A dark chronicle of his life and works... For all that Gene Clark’s story is as peculiar as its wilful, idiosyncratic and volatile subject, it is also one of the most trodden trajectories in modern popular mythology. “Take a group of young men,” sighs one of Clark’s collaborators, David Crosby, “give them some money, introduce them to drugs… I don’t think there was anything wrong with the fact that we all of a sudden got laid a lot. But the money and the drugs. . . that’ll do it every time.” The Byrd Who Flew Alone is subtitled “The Triumphs And Tragedy Of Gene Clark”. It’s a straightforward chronicling of Clark’s life and his works, which never quite permits itself to become a celebration of his extraordinary and resonant gifts. This is partly because of an implicit suggestion that maybe the determinedly diffident Clark could or should have done (or at least sold) more, mostly because everyone knows how this particular cautionary fable ends: dead at 46, killed by a bleeding ulcer engendered by decades of drink and drugs, topped terminally up via the windfall generated by Tom Petty covering one of his oldest songs (“I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better”, an irony about as leaden as they come). We’re told how Clark grew up poor, raised along with 12 siblings on the outskirts of Kansas City in a house without indoor plumbing. He was famous before he was out of his teens, recruited from his high school rock band by The New Christy Minstrels. He wearied, not unreasonably, of the Minstrels’ wholesome folk (in the archive footage of this period, Clark is conspicuously awkward in a suit and side-parting). Arriving in Los Angeles in 1964, he wandered into The Troubadour and saw Roger McGuinn playing American folk tunes rearranged in somewhat Beatlesesque fashion. Clark joined The Byrds. He was a megastar before he was 21. As The Byrd Who Flew Alone tells it, Clark spent his remaining 26 years struggling, with infrequent success, to reconcile an internal riot of contradictory instincts as he proceeded, as McGuinn recalls it, “From innocent country boy to road weary and just tired of it all”. Clark was at once a purist artist and a swaggering rock star. He craved pastoral simplicity, yet spent his money on Porsches and Ferraris. He never appeared happier than when playing music, but hated touring. He treasured the independence his success paid for, but paid little attention to his finances. He wanted to be left alone, but missed the applause when it wasn’t there. He was neither the first nor the last to attempt to drink, smoke, snort and shoot his way through these contradictions. Everyone who knew him speaks of him with a kind of affectionate sorrow. Yet the music that interrupts the rueful testimonies of family, friends and colleagues sounds nothing like failure. Though The Byrd Who Flew Alone does a serviceable job of relating Clark’s biography, it is difficult not to wish it dwelt a little less on how Clark screwed his health and life up, and a little more on the astonishing music he created despite the best efforts of his legion demons. The film – correctly – brackets Clark alongside the even more wretchedly self-destructive Gram Parsons as a godfather of modern Americana, but seems generally more intent on wringing its hands than applauding. In fairness, this is probably only to be expected when so many of the talking heads – including Clark’s wife, his kids, a brother and a sister, Crosby, McGuinn and Chris Hillman – are recalling first and foremost a husband, father, sibling or friend, rather than a musician. For those of us who weren’t obliged to worry about what his work was costing him, the niggling subtext to the effect that Clark under-achieved is risible. He was the principal songwriter on The Byrds’ first two albums. The solo records he made in the late 60s – one with the Gosdin Brothers, two with bluegrass maestro Doug Dillard – are pretty much the lodestone of country rock, for better (The Byrds, in cahoots with Parsons, finally caught up with Clark on Sweetheart Of The Rodeo) and for worse (Bernie Leadon, who played bass on the Dillard albums, later joined The Eagles, and took “Train Leaves Here This Morning With Him”). His 1974 album, No Other, is rightly described here by Sid Griffin as a classic. And the songs breathe still: Robert Plant and Alison Krauss’s 2007 stunner Raising Sand contained two Clark compositions. It is indisputably sad and outrageous that Clark’s name is not better known, but such is the fate of pathfinders in all fields: the ground they clear, often at considerable risk, ends up profitably settled by the meeker spirits who follow them. The Byrd Who Flew Alone is a richly merited monument, if one less succinct than Clark’s actual monument, a simple gravestone in his birthplace of Tipton, Missouri, which reads “Harold Eugene Clark: No Other.” Indeed. Andrew Mueller

