One of the many frustrations of Donald Fagen’s memoir, Eminent Hipsters, is a general absence of Walter Becker. Fagen writes elegantly, eruditely, about growing up in a time of Henry Mancini and the Red Peril; about jazz DJ epiphanies under the bedcovers, and a mortifying attempt to interview Ennio Morricone. The man with whom Fagen co-authored some of the greatest records of the past 50 years, however, remains tantalisingly elusive.

He arrives in a chapter notionally about Fagen’s time at Bard College. They start making music together: “The sensibility of the lyrics, which seemed to fall somewhere between Tom Lehrer and Pale Fire,” writes Fagen, “really cracked us up.” Chevy Chase is briefly their drummer, keeps “excellent time”, and “didn’t embarrass us by taking off his clothes.” It being the late ‘60s, drugs are involved. A droll yarn results in Fagen “looking like an accident involving a giant crow and an electric fan.”

Becker, however, takes up roughly two and a half pages, then is gone: “But that’s another story,” notes Fagen, unnecessarily, and it’s one he’s clearly unwilling to tell. We have reached page 86, about halfway through Eminent Hipsters, and the point where the meaty tale of Steely Dan should be belatedly getting under way. Fagen, though, is interested in a different story – a grouchy tour diary about a recent solo road trip – and a substantially less complicated one.

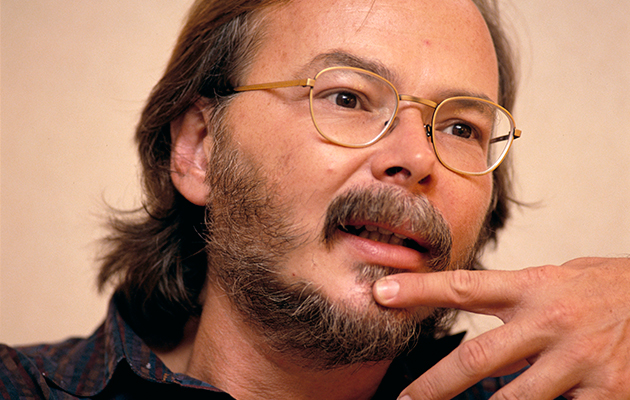

What do we know about Walter Becker, beyond the snark and the fragments of ancient gossip? An exacting perfectionist. A coruscating wit. A hack composer called Gus Mahler. A masterful guitarist who would usually cede responsibilities to a battalion of other guitarists (the funniest thing I saw on a sad day was a tweet from the American music critic Brad Shoup, who wrote, “To properly honor Walter Becker, your editor is auditioning 15 freelance eulogists.”). In an unusually personal piece from Rolling Stone in 2000, the writer Alec Wilkinson quotes a friend of Becker’s: “Walter has a kind of ring around him, an aura, that suggests that if you fucked with him he would go to the ends of the earth to get even. This has been very good for Steely Dan. It scares the businessmen.” In the same piece – arranged to coincide with the severely undervalued reunion album, Two Against Nature – Becker briefly describes the substance issues that once plagued him as “social ills”.

It is hard, browsing through the accumulated interviews with Becker, to find much he says that couldn’t be usefully described as droll. In a classic Michael Watts Melody Maker piece from 1976, Becker admits that, “It may be right in saying that the world crystallised through our eyes bears very little resemblance to anyone else’s world, even though we think we’re recording it as we see it. We may be so bent that it’s unrecognisable. I would like to think so. That would certainly make it more interesting.”

Such a withering, “bent” eye might not always be appealing, just as a guiding principle of irony can have its limits. Earlier this morning, I had an email exchange with my wife about her abiding suspicion of Becker, Steely Dan and their music. Smugness was mentioned – as usual, pejoratively. But for Becker and Fagen, a kind of smugness was positively weaponised. Their collected work, in a certain light, reads something like a metatextural critique of smugness, written by smug dudes acutely, neurotically aware of their own smugness. If you’re built that way, you might as well find a way to make the most of it.

In that same 1976 interview, Becker – who always sounded amusingly disappointed by humanity, with a tone of aged and weary sagacity that he appeared to have had adopted around adolescence – lamented that kids today didn’t share their literary values, their scholarship. And his creative voice, his wry aesthetic, had a potency for those of us who wanted their nerdiness to be transformed into aggressive hip. Too often, we probably fell short of Becker’s meticulous wit, as the tone curdled into mere sarcasm.

But Becker and Steely Dan’s terrible secret was a moral imperative: a desire that people – not least themselves – could be better. Their satires were rooted in a sadness that the world wasn’t a smarter place and, if they weren’t quite so brilliant to work out how it could be improved, at least they could compensate by making it sound perfect. The contrast between the gleaming surfaces of Steely Dan’s records and the terrible flaws exposed by their lyrics sounds less, these days, like a delicious irony, and more like a chronic poignancy.

“I don’t think these are particularly cynical times,” Becker told Michael Watts in 1976. “You just wait to see what’s coming up! I’m inclined to think that things are going to become far more pessimistic.

“Of course, pessimism and cynicism are not the same thing at all. Cynicism, I contend, is the wailing of someone who believes that things are, or should be, or could be, much, much better than they are.”