsequent live version, while the modal intro to the standard “Close Your Eyes” benefits in its later treatment from a nifty passage of cross-rhythms.

That’s not to say the studio session – one of the last to be recorded in engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s original studio, set up in his parents’ house – is substandard. Any chance to hear more of the extraordinary Lee Morgan is welcome; at the time he seemed the equal of his contemporaries (and fellow Blue Note stars) Freddie Hubbard and Donald Byrd, but the decades have set his brilliant and apparently inexhaustible imagination apart. Mobley, too, is someone whose laconic style never overstayed its welcome, although his occasional reed-squeaks might have given the producer a problem, had the session been considered for immediate release.

So you could say that it all turned out for the best. At The Jazz Corner Of The World will always remain a classic of live jazz recording, to which Just Coolin’ – released in a sleeve approximating Reid Miles’s original Blue Note designs – provides something more than a footnote.