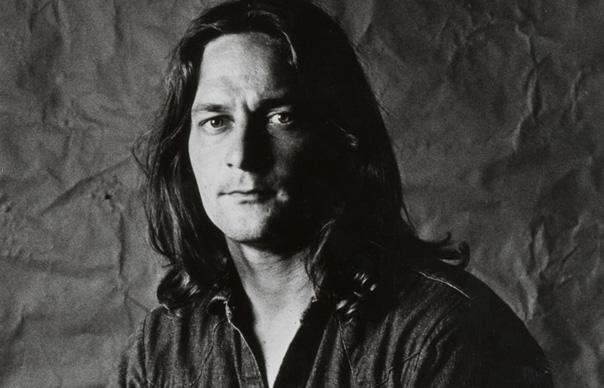

A dark chronicle of his life and works…

For all that Gene Clark’s story is as peculiar as its wilful, idiosyncratic and volatile subject, it is also one of the most trodden trajectories in modern popular mythology. “Take a group of young men,” sighs one of Clark’s collaborators, David Crosby, “give them some money, introduce them to drugs… I don’t think there was anything wrong with the fact that we all of a sudden got laid a lot. But the money and the drugs. . . that’ll do it every time.”

The Byrd Who Flew Alone is subtitled “The Triumphs And Tragedy Of Gene Clark”. It’s a straightforward chronicling of Clark’s life and his works, which never quite permits itself to become a celebration of his extraordinary and resonant gifts. This is partly because of an implicit suggestion that maybe the determinedly diffident Clark could or should have done (or at least sold) more, mostly because everyone knows how this particular cautionary fable ends: dead at 46, killed by a bleeding ulcer engendered by decades of drink and drugs, topped terminally up via the windfall generated by Tom Petty covering one of his oldest songs (“I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better”, an irony about as leaden as they come).

We’re told how Clark grew up poor, raised along with 12 siblings on the outskirts of Kansas City in a house without indoor plumbing. He was famous before he was out of his teens, recruited from his high school rock band by The New Christy Minstrels. He wearied, not unreasonably, of the Minstrels’ wholesome folk (in the archive footage of this period, Clark is conspicuously awkward in a suit and side-parting). Arriving in Los Angeles in 1964, he wandered into The Troubadour and saw Roger McGuinn playing American folk tunes rearranged in somewhat Beatlesesque fashion. Clark joined The Byrds. He was a megastar before he was 21.

As The Byrd Who Flew Alone tells it, Clark spent his remaining 26 years struggling, with infrequent success, to reconcile an internal riot of contradictory instincts as he proceeded, as McGuinn recalls it, “From innocent country boy to road weary and just tired of it all”. Clark was at once a purist artist and a swaggering rock star. He craved pastoral simplicity, yet spent his money on Porsches and Ferraris. He never appeared happier than when playing music, but hated touring. He treasured the independence his success paid for, but paid little attention to his finances. He wanted to be left alone, but missed the applause when it wasn’t there. He was neither the first nor the last to attempt to drink, smoke, snort and shoot his way through these contradictions. Everyone who knew him speaks of him with a kind of affectionate sorrow.

Yet the music that interrupts the rueful testimonies of family, friends and colleagues sounds nothing like failure. Though The Byrd Who Flew Alone does a serviceable job of relating Clark’s biography, it is difficult not to wish it dwelt a little less on how Clark screwed his health and life up, and a little more on the astonishing music he created despite the best efforts of his legion demons. The film – correctly – brackets Clark alongside the even more wretchedly self-destructive Gram Parsons as a godfather of modern Americana, but seems generally more intent on wringing its hands than applauding. In fairness, this is probably only to be expected when so many of the talking heads – including Clark’s wife, his kids, a brother and a sister, Crosby, McGuinn and Chris Hillman – are recalling first and foremost a husband, father, sibling or friend, rather than a musician.

For those of us who weren’t obliged to worry about what his work was costing him, the niggling subtext to the effect that Clark under-achieved is risible. He was the principal songwriter on The Byrds’ first two albums. The solo records he made in the late 60s – one with the Gosdin Brothers, two with bluegrass maestro Doug Dillard – are pretty much the lodestone of country rock, for better (The Byrds, in cahoots with Parsons, finally caught up with Clark on Sweetheart Of The Rodeo) and for worse (Bernie Leadon, who played bass on the Dillard albums, later joined The Eagles, and took “Train Leaves Here This Morning With Him”). His 1974 album, No Other, is rightly described here by Sid Griffin as a classic. And the songs breathe still: Robert Plant and Alison Krauss’s 2007 stunner Raising Sand contained two Clark compositions.

It is indisputably sad and outrageous that Clark’s name is not better known, but such is the fate of pathfinders in all fields: the ground they clear, often at considerable risk, ends up profitably settled by the meeker spirits who follow them. The Byrd Who Flew Alone is a richly merited monument, if one less succinct than Clark’s actual monument, a simple gravestone in his birthplace of Tipton, Missouri, which reads “Harold Eugene Clark: No Other.” Indeed.

Andrew Mueller