Jimi Hendrix only ever released three studio LPs under his own name during his lifetime, but in the 48 years since his death more than a dozen posthumous albums of material have been packaged from the hours and hours of tape that exist from his studio sessions – not to mention at least well over two dozen live collections.

The ructions over his catalogue are worthy of their own specialist biography. The first three posthumous LPs – The Cry Of Love, Rainbow Bridge and War Heroes – feature tracks that were salvaged from the vaults by longtime Hendrix producer/engineer Eddie Kramer and completed with minimal overdubs. The next batch – Crash Landing, Midnight Lightning and Nine To The Universe – were the result of jazz producer Alan Douglas controversially wiping musicians from the original sessions and replacing them with contemporary session players.

When the Hendrix estate, overseen by Jimi’s younger sister Janie, wrested control of the catalogue in the mid-1990s, they authorised two more MCA compilations of odds and ends overseen by Douglas – Blues and Voodoo Soup – and later enlisted Kramer to rescue some of the tracks previously overdubbed by Douglas to create the compilations First Rays Of The New Rising Sun and South Southern Delta (both released 1997). Ownership of the catalogue transferred to Sony in 2009 and Janie Hendrix again drafted in Kramer – alongside fellow producer John McDermott – to oversee one last trawl through the unreleased archive.

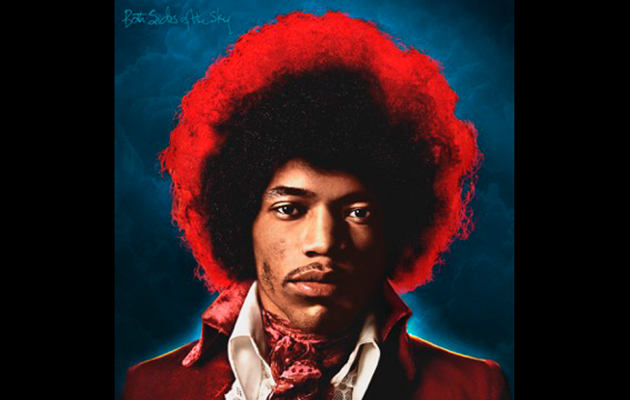

This trilogy of releases started with 2010’s Valleys Of Neptune, which concentrated largely on early 1969 material recorded in New York with the Experience – bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell – while 2013’s People, Hell And Angels largely focused on mid-1969 material recorded with his New York trio the Band Of Gypsys, featuring bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles. All of this brings us to Both Sides Of The Sky, the third in this trilogy. It features material mainly recorded in late 1969 and early 1970 with Cox and Miles, but also assembles a variety of sessions recorded in New York with assorted friends and associates.

Any investigation into the two, long, albumless years between Electric Ladyland’s release in October 1968 and Hendrix’s death in September 1970 will inevitably lead to comparisons between the Experience and Band Of Gypsys. To these ears, the Experience win hands down – in particular, Mitch Mitchell’s weightless, polyrhythmic style made him the only rock drummer who could really keep up with Hendrix’s freeform explorations – the Elvin Jones to Jimi’s Coltrane.

Still, the solid and unyielding funk-rock of Cox and Miles could also be effective, particularly on the high-pressure blues that Hendrix explores for much of Both Sides Of The Sky. Instead of racing fractionally ahead of the beat as he did with the Experience, here Hendrix plays slightly behind his rock-solid rhythm section, adding a sense of self-assurance to these 1969 sessions. Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy” is played with a funky strut and a Motown beat that transforms the Civil Rights implications of the Muddy Waters original (I’m a man, not a boy) into a sexual prowl (“Now I’m a man, age of 21, I have a whole lotta fun”).

