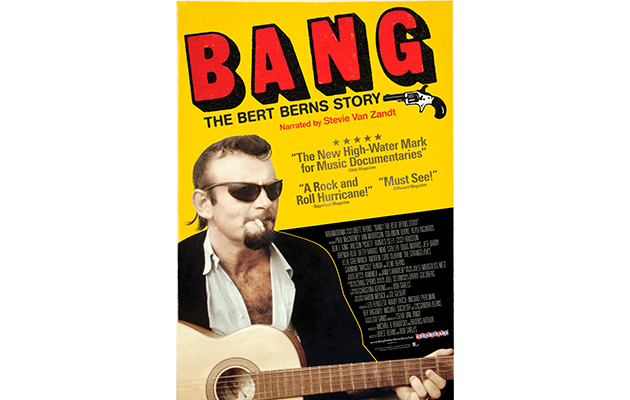

Bert Berns was a triple threat: writer, producer and, according to Exciters singer Brenda Reid, “white soul brother”. A swaggering, charismatic Bronx boy who wrote dozens of classics – “Piece Of My Heart”, “Under The Boardwalk”, “Here Comes The Night” and “Twist And Shout” among them – Berns was “one of the greatest songwriters of all bloody time”, according to Keith Richards, one of several stellar interviewees in a film narrated, with full Noo Yawk brio, by Stevie Van Zandt.

It’s a colourful tale, mostly pieced together by wiseacre Brill Building types talking out of the sides of their mouths. Mobsters pepper the narrative and tall tales abound. When 35-year-old Berns marries Ilena, a “22-year-old Jewish go-go dancer”, his mother warns him her youthful beauty will prove fatal to a heart weakened by a childhood bout of rheumatic fever. Aware that his time on earth was likely to be limited, Berns lived life to the full, but an underlying sadness played out in his songs. They were “complex and neurotic” pieces, says his biographer, “masquerading as teenage records”.

His love of Cuba – he claimed to have run guns and drugs for the revolution – can be heard in his early hits for Atlantic, including Solomon Burke’s “Cry To Me” and The Exciters’ “Tell Him”, which introduced Afro-Cuban rhythms to rock’n’roll and R&B. After The Beatles covered “Twist And Shout” and The Rolling Stones recorded “Everybody Needs Somebody To Love”, Berns travelled to London to scout talent, working briefly with Them. Van Morrison pops up in Ray-Bans and Barbour jacket, in unusually gracious form. “The guy was a genius,” he says. “A brilliant songwriter with a lot of soul.”

Later, Berns formed BANG! Records and made “Brown Eyed Girl” with Morrison, as well as launching the career of Neil Diamond. By now, he has “money coming out the yin-yang” and is bosom buddies with Tommy Eboli, head of the Genovese crime family, “a knee-buster and leg-breaker of the first order”. When things go awry, Diamond is threatened and his manager mugged. Morrison goes through similar torture. A spectacular feud with Jerry Wexler, Berns’ mentor and business partner, ends with GoodFellas levels of intimidation. His desk is loaded with pill bottles and a revolver, and “he seemed stressed all the time” – which coming from Van Morrison is saying something.

Berns’ fragile heart finally failed on December 30, 1967, aged 38. “I don’t know where he’s buried, but if I did I’d piss on his grave,” was Wexler’s eulogy. This vibrant film – while acknowledging the dark stuff – offers a more generous assessment of a man who, says Paul McCartney, “deserves to be elevated to his rightful place”.