Another blues standard, “Lover Man”, is turned into a weaponised piece of funk, with Buddy Miles in particularly thunderous form (and a great guitar solo – where Hendrix segues into the “Flight Of The Bumblebee” on the Live At Atlanta version, here he goes into the Batman theme around the 1:40 mark). Best of all is “Power Of Soul”, the kind of dense, airless, viscous groove where you can almost feel the sweat dripping from the speakers. You can see why Miles Davis, for one, seemed to spend the rest of his life looking to emulate this kind of funk.

Other tracks with Buddy Miles, however, compare unfavourably to those recorded with Mitchell. “Stepping Stone”, recorded in November 1969, sees Miles lurching from military tattoo to a galloping rockabilly, in a version that’s more thuggish than the funky, swinging, polyrhythmic version with Mitch Mitchell recorded two months later. “Jungle” is a rather pointless and fragmentary funk jam recorded with just Hendrix and Buddy Miles. “Send My Love To Linda” is Hendrix’s tribute to Linda Keith (the girlfriend of Keith Richards who, in 1966, saw Hendrix in a New York club and introduced him to Chas Chandler): the first two-and-a-half minutes see Hendrix singing and playing solo, before the band kick in with a surprisingly heavy proto-metal groove.

Ironically, the one track on this album featuring the complete Experience – recorded in April 1969 – shows that they are even better than the Gypsys at the kind of straight-ahead backbeat. Hendrix’s umpteenth version of the old blues standard “Hear My Train A Comin’” sees Redding and Mitchell in April 1969 beating out a slow, steady sludge-rock backing, with Mitchell starting out sounding more like Black Sabbath’s Bill Ward than Art Blakey. As Hendrix starts to burn around the two-minute mark, Mitchell’s drums take on that airborne quality, serving as Jimi’s wingman as they start to explore the outer reaches of space together.

Mitchell also appears in two duets with Hendrix. “Sweet Angel”, the only track on this album recorded in London, is an instrumental demo for “Angel” that sees Hendrix multi-tasking on guitar, bass and vibraphone while Mitchell flails away entertainingly on the drumkit. The other is “Cherokee Mist”, a rare invocation of Hendrix’s Native American ancestry and by far the best incarnation of a song that has only been available in various unsatisfactory forms for many years. Mitchell lays down a tribal tom-tom pulse while Hendrix doubles up on electric sitar and an ecstatically distorted guitar that sounds like a Theremin.

Other tracks see Hendrix jamming with pals he’d picked up in New York. Stephen Stills shows up twice to sing and play organ: first on a previously unknown song of his called “$20 Fine” (with Hendrix doubling up on guitar and bass, Mitchell on drums and Duane Hitchings on piano); and again on a swaggering, Stones-inspired version of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock”, featuring Buddy Miles on drums and Hendrix on bass. The arrangement clearly influenced the Crosby Stills Nash & Young version that was recorded a few months later, particularly Hendrix’s wayward but funky bassline.

Other old friends drop by the studio. Lonnie Youngblood, the soulful lead singer of Hendrix’s old band Curtis Knight & The Squires, turns up with his old bandmates to record the slick and efficient “Georgia Blues”; while Johnny Winter plays guitar on a 12-bar blues in 6/8 by Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones entitled “Things I Used To Do”, with Billy Cox on bass, Dallas Taylor from CSN on drums, and Hendrix singing lead vocals and trading solos with Winter.

This is supposed to be the end of a mammoth trawl through the archive, which still leaves many questions unanswered. Why did Hendrix ditch drummer Buddy Miles and go back to Mitch Mitchell? Had he had enough of Band Of Gypsys and concluded that this strain of the blues was a creative dead end? Moreover, there still isn’t any hint of the semi-mythological concept albums that Hendrix is believed to have been working on in those final two years – First Rays Of The New Rising Sun (as distinct from the 1997 comp of the same name) and Black Gold (the real Holy Grail for Hendrix fans). One gets the impression there could well be more goodies left in the Hendrix archive.

Like us on Facebook to keep up to date with the latest news from Uncut

Uncut: the past, present and future of great music